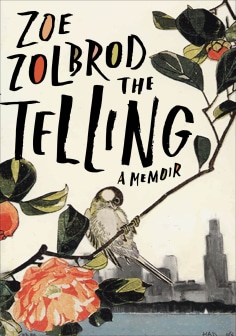

Welcome to The Converse-Station: a dialogue between writers. I read an advanced copy of Zoe Zolbrand’s book, The Telling, and I couldn’t put it down – This writing is fantastic and the book deserves the praise it is receiving. So when Maggie May Ethridge approached us about publishing an interview between her and Zoe, I was over the moon with excitement. Here is their conversation. Enjoy. xo Jen Pastiloff

When Zoe Zolbrod sent me her new memoir, The Telling, I couldn’t help but have the impression I knew what this story would be like; it’s a story of childhood molestation, and there is often a narrative that goes along with the subject. I was wrong. It’s a narrative Zolbrod has done her best to shake free of: you can feel in the writing how she again and again strives to tell the story true, tell it as it really was for her. This isn’t the same as telling something factually, of course-journalism is very different than a creative retelling of a true experience. This isn’t journalism, this is literature.

Zolbrod’s The Telling takes the reader through her experience being molested at age four by an older cousin who comes to live with the family, moving through her teen years, her twenties, and then into her adult married life as the mother of two young children. This timeline is very effective, illuminating the way that something profound yet baffling can seep into a life without overtaking it, so that Zolbrod wondered if she was over or under-emphasizing the effect the molesting had on her. This open curiosity drives many of the best passages in The Telling.

This is the subtext, the subconscious, the present and past and how they blur and move from underneath the pen that tries to press them down, the child as memoirist vs. the adult as memoirist, the way the rest of life that has nothing to do with one specific event still seeps into the picture, because nothing is life stands alone, an island, unaffected by all other choices we make. If that were true, we wouldn’t bother healing.

As I talked with Zolbrod, I reflected that often memoirs on sexual abuse are so difficult to read that I can’t read them twice. I read The Telling twice. The way that Zolbrod puts forth her abuse alongside her young twenties, alongside her adult, mother self, allows the most painful memories to have context and relevancy for her entire, empowered life as a woman, and not feel like a single knife, stabbing again and again through the paragraphs.

Zolbrod’s story is not only emotionally resonant, it surprised me as a reader by also being simply a good story. Zolbrod also happens to write sex exceptionally well, and from an empowered point of view that I don’t see reflected in our culture enough. Zolbrod unabashedly enjoyed sex, and writes with all the gusto, flavor, passion and joy of a great food writer, delightfully extolling the virtues of rolling orgasms and hyperfeminine men. Zolbrod goes after life, and you can feel this urgency in her sentences, including sex, men, female friendships, family relationships, art, literature, travel, food; we are taken along for the ride with an insightful, honest, tender yet definitely straightforward guide.

You can buy The Telling now.

Ethridge: What does your writing history look like?

Zolbrod: I have a novel that came out in 2010 called Currency. I worked on that novel over a decade by the time it came out. I’d also had a few short stories come out, and I have a MA in writing.

Ethridge: What made you decide to move to non-fiction?

Zobrod: I wrote some essays and liked writing in that form, but I really thought of myself as a fiction writer. When I started to promote Currency, I started a blog and wrote a few essays, and I found so much satisfaction in writing about topical issues and writing from my own point of view and connecting with people over my shared experience. I published some essays at The Nervous Breakdown and they had a thriving comments section and that was very satisfying…to be able to sit at your day job and connect with writers. I got more in the habit of writing personal reactions to things, and I found that I was writing often about sex crimes, because I was having such a strong reaction to them. Particularly when the crime of Jerry Sandusky was in the media, that he had abused all these boys and turned a blind eye. I wrote an essay on Jerry Sandusky and revealed in two or three sentences about my own experience…I was shaking and terrified. I don’t know what I expected, but I got incredible support. It felt ultimately liberating to say this out loud and be met with support and not scorn or disbelief.

Ethridge: What made you decide to write about your whole story?

Zolbrod: I was revisiting the material already, mulling it over, particularly some old journals. I wanted to put the energy I felt around it into a novel, and this is also at a time where I wasn’t doing very much writing because I was adjusting to parenthood. It became clear that the essays I was writing had more energy than the fiction. I was trying to code the truth, and I realized that the power was with the personal experience, and I should follow that instinct.

After that, I’d carve out time to write, and sometimes I just couldn’t. There are so many ethical concerns, so many blocks, so I spent a year or so not doing much writing at all. And then what happened, I don’t know- I just decided I’m going to do this, I have the right to do this.

Often ‘writing as therapy’ is used as description for an insult, but I think for me it actually was in some way, powerful, and I think that the writing is good, and it was very meaningful to me to be able to feel some of these emotions that are very hard. I didn’t want to dwell, but ultimately it was really beneficial to me to feel some of those emotions.

Ethridge: How did you work through your ethical and other concerns with writing about your molestation?

