By Jillian Schedneck

At 21, it was stomping through the streets of Bath under a perpetual pissing of rain, reading the obscure poetry of Anne Finch and Lady Mary Montagu, hanging around pubs in between class waiting for English men to talk to me. It was liking myself more than I ever had before. I had left Boston a shattered, friendless virgin, but after only a few weeks in England, I was rapidly turned into someone new: a version of myself I’d only dreamed of. I spoke up in class, made my new friends laugh, and managed to capture the attention of English men, at least for a little while. And this was only the beginning.

I fell in love with waking up in Bath, blinking into the light from my bedroom window. I fell in love with ravenous lunches of Cornish pasties or brie and ham sandwiches, sitting on a bench in the Abbey Square with my knees pulled up, a book resting on the curve of my thighs, listening to the clipped accents of tour guides. I fell in love with Great Pulteney Street, a long stretch of limestone colored terrace houses that I liked to imagine myself living in one day.

My body felt different, lighter, as if I stepped on springs, as if the great knot of tense energy that had once existed in my chest was now unraveling. What had taken me so long to get away? After all, I stood on the same earth, breathed the same air, and lived by the dictates of the same sky. And it was so much better here; more than that: it was as if life, my now luminous life, happened only here, and the rest—before and after—could only be grey, dull filler.

Strolling the streets of Bath, I saw myself following in the footsteps of the eighteenth century women writers I’d so admired last semester in my survey of British literature course. I had improbably recognized myself in these women—countesses and literary hostesses, austere wives and the scandalously single—and their struggles to write. I hadn’t read Alexander Pope or Samuel Johnson in this personal way, but as old men in wigs, penning polemics that never stuck with me. But when I came to those women’s poems and diaries, I wondered, what would I have done in their places? If writing meant I would likely appear foolish and incompetent in the world of men, would I have had the courage? I didn’t think so.

That unnamed fear nettled me, made me pause and finally decide that on this fleeting, life-altering study abroad, experience was key. I had to gain that courage. In order to create worthwhile stories, I told myself I needed the insight that come from chance encounters, longing and love. And I wanted to see my see my transformation in the eyes of another, this new version of myself reflected back at me. So one night, when an older man asked if I’d travel to Barnstaple with him the next day, I said yes.

He approached my friends and me as we sipped black ciders at our local pub. “Smile for me please, ladies!” I squinted up at him and flashed a smile.

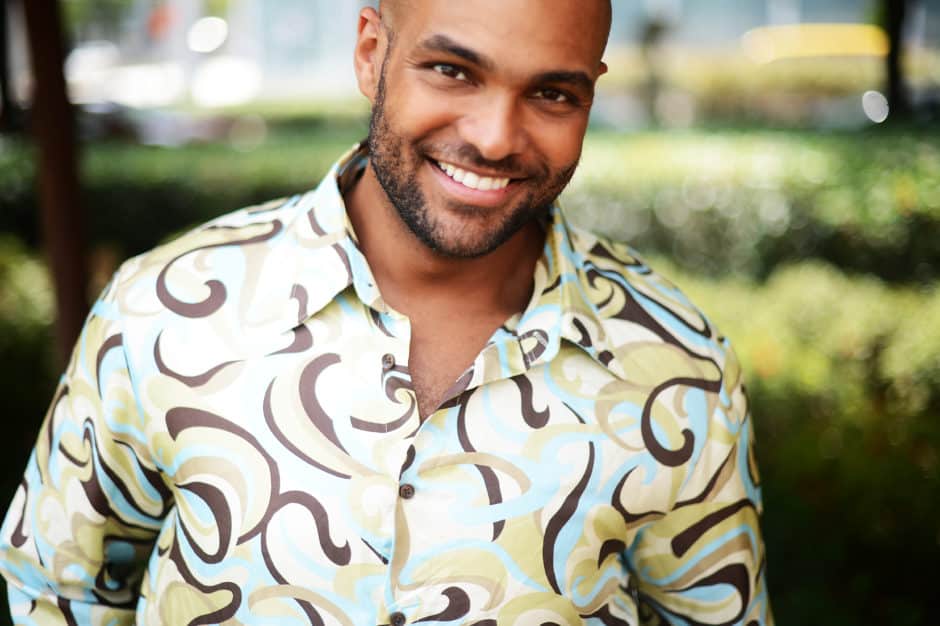

He was in his early thirties, barrel-chested, with hazel eyes and thick lashes. “I thought so! You are American. I had a bet with my mate.” I glared at him, confused. “Because you all have perfect teeth! Most of us English haven’t been so fortunate.” He let out a roaring laugh. I was the only one to join him.

My friends quickly found other men to talk to, and soon it was just the two of us. Aaron didn’t ask me the usual: how long I had been in England, my impressions so far, or where I was from in America. Instead, we made fun of each other’s accents, sang along to cheesy pop songs playing in the pub, and ordered several more rounds. I learned he was a regional salesman for LazyBoy furniture, and when I said I was studying eighteenth century women writers, he looked at me with a kind of wonderment.

