by Bruce Meyer

My college roommate, Greg, kept a box of papers in the bottom drawer of his desk. He opened the box one night and told me his entire life was made of paper. There was an adoption record – no former names, Christian or surnames, stated – and a newspaper clipping from the Toronto Star where a sad-looking child, his eyes fixed on the floor in front of him was featured as ‘Today’s Child.” That was Greg.

He stared at the neatly snipped rectangle, yellowing and growing brittle with age, and said simply, “That’s the only picture I have of my childhood. You see? My white family took the trouble to scratch out my real name. They wanted me to be their Gregory. They wanted me to be someone else. And so, I obliged them. It was better than going back to the residential school.”

I wondered how he could go through life, at least to this point, a high achiever on both athletic and academic scholarships, someone with a big ‘He’s-going-to-be really- someone’ sign hanging around his neck, yet remain humble, fun to hang out with, considerate. He’d become the sort of guy who brings you chicken soup when you have the flu.

Yet for everything he is, he had no idea who he was.

I wanted to feel his pain, but I couldn’t fathom what that pain could be like. My grandparents and parents had gone to the same college at the university. I was simply falling in step, as was expected of me. I was not merely part of a lineage: I was white privilege.

“How did you…”

“Cope? Stay sane? I had to live with it. Hard as it is, I figured what is just is. I didn’t know a different life. I knew mine was mine no matter what they called me.

“Imagine,” he said, “if someone came into your house when you were four or five and ripped you from the arms of your mother or grandmother. How would you have felt? At night in St. Bartholomew’s School I’d lie awake in the dark and listen to the other children in the rows of white iron cots as they sobbed into their pillows. Sobbing was a good sign. It meant you still had something to miss, something to live for. Those who stopped sobbing would be found hanging in the basement of the school or frozen in the forests beyond the school’s grounds.”

“Do you have any idea where you’re from?” I asked him as he folded the clipping, set the papers in order, and put the lid on the box.

“Not a clue. I have memories, though. An old woman. I can’t even see her face clearly. She is standing beside a lake and she’s staring at an island across the waters. It isn’t a large lake, and the island in the middle of it isn’t all that big either. It could be anywhere. This whole frickin’ country is made of lakes and islands. I keep going back there in my dreams. I keep trying to talk to her, to ask her questions, but because we only meet in dreams, the sounds won’t come out of my mouth. She does speak to me sometimes, but it’s in a language I don’t understand, and that makes her seem farther away than she really is. I’d love to know who and where she is. She is old in the dream and has probably passed on by now.”

Everything in Greg’s dreams, he told me, happened by moonlight. He couldn’t see where the light was coming from. Then he’d get playful and ask, “Who the hell lights our dreams? I mean, is there a gaffer pulling cables and setting the blue flood just right so we can see where we’re going and not bump into the more solid illusions?” He’d laugh, but I could tell that the laugh was masking a very deep pain. It wasn’t a happy laugh.

Greg was my closest friend at university, my spirit double, if there is such a thing, someone for whom I’d be honored to be a shadow. We’d talk about anything, but mainly about how we know or don’t know who we are. Greg knew what he wanted to become. He was fascinated by the law. He’d ask me why it was legal to kidnap a child, and I’d tell him I had no idea, and that I thought all kidnapping was illegal. He’d agree. What was wrong was wrong, he’d insist, and he’d say that someday that wrong would have to be undone.

He got accepted into law school.

“I’m not as happy as my folks.”

He never called them his family, only his “folks.” He said he never felt completely a part of their lives but was more of a good deed they felt they were doing, a project that was coming to fruition like pulling the last thread and watching a ship pop up in an empty bottle, the way he described it.

“I’m going on to law school because it is another step on the road back to where I need to be.”

After graduation, we lost track of each other until I ran into him as I was going into one of our old lunch haunts near the campus and he was coming out. We talked for a few moments. When he said, “family law,” there was something emphatic about the word ‘family,’ as if he felt that the law was a means of turning back the clock to find what he had lost. In the chapters of parliamentary acts and statutes, there was a blood connection he was seeking.

He asked me if I had a week off this summer. I did. “We can do the buddy thing and drive north and look for the island.”

“Good luck in that,” I said.

“No, I mean it, man. Besides, I don’t have a license and you do. The Griffiths told me I had to earn a car, and I can either have wheels or I can pay my fees. There’s more future in my fees. Besides, I need you to be Tonto to my Lone Ranger. You can sense your way to the lake with the island. I trust your instincts.”

