by Alexandra Steffgen

“Take me somewhere beautiful.” I requested of Sour, my dear friend and favorite tuk-tuk driver, one September evening. I was desperate to shirk my responsibilities for the next few hours in search of a different perspective. Earlier that day I’d walked through the school doors, and braced myself in the air-conditioned teachers’ lounge. I’d stood in classrooms with boarded up windows (the school director thought views of the busy street provided too much distraction), I’d fought to raise my voice above the ricocheting whispers, and assuaged the restlessness of the second graders with a word search puzzle. After four hours, I’d set out toward my second job, onto the uneven sidewalk where bits of jungle reached through the cracks, past pop-up restaurants and tuk-tuks hung with hammocks. I’d walked into the choking, melting heat, alongside the swerving, droning traffic until I’d reached the Greek restaurant. There, I’d changed out of my sweat-stained shirt and skirt, straightened the tables, and joined the kitchen ladies in the attic for salty kor stew. I’d watched as tourists passed under our electric blue awning, served them when they came in. When the boss, a tall Turkish man twice my age, stopped by, I’d swallowed as he told me, “You look like a sexy secretary in those glasses.”

When I finished my shift, I fought the urge to return home, knowing my boyfriend was probably sitting in our garden, getting stoned and drinking beer. I knew that the tension between us was drawn so tight that any wrong move would cause it to snap. Life was weighing me down, and I needed to be reminded of why I had forsaken a college education, a life in the US, to be an expat in Cambodia. I needed to be relieved from having to be strong six days a week, while I worked two miserable jobs that barely paid enough for me to afford rent and a frozen margarita on my day off. I needed to forget that my relationship was precariously balanced, that the thought of breaking up and having to make a new home by myself in a foreign country as a 20-year-old made my stomach hurt. I needed to be coaxed out of the confines of my mind.

Dust lifted at the sides of the tuk-tuk as Sour swung onto a red dirt road. The concrete of the city gave way to unruly foliage, splayed out palm trees, plots of land where kids played soccer. Trenches by the sides of the road revealed lounging water buffalo. A sinewy cow passed by so closely that I had to jerk my hand back from the armrest. The road came to an end where the flooded rice paddies began, and a row of wooden huts formed a barrier between land and water. Locals sat on overturned boats and reclined in hammocks, snacking on rice and crunchy shrimp cakes. They turned to look as we pulled up, and I could imagine them thinking, “Is that a barang, a white person?” Half-naked kids raced into the flooded rice paddy, seeking relief from the sticky warmth of the day. To our left, dark clouds gathered and spit out rain on the fields below. To our right, the sun shone. Two rainbows ran down the middle.

“This ok, Sister?” Sour turned around on his bike. “Perfect, Bong.” I answered, using the respectful word in Khmer for an older friend or relative. The languid locals, the double rainbow, the greens and blues and reds around me, they provided just the right dose of awe to pluck me from my inner pains and plant me right down in the presence of the evening. Sour stuck a thin cigarette in his mouth and approached a family sitting nearby. The woman threw her head back to laugh at something he’d said, her kids prodded each other toward a stand that displayed sugary snacks. I took a deep breath, craving the sense of abandon I’d felt on many of my travels. “Should we swim?” I asked Sour. Without waiting for an answer, I kicked off my flip-flops and waded in.

The mud was slimy under my feet, so I dove under, letting my own momentum carry me through the lukewarm water until my lungs begged me to resurface. Swimming had always brought me peace. As a kid, I’d spent my summer days splashing around in lake near to my house, emerging shivering and prune-y, hair plastered to my head. Sometimes when I couldn’t sleep at night, I’d imagine I was plunging into a clear blue lagoon, letting the water relieve me of gravity’s pull, relieve me of the pull of human life. Sour took off his shirt and joined me. We got up the courage to plant our feet in the slippery mud, then watched the rainbows shimmer and taunt us with their ephemeral beauty. Sour took a photo of us, smiling with the joy of unplanned fun, a reminder that we were very much alive.