After half an hour of chatter, he put his hands on my shoulders. “Listen, I’m going to Barnstaple tomorrow for work, so you might as well come along. See a bit of the country while you’re still here.”

I took a step back. Was he serious?

“Don’t you fancy me?”

“I don’t know!” I shouted. But I did like the way he was looking at me, determinedly, willing me to fancy him. “Ok,” I said, figuring simultaneously that this was just the kind of invitation I was hoping for, and that I could change my mind in the morning. “I’ll go.”

“Brilliant.” He grabbed my waist. “Can I kiss you?” Then he leaned in, soft lips on mine, hands pressing into the small of my back.

The next morning, I couldn’t work out if I was being romantic and adventurous, or insane and duped. But he exuded a kind of light, an effervescence. I liked it. Why make things complicated? I nearly skipped down the steps and waited outside in the bright, fresh morning for Aaron to pick me up. Wearing the new red coat I had bought in London, I felt pretty, magnanimous, in love with the turn my life had just taken.

A white hatchback slowed and then stopped. Aaron stepped out of the car, handsome in the daylight wearing a dark grey suit.

“Happy to see me? Or do I look too old for you now?” He said, squinting at me.

“You look fine,” I said, rising and walking to the car, and then worried that sounded wrong. “Good!” I shouted. “I think you look very nice.” Aaron laughed as we got into his car and gave my thigh a big squeeze.

Then he tossed a spiral bound book of road maps onto my lap. “You’re in charge of directions.”

For the whole day, we drove around the English countryside, visiting quaint towns. His job seemed cursory and cruisy. He checked in on furniture stores nearly as an afterthought. Aaron even made a house call, fixing an ailing chair in an old woman’s living room. Throughout the day, I learned that he was thirty-one, a vegetarian, and, crucially, that he lived in a flat in Great Pulteney Street. I couldn’t believe he lived on the most beautiful street in the world and he wasn’t even famous.

By the time we got home that evening, the sky was deep pink and the sun was falling beyond clusters of brown roofs. I wished we could remain just like this: anticipating our entrance to the stunning city below and marveling at the night ahead. A great sense of possibility overwhelmed me, and I saw myself following in the footsteps of some of those bold eighteenth century women writers, Hester Thrale and Lady Mary Montagu, who wrote diaries and letters about choosing love that would defy their worlds. Like them, I was a woman who could fall in love deeply, recklessly.

“I never want to leave here,” I said.

Aaron glared at me, his hands perfectly still at the wheel. “You can stay with me.”

And so I did. Even when I cooked at home with my roommates or went out for pizza, Aaron would pull up at my corner of North Parade when I was through, and we would travel the short distance to Great Pulteney Street. It was always a relief to slip into his car, his green eyes flashing, his laughter booming.

We spoke of a life of travel. Aaron wanted to take me to the Canary Islands, Majorca, the Maldives, places I had never heard of. For my graduation, he said we would ride the ferry over to Calais, in France, and drive through Belgium, Germany and Holland. England suddenly seemed so ordinary.

When the semester ended, we had a tearful goodbye at Heathrow airport. But I saw Aaron a few months later, when he visited me in Boston that summer. Suddenly there he was, my connection to Bath, the embodiment of my transformation into someone desirable and worldly. While lazing in the Public Gardens, we solidified our plans: I just had to get through my senior year at Boston College, and then I would move into his flat in Bath. It sounded like a dream, to live on Great Pulteney Street, to wake in Aaron’s apartment every morning and take ruminative walks in Victoria Park with notebook in hand, teaching myself to write a novel.

When the new semester started, Aaron and I emailed and talked on the phone regularly. What in the world did we tell each other? The papers I wrote, the dramas of my roommates? Footy scores and his loneliness without me, driving through the Southwest of England alone? He went for broke on calling cards and visits to Boston, and paying for my flights to England. I was continually elated that someone who lived in Bath wanted me to return there as badly as I did.

Did I mention he was barrel-chested? A big frame, overweight: fat. Even now I cringe at the word. On his first visit to Boston, my twin sister wondered what I was doing with him. Her gay best friend sneered and asked why I was with a fat guy.

“He’s not fat,” I replied, exasperated. But he was. He was vegetarian, but not the kind who ate tofu wrapped in lettuce leaves. He consumed cheese and onion flavored crisps, pasta and pizza and veggie burgers with plenty of chips. He purchased a can of Coke wherever we went. His only exercise was a jaunty walk to the service station to pay for petrol. But I never tried to change his habits. I could overlook anything when it came to Aaron.

He was my first. We had sex on his first visit to Boston, on my summer sub letter’s bed, to the background rumble of the T on Commonwealth Avenue. I wasn’t very impressed with the whole thing, and just happy to get it over with. I figured we wouldn’t have to do that again for a while. But of course, it was only the beginning.

