1. A DAY AND YOUR LIFE IN BETWEEN

The changing colours of the sky. The fullness. And yet, more to the point, the emptiness of what seemed to stretch over us from the moment I found out. It’s somewhat scrambled – the specifics of how your news reached me. A phone call, I’m pretty sure, from Kim in Adelaide, South Australia, calling to tell me in Ohio, North America, that you had died. That you had died of AIDS. And yet you’d never whispered a word to me that you were ill. Did I scream? Possibly. I’m sure that I cried out, and cried copious amounts while skating hell for leather on my roller blades past the bewildered, sometimes plain terrified faces of pedestrians who fled from my flaming eyes, as I blasted U2, Sinead O’ Connor, The Eurythmics, George Michael and Janet Jackson into my ears from a cassette-playing Walkman in my fanny pack, through a violence of hot pink headphones.

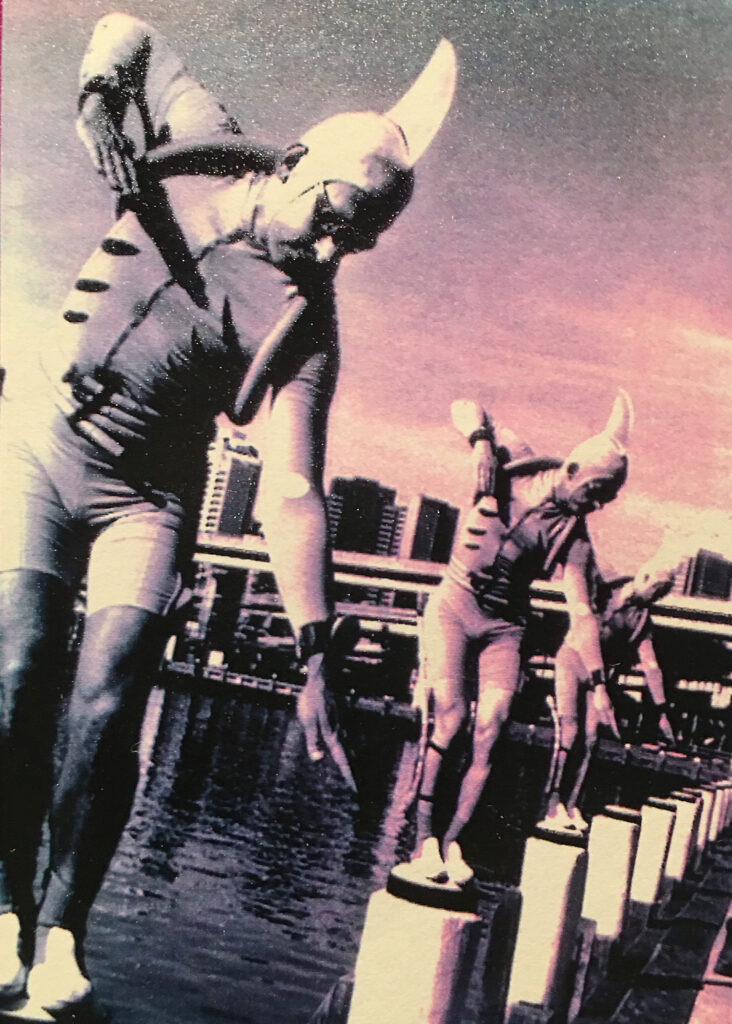

Columbus, Ohio. I mean really. We’d been confined there for an entire month, appearing as our performance art trio, Chrome, at Ameriflora – a sprawling, gigantically mainstream flower festival where, usually, audience mouths fell agape from the moment they saw us. Because there we were: three athletic young men dressed in tight, turquoise blue wet suits with black trimmed gills ‘n all, helmets with shark fins protruding from our heads, and wraparound mirror eyewear that discretely enabled all three of us to move in synchronisation. Plus we sang a capella harmonies; songs about sand and the sea and sunshine and surf. Or played our aqualung tube belt-harnesses as saxophones and didgeridoos while ringing bicycle bells or clacking castanets. So when someone would gawk and shout, “Oh my God what are they?! Ray-Shelle! Git’ yer ass over here – these Disney characters are SO weird!” – I had to forcibly stop myself from snapping back: “We are highly trained professional performers you git! After multiple years of hard work, dedication, rehearsals and run-throughs, we’ve flown half way around the planet to bring you this unique and frankly, really expensive show. So please Fuck Right Off with your Huey, Dewey, and Louie blasphemies!” Fortunately, we had a song in our repertoire entitled “Looking for Nirvana”, so in such desperate moments as these, we could always switch to that for a soothing, calming balm. And usually, I did.

But oh the absurdity of the American Midwest, to outsiders. I was so desperate to get out of there and back to what had now really become home: the Lower East Side. The point being though – you would have understood! All of it! Your love of New York City had helped carry me there in the first place. So, the sweet relief I was anticipating, of getting back to the Ludlow Lounge, my beloved, ramshackle, Ludlow Street loft I shared with a rotating crew of friends. That would be peace and joy in itself right away, but after dropping my bags I would certainly duck out to El Sombrero, our dodgy Mexican restaurant downstairs, to pick up one of their infamous frozen margaritas to go, run back upstairs to kick back on one of our street-rescue couches, or nestle in some shag pile on the mezzanine, pick up my clunky black bakelite phone, and rotary dial YOU, Ian! You a day ahead of me in Australia to tell you everything, to tell you all of this and so much more, so no, no fucking no! You simply canNOT be dead!