When I picked him up at his apartment in the stillness of the pre-dawn damp I told him we were going to start with the biggest island and then work down to the smallest. It seemed logical.

The biggest island on a lake is Manitoulin, a belt of limestone that rises out of the waters of Georgian Bay and defines the meeting point between the three Great Lakes of Superior, Huron, and Michigan. It is the Niagara Escarpment after it has drowned off Tobermory and the Bruce Peninsula and risen to life again to the north.

I’d read a travel magazine in a dentist’s office where the writer said the island had been destroyed by an enormous forest fire around the time Shakespeare lived, and that after the War of 1812 it had been resettled by indigenous peoples who remained loyal to the British and got the raw end of a treaty. The writer described Manitoulin as a Chinese puzzle box of islands.

“Imagine,” said the traveler, “the largest island in the world on a freshwater lake, and one that island is the largest freshwater lake on an island, and in the middle of the lake is the largest island on the largest lake on the largest island on the largest lake in the world.” Once I sorted out the knot of that sentence I felt that the best place to search for an island in someone’s mind is to begin with an island of dream-like anomalies.

As we drove north following the shoreline of Georgian Bay where we stopped every twenty miles to look at islands only to have Greg shake his head and say, “Not that one,” we arrived in Rainbow Country. We didn’t see any rainbows. Greg shrugged and looked out the window. “Just a lot more rocks and trees,” he said. “I feel as if we’re trapped in a Group of Seven painting.”

But as we turned along the North Shore and headed west toward the Algoma Region, the hard, rugged terrain of marshes and mountains, the landscape became the dream-like terra incognito described by the magazine writer. Granite outcrops rose up from drowned pockets. Bulrushes and beaver lodges emerged from glistening rivers that snaked between sharp granite clefts. We passed through the White Fish Nation and Greg said he was feeling strange, as if something in the pit of his stomach was trying to make him ill. We pulled over and he threw up into a ditch or marsh marigolds that are commonly known as Urineworts because they bloom like lotuses in stagnant water.

“So what hit you?” I asked.

“I feel a lot better. I don’t think it was anything I ate because you ate the same coffee and doughnuts back in Parry Sound. I think it was something I feel I had to get rid of, something in my gut that wanted to come out. I’ve never had a feeling like that before.

“Up ahead,” Greg said, “just on the edge of the res, there are rocks. They are stranded on flats where the granite becomes a road of limestone.”

“That’s a good start,” I said. “More where they came from, I’ll bet. How do you know there are rocks?”

“I don’t know. In one of my dreams the rocks were singing. Weird, eh?”

“Yeah, weird. I’m driving you around to look for an island that could be any island in a country that boasts several million islands and you remember singing rocks. Remind me again that you never dropped acid.”

“Man, I know it’s crazy, but they’ll be there.”

Within a few miles the topography changed again to low, flat limestone, and on the exposed bedrock surface sat enormous blue stone boulders and nothing grew around them. They looked as if they had just dropped from outer space.

“That’s them!” He shouted. “Those are the rocks!”

And electric sign by the side of the road announced that the iron swing bridge to Little Current on Manitoulin Island would only remain open for another ten minutes. If the single-lane span swung open, it might remain open for an hour or more to let the sailboats of wealthy Americans pass from Manitouwaning Bay to the North Channel above the island. I explained this to Greg.

“Good you’ve done your homework.”

“Just read a map and a guidebook,” I said. “Do you want to stop at the rocks?”

He looked at me as if I was daft. “I don’t feel up for a sing-along.”

“You really are sure they sing, eh?”

“It was just a dream. You can’t get blood or a good tune out of a rock.”

It was ten a.m. when we arrived in Little Current, the biggest town on Manitoulin. A policeman waved us off the main road to a detour and as we turned he halted us and leaned in the car window.

“Parking’s over there for the festival.”

I pulled into the first empty space.

“Wanna go to a festival?” I asked.

Greg shrugged. He didn’t care one way or another and because we were driving nowhere in particular he got out and we walked back to the highway into town. A parade of floats pulled by red an orange tractors was inching its way toward a field at the end of their procession. Girls on the floats were waving and shouting to the crowd. A high school marching band, off-key, with a very noticeable glockenspiel, tramped by. On another float the local Junior B Hockey team was pointing to the crests on their jerseys and raising index fingers to tell everyone they were number one. The end of the parade was a cortege of Provincial Police cars, an ambulance, a firetruck, and the Mayor holding up a fluttering town flag as he sat on the back shelf of a red convertible.

