Note from Founder Jen Pastiloff: This is part of my new series called No Bullshit Motherhood. Raw, real, 100% bullshit free. If you have something to submit click the submissions tab at the top. You can follow us online at @NoBullshitMotherhood on Instagram and @NoBSMotherhood on Twitter. Search #NoBullshitMotherhood online for more.

By Chris J. Rice

My ten-year-old son stood beside his father in the front yard of my now empty house. My son had a scowl on his face. Looked away from my packed car, down at the ground.

Dark-eyed boy with a skeptical furrowed brow.

“Come here,” I said. Called him over to my driver-side window.

He stuck his head in for a kiss, and I whispered in his ear: “You’re going to miss me. And that’s okay. It’s okay to have a dream. Never forget that.”

He nodded as if he understood. “Bye,” he said, then turned around and ran back to stand with his father.

I put my Datsun in reverse and took off. Moved to Los Angeles to attend graduate school. And I didn’t take my child along. I left him with his dad for the duration. I told them both it would only be a few years, though I knew it would be more.

I sensed it would be forever.

A formal acceptance letter came in the mail and I made a decision. Put my books in the post, my paint box in the trunk of my yellow Datsun B210, and drove headlong into whatever came next. Sold most of my stuff in a big yard sale: the vintage clothes I thought I’d never wear again, the leather couch and chair I’d bought dirt cheap off a moving neighbor.

I didn’t have much left after the divorce.

I said it. My ex said it too. I love you. But he didn’t mean it. And for the longest time I didn’t get that. Just picked up the slack. Made things happen. That’s how it was. Okay. Just okay. He would get angry. Couldn’t seem to manage. Fury popped up like every other emotion. Yelling. Disparaging—things like that.

I missed my son like mad. We talked by phone regularly. I flew back on holidays. He came to visit on spring break, and for a few weeks every summer.

Seven years passed.

My best friend Mark died of AIDS, and my now seventeen-year-old son flew in to Los Angeles from Oklahoma City to attend the memorial service. Said he’d never forgive himself if he missed saying good-bye. They were buds, my kid and my dearest friend, an instant match from the moment they met, both of them physical comics preferring to communicate in quirky one-liners and body pranks.

Generous beyond sense, my friend Mark, a thin bony elegant man; a bright, funny magical man: a hilarious man. Once he picked me up from the airport wearing an oversized rabbit head. Sat in a chair by the gate and waited for my arrival with that head on.

He saw the seams in things. The way life was merely stitched together. Held together lightly. A jostle, a swerve and it all fell apart.

The memorial was held in Pasadena, the swanky section, in an Episcopal church known for political activism. The architecture was elaborate: outside all soaring Gothic revival, inside heavy wrought iron sconces and chandeliers. Symbols of renewal and resurrection were carved into the pews and on the walls: thistles, pomegranates and acorns. The ceiling overhead was like the ribcage of a sleeping giant, oak beams protecting and oppressing.

My son sat beside me, grinding his teeth and rolling his program into a tight weapon. He looked around, not at the people in attendance, my friend’s shaken partner, his parents or close friends. No. My son checked out the grandeur of the cathedral. Nudged me and pointed to a gorgeous stained glass crucifixion on the opposite wall.

When my son was four, he found a crucifix in our attic, stored there by a family friend. “Who killed this man?” he yelled from above and ran down the stairs into my arms. Terrified. Alert. Haunted by what he had seen. Like me at that same age, shaken awake in a movie theatre watching a Cyclops in Jason and the Argonauts roast men alive and then eat them like chicken.

I jumped and ran too. But not into my mother’s arms.

I didn’t tell my son a religious story the day he discovered the crucifix in the attic. I showed him reproductions of paintings instead. Pulled H. W. Janson’s History of Art down off the bookshelf, and together we looked through centuries of body drama: painted and carved, sculpted and drawn, both of us transfixed by the horror, and the grandeur too. The shallow pictorial space, so close and packed with drama, the pillar of the cross, the agony of the man and the sorrow of the world below.

The images were powerful, both the northern and the southern versions.

After that my son kept the textbook with his other picture books, in his room on his toy shelf by the miniature dump trucks and the puzzles.

One afternoon on the way home from a play date, my son announced he had the death of Jesus figured out. “I know why those people did that to him,” he said.

“Why?” I asked, really wanting to know.

“He just kept talking and talking and he wouldn’t shut up so they killed him.”