2. CLINGING ON

As I look around me I see all of us artsy folk, the chosen family members who have come to be in this room for Eric in his dying moments. It’s New York. It’s 1991. And again, it’s AIDS. Eric’s mother is here, fresh off a ‘plane from Paris, bearing violets that apparently were covered in dew drops when she plucked them from her garden that morning. While weeping and sobbing she proffers their long-haul-flight wilted remains, time and again to the skeletal figure before her, sunken so far into his bedsheets it’s getting difficult to discern his presence any more.

Eric’s father sits in a corner, staring into a place none of us can see. He’s a Seventh Day Adventist elder who refuses – no matter how much the rest of us entreat him – to approach his son. Or touch his son. Or say goodbye to his son. We beg and plead, now with tears flowing as well. When, some hours later, Eric finally dies, his father remains frozen in place for it’s-hard-to-tell how long. Until, at a random moment without warning, his ice suddenly cracks – only the precise amount necessary for him to stand. Wordless and expressionless, he then exits.

The rest of us, all of the pagans who remain, solemnly agree to pray that some god or goddess, from no matter what respected religion, or random branch of belief – that some entity, anywhere, will try to rescue this man’s soul. Otherwise, how on earth will he live with himself, let alone his wife and others, for the remaining days, weeks, months or years of his faith-full life?

One by one we bow our heads, bid Eric adieu, and quietly depart. We leave Sean, Eric’s boyfriend, to take as much time as he needs, alone. And then, just as quietly we all wait out in the corridor, to do what we can to pick up and put back together Sean’s broken pieces.

3. IN THE FALLING SNOW

The night Chad died it snowed. In fact it had already been snowing for several days, so Manhattan had taken on that special kind of quiet that tends to come about during heavy snowfalls. Plus, it was the few days directly after Christmas, so the city’s chaotic December madness had finally subsided. He was in St Vincents on Fourteenth Street. Of course many gay men at that point had died of AIDS in that exact same hospital, but that was largely in the decade and a bit before then. Now it was 2002. This shouldn’t have been happening. People weren’t dying of AIDS any more, and yet there was Chad, disappearing over the weeks and months leading up to this, right before our very eyes.

His sister Stacy, his Mum Evelyn, and myself were there for him, plus many other friends who came and went. But it was the three of us who took it in shifts to stay in his room, curled into an armchair or propped awkwardly into an icy window sill, just to be there for him because there weren’t enough nurses to care for all the patients. An endless cavalcade of doctors and specialists paraded in and out, all assuring us they could (and definitely would), save him. The night we had admitted Chad, many weeks prior to this, I promised him I would do everything in my power to keep him alive slash save his life if necessary. But then he lost his speech. And not long after that his sight as well, rendering him unable to write. Which meant we lost the majority of ways of communicating with him, even though he was palpably still there in front of us. Which meant we then said yes to diabolical things. Because they would save his life, remember?! So… once Chad could no longer swallow and the doctors said we need to put feeding tubes directly into his stomach, the three of us said okay. But was that right? And when they said we need to drill two holes – large, wide ones – into his skull so we can administer the chemo directly, the three of us said okay. But was that right?

We’d made his room so beautiful and peaceful with soft music and flickering Christmas lights that nurses often asked if they could linger a while – they loved the energy we had created so much. Until one night, feeling conflicted in my desperation, I ambushed one of our favourite nurses out by the elevators. It was perhaps four in the morning – she was about to head home from her shift and clearly I startled her. “Could you please just tell me straight up whatever it is the doctors are not telling us?” She placed a kind hand on my arm as she shook her head, gravely. “I’m so sorry. Best prepare yourselves. We don’t even think it will be long now.” And it wasn’t.

Within 48 hours, Chad died. Once Stacy, Evelyn and I turned away from his body for the final time, after collectively agreeing that his spirit had already vacated the terrifying corpse he’d left behind, I walked home slowly, carefully, across downtown, in the falling snow. There’d already been so many tears leading up to this that now I was overcome with a new kind of quiet, and a new kind of regard for every single one of my footsteps that left fresh snow-tracks, witnessing my passing. And gradually it dawned on me that for every single one of my friends, no matter where in the world they were at that exact moment, I could ‘place’ them on a vast geographic, locational kind of mind map. But the one I was closest to, within a trifling total number of footsteps, I could no longer place, anywhere. He’d transcended every map I’d ever seen or could imagine. Which is when I learned for certain that Chad was no longer in the hospital room behind me – he was with me. He was everywhere, surrounding me. Forever in the falling snow.

CODA: What a privilege it was and, twenty three years later still is, to feel his snowflake presence.

*Pictured in b+w: Chad Courtney, Matthew Curlewis, Michael Fischer, early 2000s. Michael also died, in New York, not many months after Chad – killed outright in a rollerblading accident. Why perhaps was this photo,initially, triggering for me? As palliative care consultant (and my dear friend) Cy O’Neal helpfully pointed out: “You’re next!”

***

***

The ManifestStation publishes content on various social media platforms many have sworn off. We do so for one reason: our understanding of the power of words. Our content is about what it means to be human, to be flawed, to be empathetic. In refusing to silence our writers on any platform, we also refuse to give in to those who would create an echo chamber of division, derision, and hate. Continue to follow us where you feel most comfortable, and we will continue to put the writing we believe in into the world.

***

Our friends at Corporeal Writing are reinventing the writing workshop one body at a time.

Check out their current online labs, and tell them we sent you!

***

Inaction is not an option,

Silence is not a response

Check out our Resources and Readings