It wasn’t until he reached a town called Hempstead, Texas, just west of Houston, that Miles Paley realized Miss Snickerdoodle, his ex-wife Tara’s aging cockapoo, whom he had dognapped just a few hours earlier, had a serious flatulence problem. The eggy smell filled the cabin of his Jeep Cherokee with surprising speed, and when he opened the windows for the first time since they they’d left Austin three hours earlier, when the pre-dawn dew had obscured his side mirrors, the dog nearly leapt out to what would have been its certain, horrific death at 70 miles per hour on Route 290 East. One of the countless Ford F150’s that surrounded him blared its horn. The driver was a corpulent, pig-faced man, to whom he’d swerved so close when he’d grabbed Ms. Snickerdoodle by the scruff, he was able to make out the chaw that flew out from between his cheek and gum as he cursed wordlessly behind thick autoglass. The hate in his eyes shook Miles, so that his heart raced, and he pulled off the highway at the next exit.

“Easy, Hildy,” he said to the dog, more to reassure himself than it.

Hildy was short for Broomhilda, the name he’d wanted for the dog when she was just a pup they’d paid way too much to acquire from a breeder in Marble Falls. Presently, it was trembling, and letting out a sound that was somewhere between a cough and a dry heave every few seconds. Because the decision to take Hildy with him on his move to Florida was a last-minute one, there was no harness or leash, no treats, no food, and no water bowl. Miles picked up the animal and held its shaking body in his arms as he went into the Texaco convenience store.

“Hey there,” said a heavy-set and very pretty woman who resembled the actress Pam Grier, whom he’d had a crush on since seeing her on “Miami Vice” when he and his college roommate would do bong hits and watch that sort of thing.

“Morning,” answered Miles.

“Nice fur-baby you got there.”

“Yeah thanks.” Miles thought he saw something in the cashier’s eyes. A hint of hunger or loneliness, maybe. Were it not for his current situation, with this dog he’d stolen and with which he was planning to cross state lines in a couple more hours, he might have done his best to turn on the charm. Now, though, he felt perverse, like a drifter with a bad past, someone who ought not stay in one place for very long.

“What’s his name?”

“He’s a she. It’s Miss Snick – Hildy.”

Pam Grier eyed him with suspicion. “Hildy, huh? Why’s she shaking like that?”

“Little carsick, I think. Do y’all have leashes? Like for dogs?”

“Yeah I figured that’s what you meant. Let’s have a look-see.” She came out from behind the counter, and gave Miles a little sideways smile as she shimmied past him with a “Scuse me.” He followed her down the aisle, watching the little Santas on her seasonal yoga tights dance, and imagining her in a hotel room, disrobing slowly for him.

“Not sure we’ve ever had any leashes, but if we did they’d be over here, with the pet stuff,” she said.

Miles indiscriminately grabbed some dog food and some treats, as well as a couple of plastic bowls that had pawprints on them.

“Thanks,” he said, motioning for her to go ahead of him. The egg smell rose from the dog, and he could tell Pam Greer caught a whiff of it.

“Sorry about that,” he said. “It’s part of the carsickness, I guess.”

“Hers or yours?” she teased, with a backward glance over her shoulder that made Miles shake his head.

“You’re bad,” he murmured.

“Can be,” she smiled.

She made her way back behind the counter, and before he could ask her name, which would have been the clear next move, the dog heaved out a gob of bile that fell short of Pam’s yoga pants and landed squarely on the plexiglass, obscuring some scratch-offs and an ad for Skoal chewing tobacco.

“Oh shit!” Miles said, holding Hildy at arms length and away from the cashier.

“It’s okay, baby,” she said, deftly wiping up the mess with a wad of paper towels. “We good here.”

“I’m so sorry,” added Miles, the rejuvenating tingling in his groin now gone, replaced by sheer and utter mortification.

The Pam Greer lookalike shook her head and waved her hands in front of her, the paper towel dripping with mucous. The sexy glint in her eye was no more.

“We good,” she repeated.

“Here,” said Miles, awkwardly dropping a five dollar bill on the still wet counter.

“That’s not – okay. Bye now. Hope your baby gets to feeling better.”

After an awkward walk around the garbage-strewn parking lot, Hildy at the other end of the extension cord Miles purchased as a makeshift leash and knotted around her collar, Miles and the dog returned to the Cherokee.

“Nothing, huh?”