I flipped through Mark’s memorial program, printed on tasteful off-white stock with a black and white photo of him on the cover holding a kitten. Taken on a trip he and his partner made to Marrakech. One of the many trips they made in the final years, so much to pack into the unknown time left, with art still to make and a legacy to leave. At the back of the program was information about an art scholarship in my friend’s name. Mourners were invited to a reception after the service, to be held at the house he had shared with his partner. There was a story Mark had written about his encounters in the woods, titled: Untitled 1991. As I read the last line: “I rejoice knowing that it’s still there and always will be and I am sweetly beckoned to come home,” the recessional began. “Solsbury Hill” by Peter Gabriel. We all stood up and filed out of the sanctuary, down the aisles and out to our cars.

Grab your things, I’ve come to take you home.

It was a beautiful day, not too hot. After the memorial service, all the close friends — and there were many — gathered in the house, a mansion in Hancock Park the size of an embassy. His favorite music was playing, female singer/songwriters: Joan Armatrading, Phranc, and Donner Summers. And several of us walked between the servants’ kitchen and the sunroom carrying refills of coffee, tea and fizzy water, sharing side-eyed commentary as if our sarcasm still included him: our funny friend who hadn’t been able to laugh for so long, too ill to be carefree, too medicated to smile.

My son put on headphones and disappeared as soon as we walked in the door.

I wandered from room to room, still expecting to find my friend around every corner. It was the first time I’d been back in the house since he had died there, in a bedroom upstairs. Now I saw him everywhere, especially in the art on the walls and the souvenirs on display, all of it gathered from exotic trips he’d taken during what would be his final years: penis sheaths from Papua New Guinea, Mexican Dia de los Muertos masks, Gaudi tiles from Barcelona, Moroccan crosses, and Chairman Mao pins from Hong Kong.

He believed in the power of art: to heal, to transform lives.

In art school Mark towered over everyone in talent, skill, wit, grace and humor, especially humor. Every time he looked at me, I smiled. I laughed. I looked back at him, confident and unashamed. He helped me see past my crippling self-doubt. Carried me with him into larger insights. With him alongside, I began to think maybe, just maybe it was okay to be me. He was a good friend, an even better artist, a sometimes clown, and an occasional cross dresser. One afternoon he surprised me with a shimmy across the parquet floors of the very house we would someday meet within to mourn. He lip-synched to a disco beat. Bounced in a floral jumpsuit. Wiggled his slender hips. Polyester swirling. Eyes shining. Me laughing. On the floor collapsed in breathless spasms.

Disarmed by his trust, his gender-bending dance, and his joy.

After all he had been through. All I had been through.

He was a storyteller too. Fascinated by the switchback of time, the circle of time, how a single life moved from now to then, and even further back: the weight of the generations alive in each and every one of us.

“He loved me very much, no matter what anyone says. He loved me!”

I entered the den, the room where my friend had danced that day, where we had spent so many hours together, in time to see Mark’s mother grab his grieving boyfriend R by the arm, and say loud enough for the entire house to hear: “He loved me!”

As she said those words, the bookshelf against the far wall fell. Hard. Books spilled all over the parquet floor. Alice Bob, the cat, scurried off. My friend’s boyfriend raced after the animal. No one bothered to pick up the books, or soothe the dead man’s distraught mother. All of his friends knew the story. How he’d hidden from her in closets, hallucinating with fear. How he’d moved across the country to get away.

I wondered where my son had gone and dashed off to look.

I found him alone in the backyard. Headphones still on, he tossed a basketball against the door of Mark’s studio. A space I hadn’t entered since before he had died. I was afraid to see it empty of him, and full of his now forever-unfinished art. Fragments of potential alongside the few things he had somehow managed to complete, first with his own hands, and then with the aid of loving assistants.

The last year of his life, he could only direct construction from the sidelines, his partner R paying for the space and the time and the helpers: a lover doing what he could.

“What’s with him?” R asked. Pointed toward my son who was now in the driveway. “He’s old enough to help but he hasn’t helped with anything.”

“He doesn’t know anybody here,” I explained.

And neither did I. Not really. Most of the guests were people I’d met since I moved to LA. Many I only knew through my dead friend and his lover. Their closest friends were my occasional friends –people I saw only once in a while, arty acquaintances who gathered to mark each other’s milestones and patronized each other’s work.

People like me, who show up when they are able.

