By Gina Coplon-Newfield

My mother texted me a photo of an unfamiliar house. When I recognized the slope of the hill, I gasped with realization. My modest childhood home was gone, replaced by a McMansion.

I haven’t lived in that house for 27 years. I wish I could better trust the reliability of my memories from inside it, but I know which memories are from before and after grief moved in.

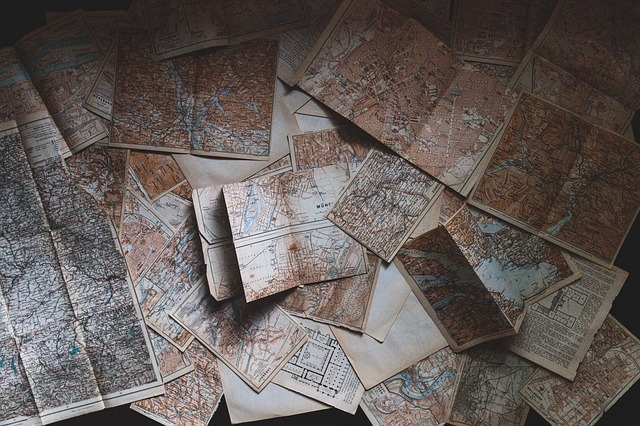

I can picture my father at our dining room table pouring over maps, trying to determine the perfect driving routes for our national park vacations. There too, he paid the bills and created my soccer team line-up. He grew up in rural Georgia in the 1950s where soccer was an unfamiliar sport, so coaching girls’ soccer in suburban Boston in the 1980s was something he studied like a new language.

I recall one dinner when my sister and I, at ages two and five, were laughing at the silly names we were brainstorming for our new puppy. My mother exclaimed with her pointer finger skyward, “That’s it, Feathers! Golden retrievers have hair like feathers.” But it’s possible I remember it that way because my mom often makes exuberant exclamations, or I’ve seen a photo of us in the kitchen that morphed into that memory.

I can summon a scene –like a movie- of Feathers sneaking into the living room, taking my dad’s wallet from the table, chewing it to bits, and looking sheepishly at my dad when he entered the room. My dad started yelling at her, but then he stopped, having realized she was just a puppy, and took her for a walk. Or at least, years later, that’s the way I told my children that story over and over when they were little. They loved hearing it. Had it really happened that way?

Memory is a curious thing.

I can picture myself at 14, struggling through a math assignment at the kitchen table. My dad urged me to approach it one section at a time rather than get overwhelmed by the entirety. I interpreted this as not just a logistical way to think, but also a calming way to feel about what I needed to accomplish. One step at a time, I tell myself regularly even now in my 40s when I’m facing a difficult work project or just staring down a mountain of dirty dishes. My dad was a psychiatrist. He likely often repeated this kind of guidance, but for some reason, I only remember him sharing it this one time.

My dad died of a sudden heart attack at age 47. My sister, age 12, and I at 15 were at sleep-away camp. Our mom shared the grim news with us in the camp owner’s living room. We screamed in horror.

When we returned home, the house felt completely different. On my dad’s bedside table, I saw Night, Elie Wiesel’s Holocaust memoir. I wondered if he had read it on my recommendation and what he thought of it. I realized I’d never get to discuss the book -or anything- with him again.

I can picture my paternal grandmother lumbering up our steps that day. I thought this is what a broken person looks like.

After the funeral, I was sitting in my bedroom with an older cousin on my dad’s side who said, “Your dad was the glue that held our family together.” I remember thinking this was the new kind of grown-up conversation I’d need to get used to having.

That week when family and friends poured into our house with food, and our rabbi led nightly services in our living room, I learned that the Hebrew mourner’s kaddish prayer actually doesn’t mention death. Rather, it describes our belief in an awesome God that makes life possible. Learning this made me feel like life was more powerful than death. Reciting the prayer felt like a small act of resistance, like I wasn’t going to let death win.

