By Beth Alvarado

When I was twenty years old, I spent a lot of time crying in a closet. It was 1975 and I’d just had my first child. I lived with my husband Fernando and two of his younger brothers in a small house. I cried often and I didn’t know why and so I was embarrassed about it. One afternoon when I was in the closet, I heard Fernando come home from work. “Where’s Beth?” he asked his brothers and I heard them say, “Oh, she’s probably in the closet crying again.”

Various people explained to me that I had post-partum blues. They said I was sad because I was no longer pregnant, which I interpreted as meaning I wanted the baby inside of me again. But the explanation didn’t make sense. I didn’t want to be pregnant again. I hadn’t especially liked being pregnant. The baby weighed almost nine pounds at birth, I had been slender before I got pregnant, and I was tired of carrying him around inside me.

Some weeks ago, I started seeing a therapist because Fernando had died—it had been two years—and I couldn’t make up my mind about what to do next. I thought maybe I was experiencing complicated grief, which can happen when you lose someone after forty years. The therapist explained to me that there are two major anxieties. One is separation anxiety and one is its opposite, encroachment anxiety, and we all feel both of them but to different extents.

This made sense. What sent me into the closet was encroachment, not separation. Of course, there was also the mystery of separation. I remember looking at the baby’s face and thinking, where did you come from? Who are you? Who gave you that name? Of course, I knew the answers but maybe that’s why we spend so much time gazing at our infants. We can’t figure it out, the mystery of their births. Even though we were there. How they did they go from being inside to being outside? How can they be separate people?

But who would want the baby back inside? When you’re pregnant, the baby isn’t such a distraction. He’s just there, a part of you. He doesn’t cause problems other than a little indigestion, maybe, a little difficulty breathing. You don’t have to change your life much for him, except you can’t eat raw oysters or have more than one cocktail or ride horses. (Or, in my case, smoke cigarettes or shoot heroin.)

But when he’s born? Suddenly he requires all of your attention. Twenty-four seven, as they say. The baby wanted to breast-feed every two hours. And then he had to have his diapers changed and then I had to wash his diapers and hang them on the line and take them down and fold them and put them back on him. I used to think if I could get four hours of sleep in a row I would be a new person. But who would that person be? Someone who had another child, went back to school, became a teacher, a writer? Or someone who cried in a closet and went back to drugs?

It’s the same with death, when I think about it: you have to redefine yourself in light of another person. Only, instead of wondering ‘where did you come from?’ you wonder, ‘where did you go?’

With death, there is no separation anxiety. Oh, maybe there is when you hear the diagnosis, but not with the death. For one thing, anxiety is always about the future, what you’re afraid might happen. But when you know death is inevitable or when it’s already happened, there’s no anxiety.

For another thing, the separation is just as mysterious. Maybe that’s why we use words like gone, lost, passed—they reflect the un-realness of the situation, a person disappearing. My late husband. But I had never been one for euphemisms. I knew Fernando was dead. I had been in the room as he was dying. I talked to him, I sang to him, my voice didn’t break down. But I didn’t realize dying was the end. I hadn’t thought beyond getting us both through that moment.

That moment: when what has always been invisible disappears.

You are left with the body but the body is not-him.

For a while, because he was nowhere, he was everywhere at once. The slightest breeze was his breath on my neck. If the microwave malfunctioned or if I saw a hawk, he was sending me a message. He was a constant presence in a way he never had been in life. In life, he had come home in the evenings and we’d taken care of the kids or, later, after they were grown, we’d shared a walk, dinner, a bed, but the days were mine. In life, there had always been a space between us, but now he had moved inside. The encroachment was complete. Death had not parted us.

But this is the paradox: because he was everywhere, he was nowhere. I began to miss him, his physical presence. I knew he wasn’t in the house, I knew I couldn’t see him or touch him or hear him. I couldn’t take a train to find him, I couldn’t reach him on my cell phone, not even in my dreams. Again, there was some difficulty breathing.

Where are you? I’d wonder. And why don’t you answer? And who am I without you?