When I left my son with his dad in Oklahoma and moved to L.A. for art school, I told my ex and my son what I told myself: I was just exchanging a few years of custody for career investment. After grad school I would be better equipped to help support my son. I wouldn’t be the drain on my ex that I’d been. I was so convincing, my ex ended up saying: “Oh, you never mind and of course. You go on and do what you need to do, we’ll be fine.”

We don’t need you is what I heard.

Our son doesn’t need you.

After I graduated, when the time came to move back to Oklahoma City, I stayed in Los Angeles. Even after I split with my boyfriend and had to downsize to a single, I stayed. Even after I lost my job, couldn’t pay my student loans, and had to file for bankruptcy, I stayed. By then I told myself I couldn’t leave my sick friend.

That was my excuse, but that was not the only reason.

I was twenty years old the first time I got pregnant. Never even thought to use birth control. The guy was a gorgeous American Indian artist taking drawing classes at the college I attended, waiting for his big break, a Smithsonian show that would travel through Europe. I liked him a lot and I trusted him to pull out like he said he would. By the time I discovered I was pregnant, he had moved on to another girl, and I was dating his best friend, a bearded guy ten years older than me, with broad shoulders, red hair and green eyes like Mama’s. The artist gave the bearded guy the money for my abortion at a Planned Parenthood in Dallas, Texas and then he disappeared.

The nurse used an anatomical model of a uterus to explain what they would do during my procedure, and I broke out in a cold sweat, shot up out of the metal folding chair and ran into the bathroom where I dry-heaved into the toilet.

I didn’t know whether I ever wanted to be a mother, if I ever wanted to have a child. It had only been two years since I’d transitioned out of foster care.

The doctor inserted a plastic tube into my uterus and said: “You look like an angel lying there.” I gripped the nurse’s hand and watched blood coil its way toward a high-hanging glass bottle, my pregnancy going away.

In recovery, I held a pillow against my empty stomach, hair wild and breasts still swollen. Found my dress and then the holes for my head and arms, zipped up, covered up, and prepared to go back into the world, bra straps cinched up tight.

Hair down to my waist, dressed in a muslin maxi-dress and knee-high squaw boots, Kotex between my legs, blastocyst gone, I grabbed my patchwork bag and went into the waiting room to find my bearded friend.

Back at the motel, I crawled between crisp sheets, shaking and sobbing.

I was into Joni Mitchell. I am a lonely painter. I live in a box of paints. And Picasso. Art is a lie that helps us realize the truth. I didn’t know whether I wanted to be a writer or a painter. I only knew I needed to find something in this short life to call my own.

I was looking for freedom. I didn’t find it. But I tried.

“What do you want?” my friend demanded. “Tell me what you want.” Told me I was his girlfriend now. Didn’t I know that? We had to do this. He couldn’t take me home to his parents carrying another man’s baby.

“Tacos,” I said. “I want tacos from Jack in the Box.” Greasy gold half-circles seared shut and placed in a little paper bag emblazoned with bright colors. I wanted them. They were my favorite drive-through and eat-on-the-run food.

My boyfriend drove to the nearest Jack in the Box for a sack of tacos — predictable bland shapes with familiar and hopeful packaging — and in the fading Texas sun, I ate taco after taco, seven in one sitting. With each greasy bite, I edged closer to the truth of my hunger and my pain: I wanted a baby, a baby of my own.

Babies were goodness, babies were hope, and babies were beginnings. I longed to begin again. Undo all the damage and all the loss.

When we divorced, I was the one who moved out of the house we jointly owned. I let him have everything, including our son. I ran down the front steps one night, my boy in his bed, my clothes in a trash bag.

I knew I needed to figure it all out, and I couldn’t do it there.

Not in the center of my sweet son’s life.

Making art was the only thing I thought my pain was good for.

By the time my best friend in California died, my son had stopped asking me when I was going to move back to Oklahoma City. Instead he asked me to buy him stuff, and called in the middle of the night with painful questions.

“I know why you left dad, but why did you leave me?”

It was dark by the time I was ready to leave the wake, dishes done and food wrapped up for later. My son was waiting in the car, avoiding good-byes. I lingered on the front porch, not wanting to leave the place I’d last seen my dear friend alive: upstairs in the master bedroom, eyes closed, loved ones in vigil. Aware he wasn’t gone yet, the gift of him still hovering, we hoped, forever.