In the years that followed, the absence of my father felt like a presence just as formidable as a living person. There my dad was not at our dinner table making corny jokes. There he was not sharing the gratification of me making the varsity soccer team after his years of coaching. There he was not sitting with my mom at the edge of my bed looking at college brochures. There he was at bedtime not saying “love ya” in his southern twang. This absence of him made our house feel heavy.

The walls of my childhood home did go on to contain some joyful memories during this after period. Close friends often slept over, and we talked into the night. On my 18th birthday, my mom made me a cake topped with icing in the shape of a ballot box. At 19, I brought home my college boyfriend –now husband of 21 years. My mom likes to recount how I was trying to leave, but he said, “No, let’s have a cup of tea with your mom.” Kiss-ass.

There are countless experiences that occurred inside that house –wonderful, terrible, and mundane– that I will never remember.

In my twenties, my mom sold the house and moved to Boston with Bob, the kind man who would become her new husband.

In my thirties, I became a mom. We named our first daughter Farah, choosing the “F” in honor of my dad Fredric. When Farah’s younger sister Dori was a toddler, I was once telling her a light-hearted story about my father –perhaps the one about Feathers eating his wallet– and Dori burst out crying. She sobbed it wasn’t fair that I got to know my dad, but she never did. I was amazed that my daughter felt so strongly the loss of a relationship she never had.

When I turned 40, my high school friend Abbie flew in from Michigan to surprise me. We drove the twenty-five minutes from Cambridge, where I live now, to Lexington where we knocked on the door of my childhood home. Farah, then nine, came along. No one answered the door when we knocked, but I felt comfort knowing the house was there, the vessel of my fortunate childhood and the painful intensity of my late adolescence.

Perhaps this is why I was so affected by the photo my mom texted me after she learned from friends of our demolished house. My memories felt more vulnerable because the house was gone.

Soon before Covid-19 prevented in-person gatherings, Dori stood next to me at a friend’s Bat Mitzvah. At the end of the service, we recited kaddish in honor of those who had passed. Dori looked up at me and said, “don’t die.” “OK,” I said, tearing up because we both knew this was an impossible agreement.

With some disbelief, I realize that my daughters are now the same ages my sister and I were when our home became a house of mourning.

My husband and I, too, are about the same age my parents were when my dad died and my mom became a widow. I am nearly the age my mom was when she successfully, quickly fought off uterine cancer, avoiding the early death my dad could not escape at so-called middle age.

I worry my kids might experience loss like I did, aware that life can be taken or not taken at any time –by the likes of a heart attack, cancer, or a pandemic. All we can do, of course, is treat life as a gift, though sometimes that’s hard to keep top of mind.

I wonder which memories of joy and pain my children will keep from our house as they get older. I am realizing each memory is not a solid thing, but rather something re-shaped, lost, or cherished over time.

Gina Coplon-Newfield is an environmental and social justice advocate. She has published a case study about environmental advocacy with Harvard Law School, written many recent blog articles about clean transportation issues, and is quoted regularly in the media in such outlets as the New York Times, Bloomberg News, and Politico. This is her first venture into writing a personal narrative for a public audience (since a few overly serious poems in college). She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts with her husband and two daughters. She can be found on Twitter @GinaDrivingEV.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

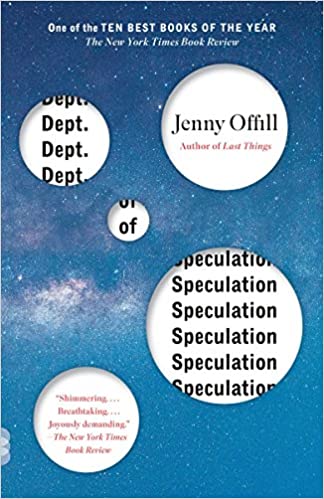

Although each of Jenny Offill’s books is great, this is the one we come back to, both to reread and to gift. Funny and thoughtful and true, this little gem moves through the feelings of a betrayed woman in a series of observations. The writing is beautiful, and the structure is intelligent and moving, and well worth a read.

Order the book from Amazon or Bookshop.org

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~