“Canadiana at its finest,” I said.

An old man in a red and black bush shirt walked up to us and handed us each a palmful of red berries.

“Be a haw-eater!” he shouted.

There was a woman standing next to me. Her white hair was pulled back behind her head and fastened by a leather barrette with a stick through it. Her shirt was embroidered with a dreamcatcher – a stick bent into a circle and woven with gutting and beads on the threads to catch the sad and insane imaginings of a sleeper as they pass from the conscious world to the inside of a dreamer’s head. I’d seen dreamcatchers for sale in one of the occult shops near the campus and had thought of getting one for Greg but didn’t when I thought he might think I was joshing him about his nocturnal habits or his indigenous roots. I asked the woman what the berries were.

“Hawberries. They only grow on the island, and appear only during a July full moon, a time when the face of the old woman shines down on Turtle Island. Food of the Great Spirit,” she said and smiled.

The hawberries were about the size of Saskatoons which I’d tasted out west in a golf course parking lot in a coulee near Regina. But the hawberries were softer like blueberries and blood red. They were as sweet as blueberries but with the aftertaste of pomegranates. I was about to tell Greg we should buy some to eat in the car, but when I turned away from the woman to speak to him, he was staring into the berries in his hand. His eyes were wide as if he had discovered a wound in his palm.

He picked up the first one, rolled it in his fingers, and set it in his mouth. He didn’t hear me when I said his name, but just stared at them as if looking into a clear lake and trying to see the rocks on the bottom through the ripples of the surface. Then he ate another, and another, before he sank to his knees, and began to weep and beat the ground with his other fist.

“I need more,” he said.

I found another lady who had been selling small baskets of them on a table by the road, and I bought her last pint. Greg was now bent over, grabbing at handfuls of dirt on the shoulder of the road and tossing them in the air. He was freaking me. People were standing around him, kneeling, asking him if he was all right. Someone wondered if he was having a seizure. He couldn’t reply. His shoulders were heaving as he sobbed.

“I need to find my grandmother,” he said, looking up, his eyes full of tears. “I need to find the old woman. These berries are the taste of her spirit.”

The woman who sold me the berries bent down and laid a hand gently on Greg’s shoulder.

“I think I know why you are here. You are one of the searchers, aren’t you. You are one of the lost who has come home. I know it. I see it in your face and in your eyes. I can see through your tears. The Truth and Reconciliation Report called to you. It awoke old dreams in you, dreams that you thought you had buried or had lost on your journey. You are coming home, though you are not all the way there yet.”

Greg looked up at her. I could see in his eyes the suffering pouring out, a terrible pain he had kept bottled up inside. This was not the Greg I knew, the Greg who always had a quick quip, a good story, or a ‘you gotta see this’ experience he found on the web. He was a dream caught in an invisible dream catcher, the prey of a tormenting spider into whose web he had stumbled. This Greg was someone else – the person I had heard talking in his sleep, the person who woke, weeping, and asking for his grandmother and trying to describe the island he had seen in the distance of those dreams.

The berry woman put her arms around Greg and began to rock him as if he was a child. Then she spoke. And what she said startled me. The words were those I had heard Greg speaking in his restless dreams, the words I wished I had recorded and played back to him the next morning.

She looked up at me and said, “Can you take him to Wiiki? I mean, Wiikwemkoong?”

She explained that part of Manitoulin had never been ceded in a treaty and remained an independent nation within Canada. I had no idea such a place existed, a place within the nation that was not part of the country.

“Go down the highway. When you get to Manitouwaning, turn off but don’t go all the way into the town. There’s a road that will take to you Wiikwemkoong.”

“What will we be a looking for there?” I asked.

“Someone who might be able to help him. I’ve been whispering Anishinabek to him and he understands what I am saying though he can’t reply in the language.”

The woman and I helped Greg down the road to the car.

“Are you sure you’re up for this, bud?” I questioned. Greg nodded though he fought in his throat for every word.

“Yes. I want to go there now. It isn’t far.”

I thanked the woman for her kindness. She said it was not kindness but what family does for its own. I asked if she was related to Greg, perhaps a cousin or an aunt, and she shook her head.

“We are all brothers and sisters,” she replied and turned back up the side street to the main road where she vanished..

As we drove past the outskirts of Little Current I asked Greg what the hawberries had done to him.

“It’s not what they did but what they said. When I was a little boy, before the scoop, the old woman fed them to me. I ate them from her hands and when her hands were empty I walked up to a bush and ate them fresh off the branch.”