Beth Alvarado is a writer in transition. Her essay “Difficulty Breathing” came out of a story-sharing party at a friend’s house; it is now part of an essay collection in progress. “Water in the Desert,” another essay about her husband’s death, recently appeared in Guernica, and she has another essay about being a mother, “The Motherhood Poems,” in Necessary Fiction. She teaches at OSU-Cascades low residency program in Creative Writing.

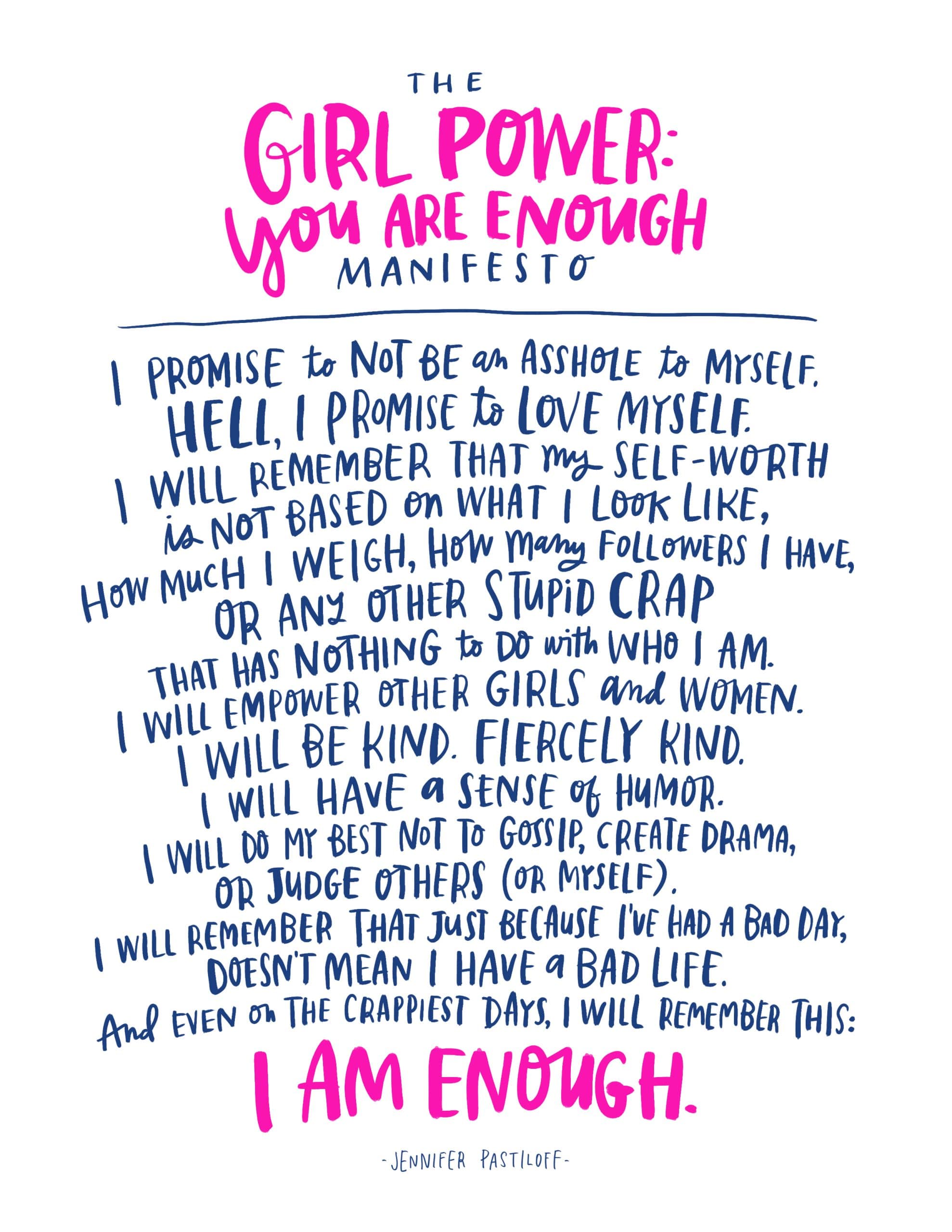

Jen is also doing her signature Manifestation workshop in NY at Pure Yoga Saturday March 5th which you can sign up for here as well (click pic.)