by Nicole Bokat

While researching my new novel about a woman’s relationship with her stepsister, a wellness guru, I was surprised to find myself getting hooked on Happiness. All my life, I’d been a mix of self-effacing pessimist and tenacious worker, resilient in the face of defeat. Sheer will had pushed me to meet my goals. But, within the last decade, a career slowdown coincided with the grief I experienced over my sons leaving home. I was able to handle the rejection and the loneliness–just. I continued to persevere, although my dark moods and cynicism hung on longer than usual. Like Natalie, the heroine of my book, I needed to look on the bright side.

At the library, I plucked tomes off the shelves on flourishing, thriving in the “blue zones,” finding “flow,” stumbling onto, falling into, and consciously choosing to be gleeful. When I checked out one on ‘angel guides,’ I tucked it immediately into my backpack, as if hoarding spiritual porn. But, I persisted on my quest for well-being.

Until my husband fell ill.

When the urologist drew lines on the image of a plum-shaped prostate, with the besmirched areas, my anxiety peaked so high I could smell it. Coming from a family where cancer snaked through the male line, I worked hard not to be retraumatized. My uncles died young from lymphoma. On the eve of this new century, my 67-year-old father had received a carcinoma diagnosis that killed him in eight months. Death came for my father with a ferocity that yanked me upside down. Now, fifteen years later, I couldn’t lose my sense of gravity again.

I ditched the luxury of self-improvement and embraced survival for my spouse.

Thankfully, he recovered after receiving an ultrasound treatment that was hard to get in the United States at the time. The frequent bloodwork, scary MRIs, and follow up appointments have kept us vigilant. But five years have passed, and the disease hasn’t returned.

Then, during a routine physical, my EKG came back abnormal. I underwent a month-long prescription of cardio tests for a congenital defect that, somehow, had gone undetected until my fifties. While I was asymptomatic, my thickened heart wall might give me trouble in the future. Plus, my sons could have inherited my condition.

How, I wondered, could human beings—with all our fragility, our lurking mortality—find true joy? The work on my new novel proved fortuitous, a way to shake myself out of my existential slump. I was secretively hopeful —like Natalie—that I’d discover a recipe for a more hopeful, sunnier attitude.

Experts seemed to tell me I could, even in the face of multiple life challenges, be happier. Sonja Lyubomirsky, a UC Riverside professor, claimed our mindsets were malleable. That perked me up! According to her research, our “happiness set point” determines 50% of our mood, our intentional activity 40% and, circumstances only 10%. She wasn’t alone in endorsing the idea that I could tweak my temperament. A host of PhDs and MDs swore that our brain could be retrained away from its negativity bias. Mindfulness could alleviate tension. The message was that with grit, persistence and the right perspective, we could change our collective minds.

I was determined to implement the right techniques to be rosier. I eagerly purchased Professor Ben-Shahar’s book Happier, based on his class, the most popular course in Harvard’s history. Martin Seligman, the Director of the Positive Psychology Institute at University of Pennsylvania had much to say about Learned Optimism and The Circle of Hope. I downloaded the Happify app, created by participants with doctorates and medical degrees. Heeding these specialists’ advice, I scribbled into a gratitude journal, tried to savor the moment, and meditated to the mantra “OM.” Practicing religion or searching for the sacred was tougher. But I managed to murmur “Namaste” at the end of yoga class.

Two hundred TED Talks given by a bevy of doctors and therapists encouraged looking on the bright side. Yet, like Natalie, the more I tried to apply their techniques, the more frustrated I became. When I received professional rejections for my novel, I berated myself. Why couldn’t I enjoy the journey and not worry about the reward?

Like my fictional counterpart, I persisted in trying to change my negative thinking. But while I could tame anxiety, my cynicism prevailed.

One day, while listening to the advice of a successful executive coach, I had to admit the truth. For these experts, there was good reason to celebrate: they’re part of a nearly ten-billion-dollar audience for motivational self-help programs and products. But for the rest of us, searching for contentment often feels elusive.

So if self- help doesn’t always work, what does? Scientific American reported that one in six adults in the United States takes a psychiatric drug (as of 2016) and, according to the World Mental Health Consortium, we are the third most anxious bunch out of 26 countries. The Census bureau data found that symptoms of depressive disorder in Americans doubled from 25% to a whopping 50% since the pandemic. In the 2020 World Happiness Report, we ranked 18 out of 150. Not a bad number but way behind Nordic countries like Finland (#1), Denmark (#2), Iceland (#4) and Sweden (#7), where trust between citizens, safety, gender equality, equal distribution of income and less economic insecurity all contribute to collective satisfaction.

How could we get out of this muddle? Experts in the mental health field emphasize that the solution to despair can be found in several areas but that social connections and a sense of purpose are key. Engaging in activism — doing for others — can not only benefit the less fortunate, but gives one a sense of control.