I climbed behind the wheel and sat for a moment simply staring.

“Can we get out of here?” my son asked.

“Buckle up,” I answered.

On the freeway he fidgeted, rolled the window up and down over and over. “Will you take me to the promenade?” he asked.

“There’s food at home if you’re hungry,” I said. “Are you hungry?” Though I couldn’t imagine why he would be after all that funeral food — tiny plates of it free for the taking.

“I’m not hungry,” my son said. “I’m bored. And sick of this day. Take me to the promenade,” he said again. Demanding. Not asking. Telling me what I needed to do to make him happy.

“I can’t afford to go out again this weekend.” Not after the bankruptcy. Three days till I got paid, and he expected to be entertained, to be taken out for lunch and dinner, to cool places.

Guilt fun, that’s what he wanted: grief-deflecting fun. The kind that paid you back for loss and strife and absence. That’s what he wanted. And I wanted it too. Longed to distract myself as much as he wanted to be distracted: my work in permanent storage, my best friend dead, my child almost grown and a stranger to me.

“Let’s just go home.”

“I’m so sick of your poor mouthing,” my son said, disgust in his voice and on his face.

“What are you talking about? What more can I do? I don’t have any more to send your dad. I can hardly get by myself.” I told him the truth and instantly regretted it.

“They fucked you up.”

“What?”

“Your parents. Dad says they fucked you up.”

I whipped my right arm across the space between us like a guardrail, left hand on the steering wheel, right hand slapping hard against his mouth. Shut him up fast. Covered his mouth and silenced his voice and all the other voices in my head that said: this is what you get. You will never be quit of trouble. Stay ashamed and silent. Keep your place. You will never be what a child needs you to be — stable and dependable. Never. In the dark front seat beside his devouring need, eaten up with bloodguilt, ashamed I was still not a good provider, or nurturer, able to give my only child whatever he wanted, I changed lanes and prepared to take the Venice Boulevard exit, the quickest way to get us back to my apartment.

But not fast enough to avoid his fury.

“I could have you arrested,” he screamed.

Eyes swimming, I fought to keep focused, searching for the off ramp, Mama’s voice in my head: there’s something wrong with you, something wrong with a girl who does not love her mother.

“You hit me. You hit me. You hit me,” my son chanted, another child in a fast-moving car, letting another mother know he knew.

Knew all about me from the inside out.

He came out of me face up and royal purple, legs taut as caught roots. One eye open, one shut, upper lip a snarl, the umbilical cord — a spiraling rope of baby blue and pansy pink — trailing after him. Exploded into my life, another creature needing me, and judging me. All the fears, the desires, the moments of pain and the moments of tenderness too: nursing him, bathing him, rocking him, both of us alert as cats, pure animal instinct, protective and wary.

“It’s all your fault,” he yelled. “You are so fucked up! Fucked up!”

I heard his father’s voice in my son’s accusations and saw the uselessness of my giving up primary custody, the sad way I once again just accepted the space allowed.

His father’s words, his father’s voice streamed through him at me, warning me to keep silent, never share with our child the way his father held me down, handled the money, praised me and then slammed me, kicked my tires and tried to fuck my friends.

I slid into the far right lane, downshifted, and took the exit.

My son held his ears and kept screaming. “I hate you! I hate you! You are so fucked up!”

I turned toward him, worried that he might be sick.

He was prone to earaches. I could still feel the perfect fit of his fevered baby head under my chin, the weight of his body on my stomach, the sweet relief of sleep after so much pain.

“Are you okay?” I reached across to feel his brow and he knocked my hand away.

Almost there, just a few more blocks to my gated apartment with the garage below, roommate friends waiting, people who would help us, help me, help him. I checked the visor for the electronic opener. Get him home was all I thought. Get back to my room in my friend’s apartment and sort this out.

Not to be.

My son lunged across the front seat of the car. Grabbed my shoulders and lifted me up out of the driver’s seat. I held the steering wheel tighter. Tried not to lose my grip while he was losing it, crying and screaming and slamming me into the roof of the car, head pounding against the padded roof of the car. Boom. Boom. No room for me in my mother’s world and no room for me in my son’s, I held fast to the steering wheel and gave up. Floated through the sunroof into the night sky, away, away from this fresh failure. Looked down from there on what I knew was an Exxon station on the corner of Sawtelle and Washington Blvd, and veered into that dark lot. Business closed now, rush hour long over. With nobody around to help, I pulled in under the neon sign, managed to put the car in park, and turned to face the boy I had made, huddled against the passenger side door, trembling and scared and taking fresh aim.