The dog was panting; even though it was mid-December, the heat and humidity from the Gulf were formidable. Miles felt it too, and as he mopped his brow, checking himself in the rear-view, he shook his head with a little laugh. During his brief flirtation with the cashier, he’d been picturing himself at 21 – slender, tan, with shoulder-length, feathered hair the color of sand dunes. This man, balding, paunchy, and perspiring, was a far cry from the Don-Johnson-in-Training he’d once imagined himself to be.

“Okay, well, we’re off,” he said to Hildy, who gave him a good-natured look, or so he thought. He’d felt they’d had a connection back in her puppy days. When she fussed, it was Miles who could calm her, by holding her close to his heartbeat. Tara had never had that skill with her, and he could tell she resented it.

“Don’t be jealous,” he said one night as they sat drinking wine under blankets, their back yard firepit warming them. Miss Snickerdoodle, as the pup had come to be known by this point, was nuzzled under Miles’s cover, her snout tucked under his arm.

“What?” Tara was tipsy; Miles always knew. It was something in the timbre and tone of her voice. Not slurring exactly. It was almost like her speaking voice went down an octave. He’d always found it weird, but never said anything.

“It’s not something you should take personally. See dogs always imprint on an alpha.”

“Oh so you’re the alpha, then?”

“Damn right,” Miles said, appealing then to the sleeping puppy, in that goo-goo ga-ga voice people use with dogs. “Isn’t that right, HIldy?”

“MIss Snickerdoodle,” Tara corrected in that lower register of hers.

“Yeah right,” said MIles, ending the conversation there.

“Alpha. Ha,” said Tara, getting the last word.

It was snippy conversations like this one, often witnessed by the pup, that eventually led the couple to agree that their marriage had become loveless. They tried counseling, which only served to underline what was already obvious to them both: that a $2,500 dollar Cockapoo, though undeniably adorable, was not a substitute for the child they could not have together. Neither Miles nor Tara wanted to blame the other, but it was impossible to avoid. In the end, which came not long after Miss Snickerdoodle’s entrance into their lives, they went their separate ways. Tara kept the dog, and Miles moved to a rented cottage just off South Congress. Only a few miles away as the crow flew, but they rarely saw each other in the fifteen years since.

Miles’s phone dinged just as he merged onto I-10 East. It was Tara. The contact came up as “Maybe WIFE.”

“Oh Jesus,” Miles said aloud. Hildy, who’d been asleep in the passenger seat, swaddled by one of Miles’s dirty t-shirts, opened one eye and regarded him. The other eye appeared glued shut by a reddish film of some kind. It made Miles uneasy, and he looked back at his phone.

hey sorry to bother you but were you here this morning? early?

Miles gripped the steering wheel tighter, as he found a good cruising speed. Did she have one of those Ring home surveillance systems that everyone (except him) seemed to have these days? He didn’t see one. He certainly checked.

weird question i know. just had this feeling. now can’t find miss sd

A feeling? Okay, okay. A feeling is fine. A feeling won’t hold up in court.

A feeling.

Before he could finish telling Siri to text “WIFE,” his reply that he was driving and couldn’t talk, the phone rang. Almost by instinct, he hovered his thumb over the green “accept” button. (They’d made a pact never to let the other go to voicemail, and had kept that particular promise religiously.) He stopped himself, and let it ring instead. A minute later, the phone indicated a voicemail message, followed by a new text.

call me. please

About an hour and a half later, Miles found a Petco that wasn’t too far off the highway, and he bought the dog a proper leash and harness. He didn’t feel right tugging it around by the neck, especially not with an electrical cord. She was an old lady, after all. And for a short while, thanks to the harness, which actually fit correctly and was not unattractive, with a stylish black and white floral print, Miles felt at peace. He walked Hildy on the sands of a beach on the shores of Lake Charles; knowing he was officially no longer in Texas also lightened his heart considerably. Hildy moved slowly, but her other eye was now open, and she’d managed to groom herself free of the gunk that had been keeping it shut earlier. Even the unseasonable heat felt less oppressive here. This, he knew, was in his head, but still he took the moment to sit in stillness, enjoying it.

Again the phone rang, and the words “Maybe WIFE” appeared on the screen. As before, he let it go to voicemail. Then he pressed the playback button. The first message was a verbal version of the initial text. She sounded almost chipper: “Hey, I know this is weird, but did you come by early this morning? Just had a feeling. Call me. Thanks.”