Zolbrod: At first I was really defensive, in particular I thought about the cousin who did this to me, and then thought about him going to prison “If you don’t want someone to write about him being a sex offender, don’t molest children” and I thought, “He’s on the sex offender registry, and that is something that anyone can find in google.” But then…it’s iffy. Other people can be implicated…I changed names, I tried not to psychologize anyone else, or assume what they were thinking or feeling, I only included things I thought were core and necessary to the core of my story. I think my biggest asset was that my father is such a generous person, and he gave me his blessing despite the fact that I was talking about some really difficult things. Things he’s not proud of or happy about- he’s a wonderful person.

I gave my father the chance to read it in final manuscript, and I told him I’d consider altering anything he couldn’t live with, and he didn’t take me up on that offer. He didn’t want to effect the editing process, and he’d deal privately with anything that would make him wince.

Ethridge: What was your experience as a reader of memoir before this? What were your influences writing The Telling?

Zolbrod: I hadn’t been a memoir reader before writing The Telling. I was probably contaminated by the view that memoirs are ‘uncool’ or less literary, which I think had effected me without doing my own examination. But as I entered this territory there were a few that I came to love, and I now I do love memoirs. There’s a lot that can be done with the form- Vivian Gornick, Fierce Attachments, was one of my early guiding lights, about her relationship with her mother. Something about it really freed me. It alternates between a more current voice and the past, which is something I do. I love The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch, I learned a lot from that, The Adderall Diaries, Another Bullshit Night In Sex City, Claire Bidwell Smith’s Rules of Inheritance, and recently I loved MOT by Sarah Einstein.

Ethridge: Did you have a plan, an outline when you began writing, or were you just writing it as it came out?

Zolbrod: I had a some kind of plan before I began writing the book…Vivian Gornick’s essay ‘The Situation and The Story’ helped me think about how to write my book. I always knew I wanted it to be a braided narrative, with several different timelines, I knew I wanted to structure it around the times I told. I felt fairly confident in the structure, it came to me, I worked hard but I never veered from the basic idea of interweaving these time frames. Trying to get the research in there, I wrestled with it a little bit. Early on I knew I wanted to include the research.

Ethridge: It was very effective, the way you used the varying stages of your life allowed me as a reader to have some kind of breathing room, so that I could read about the molesting and not feel like I had to run from the book. Sometimes books about really hard things are difficult to finish, no matter how good the writing. Your story was absorbing, had a wonderful narrative.

Zolbrod: One of the things I’ve talked about elsewhere… who wants to read about a child being abused, like you’re bringing something toxic into the world. So it really means a lot to me that you felt what I was trying to do. I want people to know that this is an empowering book, an adventure.

Ethridge: Do people reach out to you about being sexually molested after reading your book?

Zolrbod: Yes. One the one hand it makes me sad, but it is something of a comfort that I was less alone that I thought. So many of us have this experience, so few of us talk about it. It’s kind of a conversation stopper, so even if you don’t feel like you’re hiding it, there aren’t many places to discuss it. I feel badly whenever I learn that someone has had an experience like this in their own life, but also I feel a little less alone and I think other people feel less alone too. We can compare experiences, and how common thy are, feeling less isolated. I’d love for people to feel more seen, hopeful.

Ethridge: As you wrote The Telling, did you have an idea of who you were writing to?

Zolbrod: I think I wrote the book for myself, for when I used to read, looking for some reflection of my experience and I didn’t find it. I hope to offer that for someone else who might find it useful. I hoped to dispel some myths about child sexual abuse…everytime there is a case in the news, there’s so much misunderstanding about who is vulnerable, who does these things. I’ve seen in my own community when a child can spot some warning signs and know something is inappropriate and disclose what is happening before…I hope the book can aid in that.

Ethridge: Did writing about your molestation change the way you address this subject with your own children?

Zolbrod: The writing and research I did around the book affected the way I talked to my kids. Something I wouldn’t have realized, we can periodically ask our kids as part of a conversation about bodies and privacy, you can ask “Has anyone ever tried to touch you there?” Giving children an opening to say something, an opening that wouldn’t have occurred.

It’s part of our story- it doesn’t have to be the whole story.

Zoe Zolbrod is the author of the memoir The Telling (Curbside Splendor, 2016) and the novel Currency (Other Voices Books, 2010), which was a Friends of American Writers prize finalist. Her essays have appeared in Salon,

Born in western Pennsylvania, Zolbrod graduated from Oberlin College and then moved to Chicago, where she received an M.A. from the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Program for Writers. Aside for periods of traveling in Southeast Asia and Central America, she’s almost always worked full time, making her living as an editor of comic books, text books, and other kinds of books and educational materials, despite her difficulties with spelling and proper nouns. She lives in Evanston, IL, with her husband and two children.

Maggie May Ethridge is the author of the memoir Atmospheric Disturbances: Scenes From A Marriage (Shebooks, 2015), a poetic remembering of her marriage as it was before and after her husband’s diagnosis of bipolar. MME has work in Guernica, The Rumpus, Marie Claire and many others. Her novel Agitate My Heart is in last edits. You can find her at Flux Capacitor.