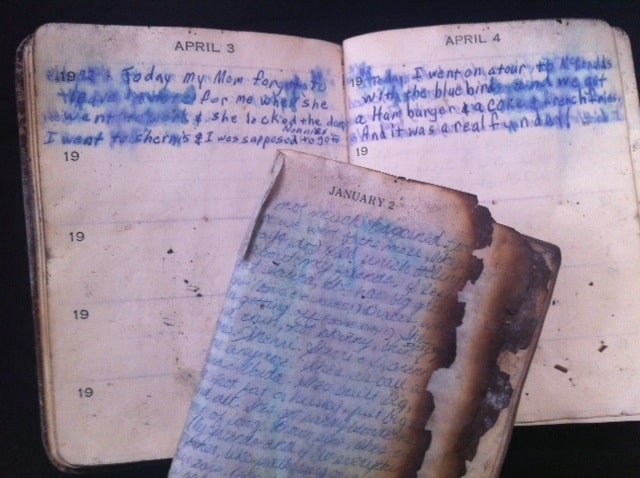

When our house burned down in 1994, all three levels burned to the ground. There was not a trace left of the sofa, the dining table, the piano. And yet, my husband, wearing thigh-high fishing boots, dug through piles of rubble four-feet deep and pulled out small blackened squares. They looked like charcoal briquets, but they turned out to be my childhood diaries. One of them used to have a Holly Hobbie cover and a little gold key attached.

I’ve kept a diary since I was in the second grade. This might have tipped me off that I was bound to become a writer. It was important to me then to document my comings and goings, important to me that someone knew I had woven straw placemats at my Campfire Girls meeting, or been chosen third for the kickball team at recess. Someone beside me had to know, and so it was my diary that became the witness to my life.

In addition to my diary, I’d taken to walking around town with a mini Hello Kitty notebook in the pocket of my plaid Dittos hip-huggers, in case I felt a sudden urge to write something down.

Nine was a heavy year for me. A lot of things went horribly wrong in our family life, and then my mother sent me away to live with my aunt because, on top of all the drama in her own life, I guess she couldn’t handle a suicidal kid. I hadn’t meant to cause her trouble, but I had meant to walk into oncoming traffic on that main boulevard. I didn’t plan it. I was numb and sort of floaty, almost like I’d just checked out of my body and then whoosh. The slamming of brakes. The honking of horns. And before I understood what had happened I was living somewhere else. The only thing I did understand was that my mother had abandoned me. She had broken my heart.

A few months later, on a fall day, I took a long walk by myself, letting the thoughts and memories of the “traffic incident” and the reasons that drove me to the street that day rattle around in my head until I was exhausted. I slumped down onto a curb and took my Hello Kitty notebook out of my pocket. I began with my stepfather “Bullet,” the domestic violence, the drinking and drugs, then the next guy who left us, and the next guy, and the worst one – the drug addict with the gun fetish, and finally losing our home and having nowhere to go. I wrote and wrote and wrote until I poured it all out of my still-forming, rapidly beating nine-year-old heart.

When I finished, I stared across the street at a rock wall surrounding the perimeter of an apartment building, huge and imposing. The people who lived behind that rock wall must have felt safe, I thought. I folded up my notes, one by one, and stuffed them into the crevices between the rocks in that fortress wall until they were all gone, and then I prayed that somebody would find them. Even if it was one hundred years from now, I wanted someone, even one person, to know how I felt. I wanted someone to know that usually I was picked last for kickball but once I was picked third, that before I fell asleep at night I sometimes held my breath until I fainted, and that the girl who walked into traffic on a main boulevard had survived and was still here to tell the tale on this Hello Kitty notepad.

In a way, I think I set my future in motion with that very small revolutionary act. I was raising my voice, and acknowledging that my story mattered, even if it was a very small story on very small chits of paper. Decades later, those and many other journal entries made it into the pages of my first memoir, and into the one I’ve just written, Fire Season.

My stories are all I carried with me as the ambulance drove me away from the raging inferno, my home, the place that had once housed all I thought I was. I know now that my stories are the only thing of true value that I own. No flames could take them from me. So I tell my stories, and I write my stories, and I live new stories, and I listen to others’ stories with great reverence, because I know how precious they are and how quickly everything we believe in can go up in smoke, no matter how high we build our rock walls.

And I know that no matter how far we’ve come and how much we’ve grown, we are still who we always were, the truth at the root of our very being, because here I am as Fire Season makes its way out into the world, still pouring out the contents of my fifty-one-year-old, rapidly beating heart, feeling very much like the little girl stuffing notes into a rock wall. Hoping somebody will find them.

Hollye Dexter is author of the memoir Fire Season (She Writes Press, 2015) and co-editor of Dancing At The Shame Prom (Seal Press)– praised by bestselling author Gloria Feldt (former CEO of Planned Parenthood) as “…a brilliant book that just might change your life.” Her essays and articles about women’s issues, activism and parenting have been published in anthologies as well as in Maria Shriver’s Architects of Change, Huffington Post, The Feminist Wire and more. In 2003, she founded the award-winning nonprofit Art and Soul, running arts workshops for teenagers in the foster care system. She currently teaches writing workshops and works as an activist for gun violence prevention in L.A., where she lives with her husband and a houseful of kids and pets. www.hollyedexter.net.

To get into your words and stories? Join Jen Pastiloff and best-selling author Lidia Yuknavitch over Labor Day weekend 2015 for their 2nd Writing & The Body Retreat in Ojai, California following their last one, which sold out in 48 hours. You do NOT have to be a writer or a yogi.

“So I’ve finally figured out how to describe Jen Pastiloff’s Writing and the Body yoga retreat with Lidia Yuknavitch. It’s story-letting, like blood-letting but more medically accurate: Bleed out the stories that hold you down, get held in the telling by a roomful of amazing women whose stories gut you, guide you. Move them through your body with poses, music, Jen’s booming voice, Lidia’s literary I’m-not-sorry. Write renewed, truthful. Float-stumble home. Keep writing.” ~ Pema Rocker, attendee of Writing & The Body Feb 2015

When are you coming to Denver?

Wow your words mean so much. Thank for saving them and sharing them with the world.

[…] Dexter, author of Fire Season, stopped in at The Manifest-Station to share her story about what she salvaged from the fire that destroy her family’s […]