He then listened to the message she’d left moments ago. None of the feigned friendliness remained, replaced by hysteria that put Miles right back to their early days in Texas, where they’d moved to raise a family. He hadn’t heard anything like it since the third time the IVF treatments failed, and the team at the fertility clinic provided them with materials about adoption as a next best option. In the car on the way home she wailed like a banshee. The sound of true, elemental, primal sorrow. Plain and simple. Their relationship couldn’t survive it. Nothing could.

“YOU’VE GOT MY FUCKING DOG, MILES! I KNOW YOU DO! I DON’T KNOW HOW I KNOW IT, BUT I DO! GIVE ME BACK MY FUCKING DOG! GIVE HIM BACK!”

Miles raised an eyebrow and traced the leash to the shade of a bush where Hildy lay on her side, looking more peaceful than she had the entire trip. It seemed as safe a time as any to do what he did next.

“Okay, Tara, okay. Take it easy,” he said over her screaming. She’d resumed it as soon as she picked up his call.

“TAKE IT EASY? Okay, I’m calm. Okay? But I know it, Miles. I just know it.”

“Slow down and tell me what happened.” Miles was being condescending, and he knew it. He also knew that Tara would have to back off of her assertion, because of how crazy it sounded. (Never mind that it was true.)

“She’s gone. Miss Snickerdoodle. I can’t find her anywhere.”

“Maybe she’s run off to the golf course, like that one time, remember? When they let us ride around on a golf cart looking for her?” That day, although forged in the same panic she was experiencing now, had actually turned out to be a good one for Tara and Miles. They bonded on that ride around the course, and felt pure joy when they found Miss Snickerdoodle, covered in mud, on the banks of one of the water hazards, a mangy looking mutt twice her size there beside her.

“What? No! She’s old, for god’s sake. She’s not going anywhere.”

Tara was no longer accusing Miles. She was asking for his help. Miles cupped his hand over the phone as Hildy stretched languidly, letting out a contented yawn.

“Listen, Tare, I’d love to come help you look for him, but I’m actually in the process of moving,” said Miles.

Tara was silent, and after a few seconds, Miles added, “I was going to tell you. I just…”

“No, no,” she answered. The forced cheeriness had returned. “End of an era, I guess, right? Where you moving to?”

“Florida.”

“Florida?”

“Of all places, right?”

More silence. This time it was broken by Tara.

“Our governor not crazy enough for you?” she joked.

“I think Florida’s got him beat,” Miles replied.

Satisfied that she’d given up on her intuition about the offense he’d committed, Miles suggested she might call one or both of her brothers for help.

“We don’t talk much anymore,” she said, sounding sad and lonely. Her tone made Miles feel guilty. He knew perfectly well that she and Jack and David were estranged. Mutual acquaintances had kept him in the loop over the years. He’d invoked them on purpose, to make her feel bad, and now he was sorry for it.

“Anyway, Tare, I gotta get back on the road if I want to make it to Florida by nightfall,” he said.

He heard his ex-wife sigh, her loneliness accentuated his own. “Right. Safe travels, and it was good to hear your voice after all this time.”

“Yours too,” he said, supposing he meant it on some level.

Hildy yelped loudly. Miles’s thumb was on the red “hang-up” button, which he pressed at that very moment. He cursed loudly, then bent down to tend to the dog, who held her paw gingerly off the ground. She yelped again when he pulled the barbed sandspur out of her pad. He gathered the dog up in his arms and carried her back to the car, where she drank some water from one of the bowls he’d purchased back in Hempstead. Miles’s heart was racing again, this time wondering whether or not Tara had heard her dog cry out in pain as they had hung up the call. He sat with his hands on the steering wheel, not going anywhere, waiting for her call. Five minutes passed, and he figured she’d likely have called him right back had she heard the yelp. Hildy settled back into the nest of Miles’s dirty laundry, and the two set off eastward towards their destination.

Thanks to light traffic, favorable weather conditions, and only one pitstop for gas and bathroom, the GPS guided them into Pensacola Beach just as the sun was setting over the gulf. The causeway lights came on as he was crossing, which felt to him like a good sign, like this move he was making would be a good one.

That changed when he saw Hildy. After having finally arrived at the hotel, and trying to rouse her from her nest in the passenger seat, he saw that she was trembling – spasming, more like – every few seconds, and that both of her eyes were now shut, and the rheumy stuff that sealed them formed a thick, leaky film.

Miles got back behind the wheel, and got directions on his phone to a 24-hour veterinary hospital that was a few miles away. It was dark now, and he made his way with caution down the unfamiliar roads. He had opened the windows, because the eggy smell had returned. The dog’s breathing had changed, and she appeared swollen somehow. The coughing dry heaves Miles had noticed coming from the dog way back in Hempstead were protracted now, so that the dog seemed almost to be moaning.