“You will never see me again,” he said. “I’m leaving tonight. Not Monday. Tonight. Fuck this shit. I’m flying back tonight. Dad will change my ticket and you will never see me again.”

A grudge promise like the one I had once made myself, to take off and never look back. A girl who jumped off her family tree and ran, ditching the idea of blood bonds and vowing to never return. Never considering the truths you can’t jettison, the ones we all carry inside, from mother and father, and nature.

I was of a lineage that answered to no higher authority, a mother willing to destroy her offspring.

Rotten fruit.

I still didn’t know how to love with any ease. Didn’t know how to reach out to others with my soul, my heart’s mind. I was stranded. Stranded in a gas station parking lot, in awe of mother power: hers and mine.

Howl and hit and buy me pretty clothes. Call me ugly and pull out hair by the root. Laugh wildly at cruelty like it’s a joke. Like I was a joke. A joke I accepted and then tried to forget.

“What do you want to know?” I asked my son. “Ask me anything and I’ll try to answer.”

Somehow that simple offer settled him down for a bit. Long enough for me to restart the car, drive a half-mile down the street to my apartment, open the electronic garage door and cruise in. When the door shut behind us, I turned the engine off and stared into the darkness.

“I’m still calling Dad,” my son said, his eyes swollen, his hand on the door handle.

“Go on up,” I said. “I’ll be there in a minute.” I watched him get out of the car and leave the garage. Then I laid my head down on the steering wheel and tried to breathe.

I’d loved being pregnant with him. Didn’t have to think about a thing. Only had to eat right, and the round world of my belly grew on its own.

But all that changed after he was born.

What a good mother does, what a good mother should do, I didn’t have a clue.

Didn’t know what I was doing at all and that made my husband angry.

“She was so confident during the birth and the labor,” he complained to the OB-GYN. “Now look at her.”

“She’s not in control now,” the OB-GYN said. “Now she needs your help.”

Insufficient. Leaking mother blood. Shaking in a hospital bed. Tiny body squeezed out of me. Body of possibility and challenge, my son, seeing him in the world in the flesh, detached and separate, a being in and unto himself, seeing him alive and needy reignited all my fear: I can’t do this. How did I get here? I can’t do this; I’m all used up.

I waited in the dark garage for a while, then climbed out of my car and went upstairs to the apartment I shared with my friend and her husband and their two-year-old daughter.

As soon as I walked in the door, my friend turned off the TV. “What’s going on?” she asked.

“He’s calling his dad,” I said. “He wants to go home. Now. Tonight.”

I didn’t know what else to say or what to do, so I walked down the hall to my room and stood outside the door listening as my son talked on the phone with his dad. I heard him cry. He hardly ever cried. I stood listening, thinking maybe my ex would ask to speak with me. Get my side of the story. Then I remembered. He never wanted my side of the story. He’d told me over and over: we don’t need you. Our son doesn’t need you and neither do I.

A boy needs a father. Not a mother.

I thought I was doing my son a favor by leaving him with his father. A favor. I thought I could make the world a wholly different place for my son. Every time Mama left another husband, we lost a father. When I left my husband, my son did not lose his father. Leaving him with his dad when I left for grad school seemed like the right thing to do.

All the things I tried to forget about my own childhood, things I could barely live with: I chose not to share these with my son. All I did not want him to ever know — where I came from, what I had to leave behind to live — boomeranged right back at me.

I walked back into the living room. Sat down on the couch and waited to see what would happen next. My friend’s husband asked if I wanted a cup of coffee. I said no. After that none of us spoke.

After a while my son walked into the living room with his duffel bag over his shoulder. “Dad changed my ticket. I’m leaving,” he said. He kept his head down, wouldn’t look at me.

My girlfriend’s husband asked: “Should I take him?”

“Yes,” she answered.

He grabbed his keys off the coffee table and led my son out the door, down the stairs, and out of my life.

I didn’t say stop.

Didn’t open my mouth to speak.

Didn’t try to make him stay.

I remained where I was, in a ball on the couch in the dark, staring at the blank face of the TV screen.

Brought full circle back to the limits of love.

My son is forty years old now and I haven’t seen him since that night he left at seventeen.