When I finally trudged to shore, the white and black striped skirt I’d worn to school showed no signs that it had once been white, my shirt dripped water the color of coffee with cream. I wrung out my clothes and enjoyed the breeze through their dampness on the ride back. At that point the sun had eked out its last rays, and the first stars appeared through the smog. Calm spread from my heart out toward my fingers and toes. As we rode, my clear mind began to sneak back to its darkest corners. I imagined the conversation my boyfriend and I might have that night, the look in his eyes when I told him about this outing. Suddenly, an image appeared, as if it had been dropped into my head. I was swimming in a river with my boyfriend, looking up at looming mountain peaks, letting the current sweep us along. Maybe it will all be ok.

That night, seated at our picnic table in the garden, watching the geckos shimmy up the doorframe, I told my boyfriend about the vision. “Usually when I see things like this it’s showing me the future. We will be together somewhere like that, I believe it. And I hope for it.” He scoffed and looked over my shoulder. “So we’re supposed to stay together just because you dreamed it?” Lying in bed a few minutes later, in the thin stream of air coming from the AC, I imagined I was diving back into the muddy water, shedding the gravity of the day, the gravity of the conversation.

Often the biggest moments in our life are disguised. They enter, seemingly innocuous, then prove to be earth-shaking. At least that’s what I would come to believe a few months later, lying in a hospital bed with an IV leaking into my arm. The words of my doctor in the US echoed in my head. For someone with Cystic Fibrosis, staying in Cambodia is, frankly, crazy. You picked up an E. Coli sinus infection from a flooded rice paddy, and you will only come down with worse. My boyfriend and I had broken up the night after the swim, in one of those fights that seems to escalate in slow motion, then suddenly explode, sending us careening towards the end of the world, then fizzling out in stony silence. With the help of friends, I’d moved into my own apartment, where I could shut the door on my adult burdens and dance with my solitude. Those same friends offered me temporary jobs, gigs that would pay the bills and allow me to escape from the misery of teaching and being underpaid by a creepy restaurant boss. With some distance from my former pains, I sought to make the most of what I’d soon find out would be my last months in Cambodia.

Two years later, that same boyfriend and I sat on the banks of the San Miguel river, except this time as husband and wife. The memory of him showing up at my apartment and falling into my arms, the memory of his promise to stick with me through my sickness, of his decision to sell his business, of the discussion on the plane flight back to the Western world with all our belongings in tow—they were all faded now. We had long since shed the gravity of my infection and the infusions in the local clinic, the flights to a hospital in Bangkok, the slow deterioration of my body, for a lighter reality. Outside the courthouse in the small ski town where we made our next home, we had promised to love each other forever. Then we’d sought out a private spot on the river, a place to sit and read our vows. Our silence now meant that we were both thinking of Cambodia, aching for it. We watched the swift current swirl around silvery trout. Rust-colored hillsides, dancing aspens, and craggy mountain peaks blurred on the surface of the water. And all the reds and greens, the blues and silvers, provided just the right dose of awe to pluck me from my inner pains and plant me right down in the presence of the afternoon.

Zanny Steffgen is a young woman who uses writing to explore her transition from life in the US to expat life in Cambodia, then the jarring return to the Western world. Her travel essays have been published on The Mindful Word and Verge Magazine, among other publications.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

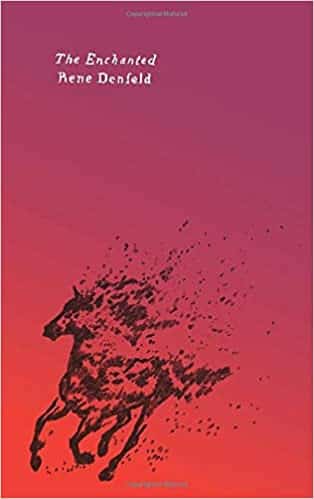

Margaret Attwood swooned over The Child Finder and The Butterfly Girl, but Enchanted is the novel that we keep going back to. The world of Enchanted is magical, mysterious, and perilous. The place itself is an old stone prison and the story is raw and beautiful. We are big fans of Rene Denfeld. Her advocacy and her creativity are inspiring. Check out our Rene Denfeld Archive.

Order the book from Amazon or Bookshop.org

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~