“Come on through,” the receptionist at the vet’s office said, as she made her way to open a swinging door that allowed Miles to carry the convulsing dog behind the counter. “We’ll get your paperwork later.”

The young woman, nondescript and professional in hospital scrubs and rubber shoes, led him through a door and into an examination room.

“It’s okay, baby,” the receptionist said as she stroked the dog’s head. “What’s her name?”

“Hildy. Or Ms. Snickerdoodle. She answers to both.” Miles felt ridiculous after he said this, and not just for the obvious reason: that a dog having two names is unnecessary and stupid. The other reason he felt idiotic was that this dog was clearly not going to answer to any name, in the condition she was now in.

“Okay sir, well you stay with…with her, and the doctor will be right in.”

Hildy’s body, though convulsing every few seconds with terrible tremors, as if an electrical charge were going through her, was otherwise still, flat as a bearskin rug on her belly, her four paws splayed in four directions. Without thinking about it, Miles reached for his phone. The words “Maybe WIFE” appeared as the most recent call. She was so joyful the day they drove up to Marble Falls to bring Miss Snickerdoodle home. The dog, too, seemed overjoyed, but that could have just been due to the fact that she was a puppy, and puppies were joyful by nature.

The doctor was a large, handsome man with graying red hair and a Scottish accent.

“Oh you’re a sweet old girl, aren’t you?” he said in a melodious voice full of an otherworldly empathy that touched a chord in Miles Paley, who began to weep quite unexpectedly.

“I’m so sorry,” Miles said, as he reached for some tissues to wipe away the tears and snot that came suddenly and with force.

“Doc’s got it from here, sir,” the young woman, who had returned to the small room, said, taking Miles gently by the elbow.

“It’s okay, Linda,” the doctor said. He had a gloved hand on the back of the dog’s neck and was rubbing its scruff gently. “I don’t want this gentleman to have to wait.”

“Yes, Doctor,” the receptionist said, leaving the two men alone with the dog.

The doctor asked Miles a number of questions about the dog’s medical history, none of which he could answer, aside from the age. He chalked it up to how upset he was, and the vet said that he understood.

“Listen, I want to speak plainly. May I do that, please?” he asked.

“Of course,” said Miles.

“The swelling you’re seeing is severe edema. Her organs are failing, and she’s in a great deal of pain.”

The vet described treatments they could try, but Miles knew from the tone of his voice where the conversation was headed.

“I couldn’t tell you how close she is to passing naturally. All I can say is that however long it takes, it will be unpleasant for her, even with pain meds. It’s entirely your choice, of course,” said the vet.

Miles chose euthanasia. When the vet asked him whether or not he’d be staying in the room, Miles reflexively answered that no, he would be leaving. But just before he left the little examination room, through the door the vet was now holding open for him, he said, “No. I’d actually like to be here for her.”

The vet’s eyes brightened, and a smile came to his face.

“It makes a difference. To the animal. Seems silly, but I know that it does.”

“Yessir,” Miles said

The doctor explained that the procedure would be painless and humane, that Miss Snickerdoodle would lose consciousness very quickly, and would feel nothing other than the release from the immense pain she was currently in.

“Is it alright to hold her?” Miles asked.

“Of course,” the doctor said. “Just mind the tubing.”

MIles leaned over the chrome table, covering the dog like a blanket. Carefully, gently, he tucked her snout under his arm, as he had when she fussed as a pup. Now, as then, the dog settled. The trembling ceased, as did the dry moaning breaths.

With the doctor’s gloved hand on his shoulder, Miles stayed that way, draped over the dead animal for a few minutes. He was glad to have been there for this creature in her final moments. He was proud of himself for staying.

“Thank you,” he told the veterinarian, as he stood and reoriented himself to the changed world around him. “Thank you for everything.”

Dan Fuchs has published short stories in the Syracuse Review, TeachAfar, and Free Spirit. He lives with his family and a sweet, old German Shepard mix named Ally in Orlando, Florida.

***

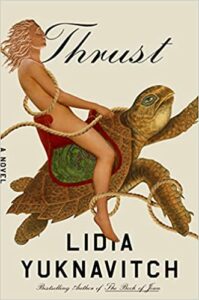

Have you pre-ordered Thrust?

“Blistering and visionary . . . This is the author’s best yet.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

***