I just didn’t get it. The lesson leaving taught. The isolation wrought of rejecting blood kin, the ones we can’t choose, or ever fully leave behind.

Chris J. Rice is a Missouri born writer/artist settled in Los Angeles after earning an MFA from California Institute of the Arts. A former foster child, Chris has worked as a field hand, a nurse’s aide, a preschool teacher, a newspaper researcher, a corporate trends analyst, and a public librarian. Her writing has appeared in Necessary Fiction, Pithead Chapel, The Citron Review, [PANK] Online, and The Rumpus. Roxane Gay selected her short story “The Lid” for inclusion in wigleaf’s top 50 (very) short fiction 2015. Pithead Chapel nominated her essay “Where She Came From” for a Pushcart Prize. “The Lesson Leaving Taught” is excerpted from a recently completed hybrid memoir entitled RAMBLER AMERICAN: AN AUTO- FICTION. She can be found online at https://www.chrisjrice.net/.

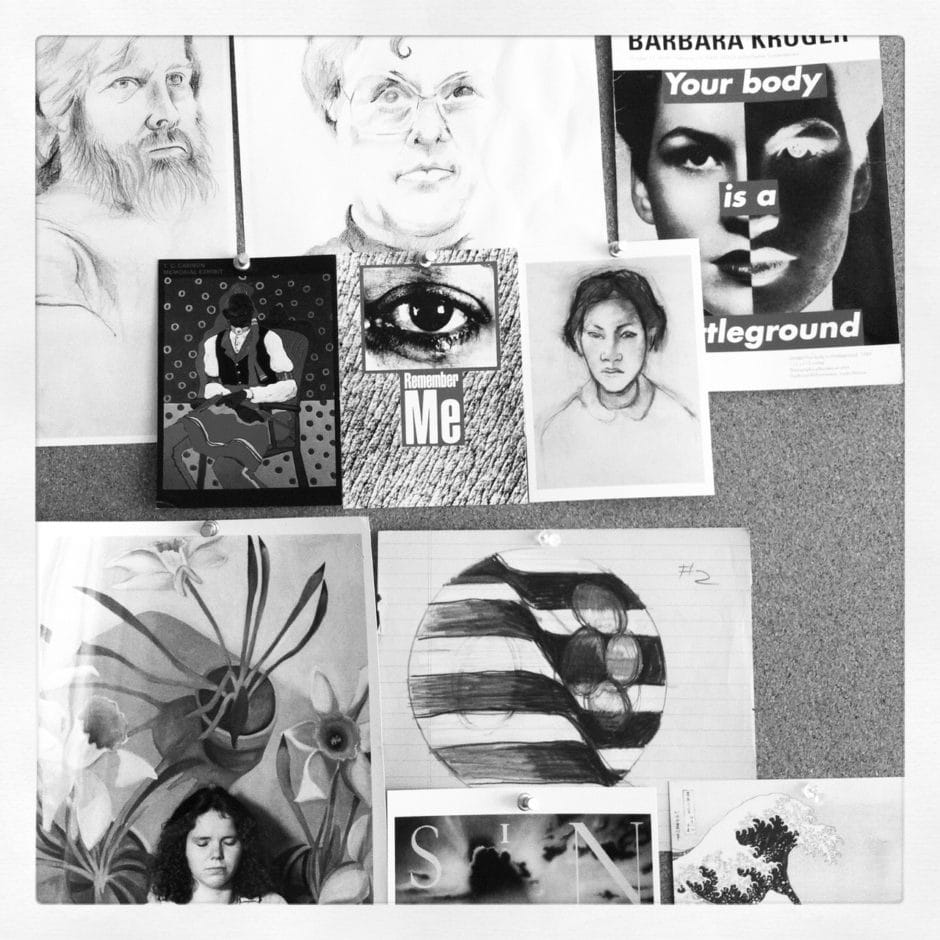

*Featured image by Chris J. Rice.

Click photo to read People Magazine.

4 Comments

Wow. Thank you so much for sharing your story. My heart hurts for you and I hope for you the courage to forgive – for yourself and your son. It’s never too late.

Oh Chris, you just grabbed my heart. I need to hug you. Love you.

I feel the sting. If you are both still breathing, it isn’t too late.

This essay is unflinching and bold, and drew emotions from me like a snake charmer serenading a cobra in a Marrakesh market. I am changed from reading this, and that’s what the best art does. Thank you for creating things in this world. Thank you sharing your art.