Down the highway, we saw the sign and the turn off for the Unceded Independent Nation. The sign told us we were leaving Canada and that the nation had its own police force. It advised us to drive carefully.

“I know this place,” Greg said as we approached a small building with a shaded porch out front. In one corner, a woman listening to a radio was seated in front of a sign offering bannock for $2.00. An old woman sat at another table. When I approached the bannock seller, she pushed a pamphlet toward me that listed all the things we could do in Wiikwemkoong – the theatre, the ruins of an old residential school, selected places to fish if a license was obtained from the band office, and a map showing where the road became a dotted line and vanished into the bush. “Drive slowly,” she said.

Then she looked at Greg and put her hand over her mouth.

“You, you look like my grandfather. You stand like him. You have his eyes. My sister had a grandson who was taken. We all have known those who were taken. My sister and I were taken but we returned. She was old enough to remember who she was and where she was from and the first chance we had, we came back. Oh, if you are who I hope you are, you have come a great distance and learned great strength to be here. I can see it in your face. But do you know who are you or are you among those who only remain here in their dreams?”

Greg began to sob. I put my arm around him. The woman came around to the front of the table and opened her arms and embraced him as I stepped back.

“I don’t know who I am,” he said, fighting back the tears. “I only know that in a dream I am standing by a lake with an old woman. The moon is full. The light is breaking on the water, and she feeds me hawberries. I had forgotten how they tasted until an hour ago when a woman, her grey hair pulled back and a dreamcatcher on her shirt gave me some to taste, and the taste brought back the pain, the pain of leaving, of being torn away from my grandmother’s arms.”

“Are there any records?” she asked.

Greg said no. All he had was a clipping, and the name in the clipping from the newspaper had been scratched away because his new family wanted him to forget who he had been.

“I want you to be my guests for the night,” the bannock seller said. “I have a place just down the road. Not much of a place. If you have bedrolls you can spread your gear on my floor. I’ll have some friends over and you can talk about what you’re going through because they’ve been through it, too.”

We ate a huge dinner. I was hungry. After eating I thought I’d never have to eat again. Everyone brought something. Greg and I fell in love with cedar tea and we emptied several jugs of it. Fresh salmon from South Bay. Venison. Fiddlehead greens someone had frozen two months before when the ferns were tight. They’d been cooked in butter and wild sage.

I didn’t want to say much. I wanted the evening to be about Greg. He had so many questions, yet they had so few answers. I could feel their empathy for him. Empathy was something I’d never know in those proportions from my own family. I envied him. I marveled at the love they expressed for him. It had nothing to do with duty or traditions or keeping up the family name. They spoke of the spirit.

An old man turned to me and asked what I knew about ‘Indians.’ The gathering laughed and slapped their knees when he said the word ‘Indians.’

“You know, he said, the people. What do you know about the people? We’re not from India. We’re from these parts.”

“I’m just the driver,” I said. “I’m driving my friend to look for an island in a landscape of islands as he searches for his past. It’s the least I can do for him.” Greg grabbed my knee and shook it and smiled.

“But you must have had some experience with the people,” the old man said. “We’re here. We’re not invisible. We don’t just live in movies.”

“Well, this isn’t much of a story,” I said, “but when I was a teenager, I wanted to be a hockey player. I found out there are two types of hockey players: good ones and bad ones, and I was one of the awful ones. I got invited to a hockey college out west, just south of Regina in a little town called Wilcox. The college is Notre Dame. They produce guys who go to the NHL. The college gives them a solid education, but when I got on the ice with players who really were hockey players, who you could point to and name the team that would likely draft them, I was out of my depth. I didn’t get accepted and it was probably a good thing because my family kept telling me they weren’t going to buy me new teeth. Part of the experience, though, was when the coaches took a van load of us up to a bison ranch in the Blue Hills about ten kilometers south of the school. I looked at the hairy, fly-infested bison and they looked back at me, and I thought, ‘so what.’ Then I wandered off.”

“At the edge of the ranch, on a promontory of the hillside, the ground was covered in wild sage and fell away steeply on three sides. I could see, spread out before me, Estevan, Weyburn, Moose Jaw, and Regina way off in the north, and the small towns of Avonlea and Wilcox at the foot of the Blue Hills. It was breath-taking. I was amazed how far I could see, how the whole world, perhaps even the universe spread before me, and when I looked down, I realized I was standing in a medicine wheel.”

