By Martina E Faulkner

I always think it will get easier.

And I’m always wrong.

Every time.

It’s not easier over time, it’s more numb. Consistency and frequency only served to create an existential morphine-like balm to the frayed nerve endings of emotions swirling through my body and brain.

And now, when there are gaps in time, the nerves become more sensitive, just like withdrawal. Only, the solution is not more ‘heroin’… the solution is recognizing the inescapable truth that it doesn’t get better from here.

And even that, I’m afraid, is no solution at all.

I wrote those words yesterday as I sat in my car, throat choked up and dry cheeks. No tears would fall, even though they were there. They were dammed up inside me, bottle-necked… stuck. Trapped might be another word for it. My tears were trapped, just as I have been, as I have felt.

I’m trapped by duty.

I’m trapped by circumstance.

I’m trapped by fear.

I’m trapped by grief.

But mostly, I’m trapped by love.

Eleven and a half years ago my father had a horrifically debilitating stroke. He survived. I wish he hadn’t. Because he survived; he didn’t live. And while he’s been alive, he hasn’t been living.

I suppose it hasn’t always been like this. The first 3 – 4 years were full of hope, of promise. He beat seemingly unbeatable odds to regain some of his losses, things like: swallowing or speaking small phrases or words. Those were huge wins at the time. We gave him every opportunity to gain more. He had therapists and therapies, was part of research studies, and had the best caregivers we could find, in addition to us. We thought maybe, just maybe, he would walk again. Or talk again.

He never walked again.

He talked sometimes.

He spoke in sounds or single words, not sentences, combined together in phrases that often had little to do with what he was trying to convey. So, we learned. We learned how to change our own language to accommodate his. Gone were the open-ended questions that create conversation. They were replaced with simple questions with “yes” or “no” answers. And even then, he didn’t always get it right. Sometimes “yes” meant “no,” but rarely did “no” mean “yes.”

He spoke more with his eyes than his lips. I became fluent in eye-language. If the eyes are the windows to the soul, my father was writing epic tales with his. Except on the days when he wasn’t. The days when his eyes seemed vacant and almost infant-like. Just staring through me as I talked to him with the sense that little or nothing was registering in the catalogs of his mind.

Through it all, he was a constant, because he was trapped. Trapped in a chair, in a house, bound to a caregiver and a tightly planned schedule, all to keep him safe and offer him the best possibility for improvement. Only, he never improved. Not really.

Eventually, he began to decline the therapies – even his favorite one: horseback riding or Hippotherapy, as it’s called. He started saying no to any suggestions of something new, and his world became even smaller. And with his shrinking environment, our hope moved in response and began to subside. We now knew:

He wouldn’t get better.

He wouldn’t restore.

There would be no miracle.

Those miracle ‘chips’ were used up the day of the stroke by having him survive at all. His steady molasses-rate of decline was underway, and there was nothing we could do about it. Instead of hope, it simply became a matter of time, and a constant question of: When?

When would he pass?

When would this end?

When would there be relief?

When could we legitimately start to grieve?

Throughout the years, too many people felt it ‘helpful’ to remind us how lucky we were that he was there at all – suggesting at times that we should celebrate every day. And yet, none of them seemed to know what it was like to wake up each morning and experience the grief of loss, every day, without the person being dead. It was thousands of deaths, and no dying. So, grieving has mostly been put on a back burner, until the day when it will all come pouring forth. The day when there’s a body to be buried, instead of the daily lamenting of the loss of a dad.

Of course, it wasn’t all depressing. We have embraced the “luck” of his survival. There were many celebrations and beautiful moments and highlights throughout the decade. Taking him Christmas shopping every year is one of my favorite memories. We would wander the mall searching for gifts for my mom that he got to pick out (with a little guidance from me), before having lunch in his favorite café where the Manager gave him hugs. If he hadn’t survived, I wouldn’t have those memories. I recognize that. I see it, and I am grateful for it. And then I’m sad.

Because even though there have been happy moments and good memories, that I and the rest of my family will cherish, they have not yet outweighed the constant, chronic, and daily decline that we have witnessed – no, experienced – over the last decade. Perhaps years from now when the grief has subsided and the relief has been realized, they will come to weigh more than they do today. I hope they will. But today, they don’t.

