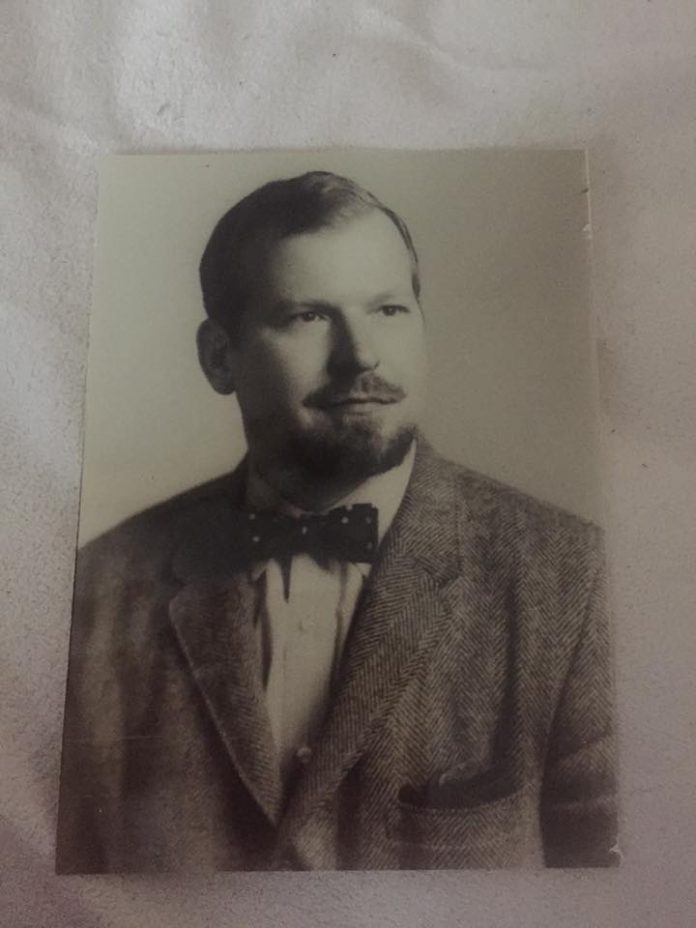

I have not shared this photo before. I have wanted to keep my father to myself, perhaps because, when he was alive, I had to share him with so many.

But it’s Father’s Day, and it is both nationally and personally a sober time. So I am giving all of us a gift by sharing my father once again.

My father left for college when he was only 16. He left for the big city from a farm in Nebraska, where he had no exposure to Black people.

There was no one whiter than my father, with his light eyes and hair, his aquiline nose, his Midwestern twang, and the way he said words like egg and roof. Tweed jackets with leather elbow patches and Oxford shirts were his uniform. He lent them a white guy cool by finishing his look with khakis and topsiders that he wore with no socks. He smoked a pipe. He loved Latin and classical music and German food. He was completely and unapologetically white.

My father was also the greatest man I have ever known. I described him to a friend recently: the way my father was committed to social justice and the cause of civil rights; the way he gave his voice, his body, his life force to the struggle for equality for Black people to the degree that he received letters of thanks during his lifetime from Martin Luther King, and to the degree that he was eulogized in Congress upon his death.

My friend said “Your father sounds as though he was very…optimistic.”

This friend of mine is a very polite young white man. I could tell from the pause between the words “very” and “optimistic” that what he’d wanted to call my father was “naive.”

Here is what my father was: he was grounded in his identity as a white man, aware of the privilege this status conferred upon him, and acutely conscious of the mantle of responsibility laid upon him to live a life of service to those upon whom society had conferred a different status entirely.

It is not, I suspect, an easy thing to be a white person and choose to live in the world this way. There are ways in which it is perceived as traitorous to one’s privileged position in the status quo. I understand this a little as someone who has some light skin privilege. White people have felt lulled, because of my appearance, into saying things they never would in the presence of someone darker skinned. And so, when I protest, call attention to racism, speak from my position as a Black person about hurt and anger and frustration of my people in these days, it is read as a betrayal by some.

I know because they will say things like “Why do you call yourself Black? You are just as much white as you are Black. What about your dad?”

Here is what I know about my dad:

- He had children who have birth certificates that had “Negro” typed on them.

- He was comfortable with his whiteness and with our Blackness.

- He lived his life like some Norse avenging angel, healing drug addicts on the street, marching and being jailed and beaten in the South; preaching a gospel of peace and power and purpose in East Harlem; giving scholarly lectures to college professors, hosting overseas psychologists who wanted to understand his work with the poor and disenfranchised.

He was never anything but white. He taught me that this was what whiteness could be. And so, he filled me with expectation, with impatience, with awareness that the way one walks in the world is as much about conscious conviction as it is about skin hue. My father was, in fact, an optimist, even in the face of all that might have made him otherwise. What purpose can possibly be served in being otherwise? How easy to give up , give in, fall comfortably back into the soft privilege of whiteness. But it all depends on whether you see it as an invitation to lounge or as a call to action. The Charleston killer saw his whiteness as a particular call to action. My father saw his whiteness as a different call to action. There are many who see their own whiteness as an invitation to inaction. They too, are choosing a side. My father was an optimist who believed good and right would win. In these times, I hold onto that optimism that is my birthright. If I have seemed insistent in all my FB posts on race, please know it is born of that optimism.

Happy Father’s Day.