“The wheel had a center stone of domed white marble, a polestar, and round it was a ring of other white stones set in constellations – the Big Dipper, the Great Bear, Orion’s Belt – the whole the sky was laid out in stones. I was standing in the center of the universe, maybe in the heart of eternity, and I felt as if I existed yet didn’t exist because I was part of everything around me as far and maybe farther than I could see. The wheel was a map of forever. Then I thought, I’d better get out of this. I felt as if I was violating something sacred without realizing what I was doing.”

Everyone at the gathering nodded, especially the elders. The old man spoke up, “You ought to take your friend Greg here to Dreamer’s Rock tomorrow. If you came in by the Swing Bridge you probably drove right by it without realizing it. If you saw the Bell Rocks you went too far toward the island.”

“The Bell Rocks?” Greg asked. “Are those the singing rocks? I have recollections of them from my childhood.”

“If you tap one with a piece of hard stone all the others will ring. They are made of the same stone as that Stonehenge thing over in England. I saw that when I was stationed in England during the war. I wanted to tap the Stonehenge but a man there said I couldn’t.”

“I said, ‘why not,’ and the man said, ‘because you will break it.’”

“What is Dreamer’s Rock?” Greg asked eagerly. “I’ve come this far to find the old woman who lives in my dreams. Will I see her if I go there? Is it a place to dream?”

The old man was silent for a moment and folded his hands.

“Maybe you are just looking for the lake of the old woman, Mindemoya. Good haws grow there. But Dreamer’s Rock? To go there,” he said, “means a person has been called to find who they really are. It is a place of the spirit quest. You must climb as high as you can go, and then go higher, ascending the bleached white skull of the world, and then lie down in a hollow made in the shape of the people. Only you can go there,” he said, looking at me. “I mean, you can go along to make sure he doesn’t fall off the slope on his way up and land on his death, but the final height is something only he can attain.”

So the next day, I drove Greg to Dreamer’s Rock and made the long climb up with him. I went with Greg as far as a natural vestibule near the top where white rock formed natural benches. He took off his shoes and socks, removed his belt, and set his wallet and pocket belongings on the stone shelf. I saw him scramble up the side of the dome and for a moment stand at the top, teetering and looking as if he was dizzy. He called down to me that there was no perspective up there, nothing but clear blue sky above him while below he could see Lake Superior to the west, Lake Huron to the south, Georgian Bay to the east and the tip of Lake Michigan to the southwest. Then he lay down in the niche the old man had told him about and I could not see him.

When he came down, sliding on the rock face as if he had just been born out of the sky, he said everything had changed for him. He said he lay down in a hollow. The natural dip in the white stone was the length of a person’s body, a cradle. As he lay there, all he could see was the blue, cloudless sky – no treetops, no horizons – only the emptiness of eternity, the place a mind goes when it holds nothing. It was like being catapulted into forever. He told me he left this world as the sky embraced him and drew him up.

“I’d always known there had to be a better world somewhere, and the old woman from my dream was waiting there with her arms extended. The old woman had to ask a question, but the only one who could answer it was a spirit on the island in the lake. The Great Spirit lived there. She shouted and I couldn’t hear. So she whispered, and the Spirit answered her.

I was there. I was there with my grandmother. And I understood what she said. She called me by the name I thought I had forgotten and I know who I am now and where I come from. I could see the faces of people I knew long ago, the elders, the loved ones, returning to me as if out of the moonlight breaking on the lake. And when I asked the old woman who she was she answered and took my hand and led me into the fire circle with the others who were waiting for me to join them. We watched the embers rise up and fill the night sky with stars. She took my hand and I felt her life flow into mine, and told me we’d always be one blood.”

Bruce Meyer is author of more than sixty books of poetry, short stories, flash fiction, and non-fiction. His stories have won or been shortlisted for numerous international prizes. He lives in Barrie, Ontario.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

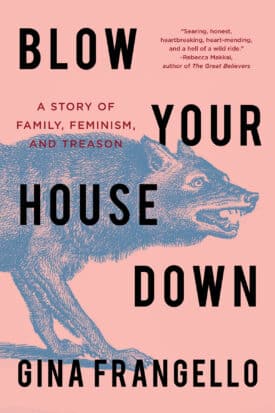

Blow Your House Down is a powerful testimony about the ways our culture seeks to cage women in traditional narratives of self-sacrifice and erasure. Frangello uses her personal story to examine the place of women in contemporary society: the violence they experience, the rage they suppress, the ways their bodies often reveal what they cannot say aloud, and finally, what it means to transgress “being good” in order to reclaim your own life.

Pick up a copy at Bookshop.org or Amazon.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~