They don’t because I see a man who is crumbling. Slowly eroding away like the castle walls of an abandoned stone fortress facing the wind. He was a tower of a man. His demise is not something you notice every day; but month over month and year over year, the destruction becomes evident. He is deteriorating before our eyes, and there is nothing we can do about it. The most we are capable of doing is bringing little moments of joy to his otherwise reclusive days.

Like yesterday.

Yesterday, before I wrote those words, I visited him at his care home where has been living for about seven months, after we could no longer safely provide for him at home. I go once a week. It used to be more, but I can’t. Perhaps that sounds selfish. I can’t go, because it takes days for me to recover once I’ve been there. Some weeks I’ve gotten it down to a day of recovery. Some weeks it’s taken three. And for various reasons, there have been weeks when I haven’t gone at all. Those weeks have been happy for me. Or happier.

Happier because I don’t have to be reminded of the sorrow and helplessness I feel looking at my father trapped in his chair, his body, and his mind. Happier because I am not trapped by the obligation I feel to visit him.

It’s my choice, of course. I know that. And it’s a choice I make willingly, perhaps to my detriment some days. But, like the memories of Christmas shopping, I have hope that my choices will one day come to outweigh the despair they cause today.

Watching my father neither live nor die, yet slowly decline towards death for over a decade has been a privilege and a burden, the likes of which I never could have known. And on more than one occasion it has nearly broken me. On more than one occasion I have asked – begged – for him to die.

It used to be an intermittent request, but lately, it’s become my norm. For him, he’s been saying “I want to go home” regularly for over six years. For him, “home” is Heaven. For him, going home is freedom. For me, his “going home” is peace.

In all my life I never thought I would ever be able to say those words, let alone have those feelings, and yet… I now feel them every week. Every week while I feel grateful to hug him once more, I am also asking God, or the Universe, or whomever will listen, to please, please take my father home. Please end this.

And yet he’s still here.

He’s still here sitting in his chair, trapped in his body and his brain, going through the paces of his daily life, without actually living most of it. Just as I feel trapped here, going through the paces of my own life with aging parents, not fully living myself. It’s funny how the one mirrors the other. And it won’t change until it does.

I can’t change it. I’ve tried. It doesn’t work. It is a level of acceptance that goes beyond anything I had previously known, or ever want to experience again.

I accept that my dad is not living.

I accept that my dad is not dying.

And I accept that I have chosen to be a part of this process.

So, I go. I do my duty as a daughter and a human being, and I go. I spend time with him. I make memories that will stay with me, but he can no longer contain. I go, because it’s the right thing to do. And I go, because there is nothing else I can do.

I go out of obligation, out of sympathy… and, mostly, out of love.

I go because somewhere inside me I have to believe that today’s pain will turn into tomorrow’s gratitude and joy. And so, I sit and hold his hand, share a meal and some stories. I laugh, and I do my best to bring joy to his ever-shrinking world, hoping that it will conversely bring expansion to my own.

And all the while I smile through tears that won’t come.

Martina E. Faulkner, LMSW is an Author and Certified Life Coach whose work explores the merging of the human and the divine by helping others to reconnect with who they are and live from that place. In her writing, Martina focuses on creating small shifts in perspective that inspire hope, change, and possibility – making ideas both accessible and actionable. This combination results in a more empowered and authentic life experience. Martina can be found online at www.martinaefaulkner.com and www.inspirebytes.com.

Donate to the Aleksander Fund today. Click the photo read about Julia, who lost her baby, and what the fund is.

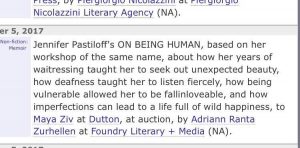

Join Jen at her On Being Human workshop in upcoming cities such as NYC, Ojai, Tampa, Ft Worth and more by clicking here.

3 Comments

My dad is the same. Your words resonate ❤️

Thank you. <3 It's hard, isn't it? But worth it in the end, I hope, to be there – no matter how challenging.

Martina: Terrific piece. So moving. Your Dad was one of my best friends at GU. We both enjoyed each other and laughed a lot.

I might be able to visit him. Best to Mom .

Joe Priory.