I woke to his entreaties for sex one morning in Spain—a trip we took just before my graduation. He told me to stop checking my emails and become more dedicated to our sex life. I was waiting for notification of a writing award from my university, and had begun to correctly presume that I hadn’t won. I wasn’t like those 18th century women writers—Hester Thrale, Lady Mary, or Anne Finch, and the many others I had admired. I wasn’t gutsy or talented. I didn’t have a vision that went beyond my years, let alone my century. I hugged Aaron and said I would do better. My chance encounter, my longing and love, had achieved the opposite intention. Instead of increasing my courage, I decided that Aaron was all I had.

That spring, I bought a one-way ticket to Bath. It seemed inevitable, the fruition of my worldly transformation, and my lack of any other plan. I didn’t envy my classmates and all their worries about jobs and moves after graduation. They were only staying in America, and their concerns seemed so small. I convinced myself that I had everything sorted for a life of love and adventure abroad. Once I got on that one-way flight, everything would truly begin.

Yet something twisted inside me as my roommates spoke about their nascent careers. In contrast, I imagined my post-graduation life, spending every day with my fat boyfriend in his small, drafty flat. I wouldn’t have a job; I hadn’t even organized a work visa. My favorite professor encouraged me to approach a local US newspaper and write a column on my life in England, but I couldn’t imagine who would want to read about my cruisy life in Bath. I began to envision my immediate future as a failure, trudging around Bath alone, totally dependent on Aaron: financially, emotionally, socially. This dream life I had concocted suddenly seemed utterly boring and unproductive. It became crystal clear that this situation was intolerable.

Still, I hesitated putting this decision into action. Quite frankly, Aaron had spent a lot of money on our relationship, and I felt I owed him for that. But what did I owe him exactly? Another year? A few months? The idea of translating his financial investment in our relationship into days and weeks began to seem so preposterous that one night, a few weeks before my flight to England, I called Aaron to say I wasn’t coming. I didn’t think I would actually do it until I had dialed his number and said the words: “I’m not getting on that plane.”

I was back at my mom’s condo in New Hampshire by then, suitcase open in my old room, filled with the clothes I had planned to take to Bath. Aaron pleaded with me to use my ticket, promising to buy my return flight whenever I wanted to leave. But I couldn’t. I couldn’t go to Bath and then leave again. If I went, I would end up staying.

I cried for a few weeks, and then moved back to Boston for the summer. I spent my days waking at 530am to work the early shift at Starbucks, taking afternoon naps in the Boston Commons, and dating a sweet guy who showed me what great sex really was. When the summer was over, I moved to London on a student-work visa with my friend Katie, a wonderful girl I had roomed with in Bath. I got a job editing ad copy in a poorly lit office. Katie and I went out every night with the aim of finding British boyfriends. We found a few. But for me, Aaron was always in the background. I met him all over England, wherever he was headed for work: Nottingham, Brighton, Dorset.

On the trains to meet him, I would take out my notebook and write about the surprising pleasure of looking for a London flat, visiting all those otherworldly pockets of the city and imagining my life in each one. I wrote about the guys I kissed in bars. When they asked me to come home with them, I would just laugh at their proposals, because I had only slept with two people and the idea of having sex with a near stranger seemed hilariously preposterous. I wrote about how different it was here than in Bath, only a ninety-minute train ride away. Those trips, watching the dark English countryside zoom by as I headed toward the first man who ever loved me, are still the purest memories I have of the thrill of writing.

Whenever I arrived back in London after another weekend with Aaron, I would remind myself that this was the grand city of pleasure, enchantment, temptation and vice from the eighteenth century novels and plays I had studied. This had been the glittering, magical world of gardens and palaces and concerts, beautifully attired young people dancing at assemblies under golden lanterns, strolling arm in arm through the mall in St. James Park. This was where the women writers had lived, where they wrote their letters and diaries, treatises, novels and plays, and this was where they had fallen in and out of love. This was that same chaotic place where Katie and I had arrived, jetlagged and useless, where we had gotten our laptops stolen in the first flat we rented, where we shared a two-pound kebab sandwich every night. Our lives in London were neither enchanted nor disappointing, but real, and I was grateful to be there, with or without Aaron.

The last time I saw Aaron was three years later, when I was twenty-five and in graduate school in West Virginia. On my way to a summer course in Prague, I flew through London. He picked me up and we travelled to Cornwall for a few days. Even though he had moved out of Bath by then, I still fell in love with him once more as we strode through the streets of Newquay and ordered a pizza. It had been four years since we first met, and already that person reflected in Aaron’s eyes had changed dramatically.

I was no longer dependent on him for my connection to the wider world; he no longer served as a reflection of my worldly transformation. In a few years, I would move to Abu Dhabi for a teaching position; I would write a book about my life there. At 30, I would move to Australia to do a PhD in Gender Studies, and fall in love with an Australian man. All of this was ahead of me, and when I looked into Aaron’s eyes I saw a love for the soggy streets of Bath and the old dream that that would be enough.

Jillian lives in Adelaide, Australia with her husband and daughter. She runs the travel memoir writing website Writing From Near and Far, and is the author of the travel memoir Abu Dhabi Days, Dubai Nights. She holds an MFA in creative writing and a PhD in Gender Studies. Her writing has appeared in Brevity, Redivider and The Lifted Brow, among others.