I realized that bliss can’t be found from a blog, a webinar, an app, or a cleansing breath. Once Natalie has this revelation, she begins to make sense of life’s worst traumas by creating art through her photography, to take chances. I, too, needed to revise my work, to reimagine. While deep in the writing, I wasn’t thinking of health emergencies, or contentious politics or even the tragedy unraveling over the course of this life-shattering pandemic. Instead, I was lost in another world, a deeply satisfying one: my novel.

Nicole Bokat is the author of the novels The Happiness Thief, Redeeming Eve and What Matters Most. Redeeming Eve was nominated for both the Hemingway Foundation/PEN award and the Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize for Fiction. She’s also published The Novels of Margaret Drabble: “this Freudian family nexus,” She received her PhD from New York University and has taught at NYU, Hunter College, and The New School. Her essays and articles have appeared in the New York Times, Parents magazine, The Forward, and More.com. She lives with her husband in NJ and has two grown sons. Find her online at her website, Facebook, or Instagram.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Margaret Attwood swooned over The Child Finder and The Butterfly Girl, but Enchanted is the novel that we keep going back to. The world of Enchanted is magical, mysterious, and perilous. The place itself is an old stone prison and the story is raw and beautiful. We are big fans of Rene Denfeld. Her advocacy and her creativity are inspiring. Check out our Rene Denfeld Archive.

Order the book from Amazon or Bookshop.org

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

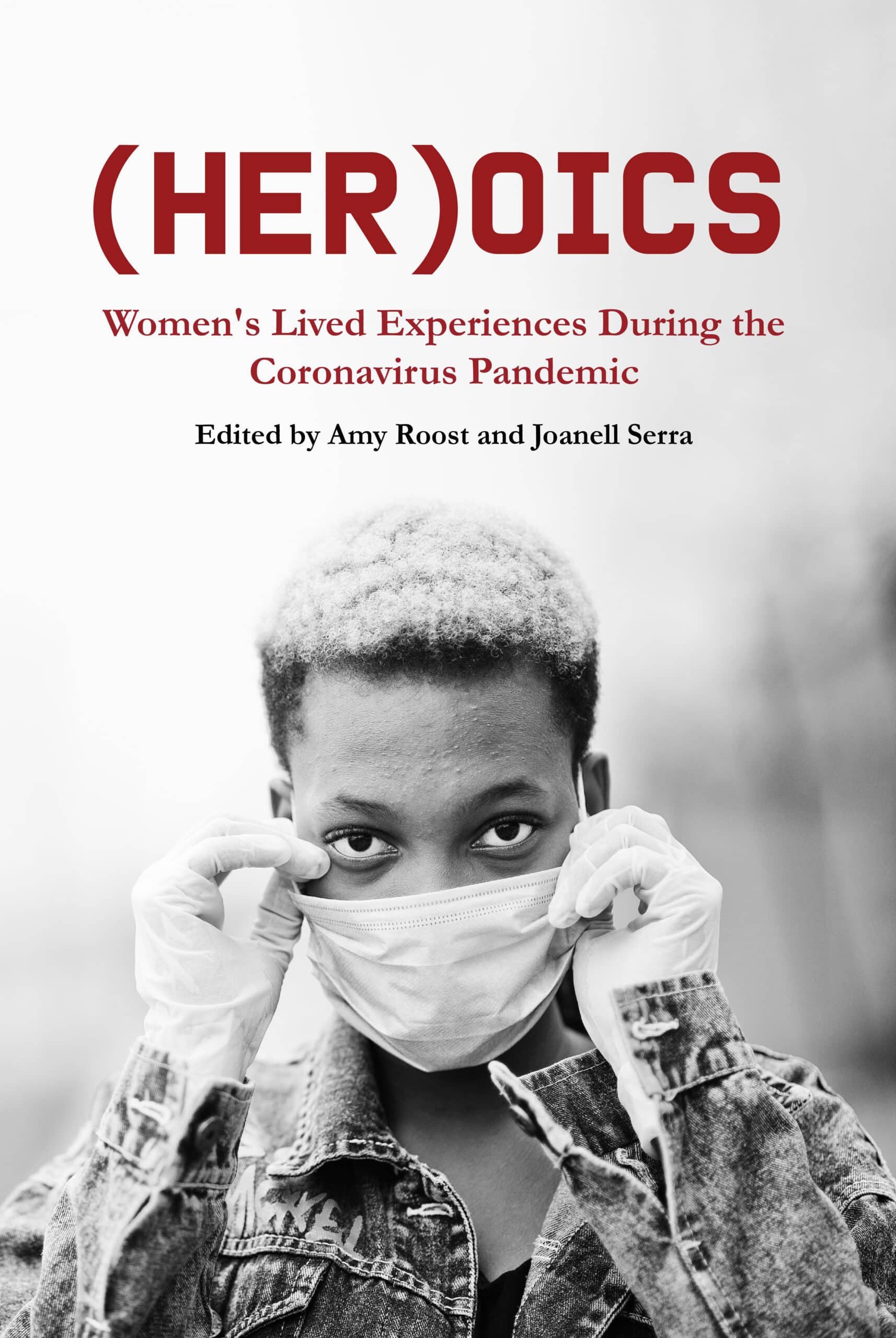

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~