By Monica Drake

There’s no place more optimistic than a well-stocked pharmacy. Gleaming clean and rocking the high blast and buzz of fluorescents, everything on the shelves is there to save your life while it cushions your vanity. Crowded, tidy aisles scream, You can be healthy, strong and beautiful! When I was young enough to never need anything beyond an occasional shot of nighttime cough medicine—that sweet, Kool-Aid purple nurse in a bottle—but old enough to be out on my own, I had a job dusting cures, ringing up sales. We carried Epi-pens for anaphylactic shock, because even slight allergies can go seriously wrong. I read trifold pamphlets during the slower retail moments, making myself a student of human health. I learned that it can be the first exposure to an allergen, the tenth, or the hundredth time your body processes some unknown ingredient, in a kind of secret internal roulette, but every single second of the day there exists a slim chance: your immune system could kick into high gear and shut down your throat. It might start with an itch around your eyes or in your sweating armpits. Your blood pressure will drop, silently, and painlessly. That drop in blood pressure has the potential to undermine and weaken your brain’s decision making skills. Some people grow so cold they can’t stop shaking. It’s like a ghost has landed in their bones, when shock sets in. If you have it bad enough, your face can swell to twice its usual size. Then your cheeks sag into jowls and your eyelids get fat and you’re fifty years older than you were ten minutes before. Your skin will lump up in hives.

An allergic response can clog your lungs with fluid and swelling and then constrict your airways, cutting you off from your own life. This happens every six minutes, to somebody. If you’re fast and lucky, one jab with Epi-pen turns the whole mortal disaster around. You’ll be back in business! An Epi-pen can save your life. It’s a brilliant invention. A pharmacy has what you need.

Want to get high? It’s in the bins, drawers and vials. Time to sleep? That’s there, too.

We sold pain meds, both over-the-counter and prescription. Almost everybody is walking around in pain. That gets worse with age. I’d hum along with the Muzak and turn our inventory to face out, aligning merchandise. We had blood pressure meds, for arteries ready to burst. I’d sing to myself the new Queen and Bowie single, “Under Pressure.” Ba-da-bop-ba-da-be-dop!

Days were nice, in the pharmacy.

There were crutches, enemas, and vitamins for the proactive. We had potassium iodide tablets in case of nuclear fallout, to protect a person’s thyroid in World War III. There were scales, stocked in three different sizes: for weighing people, food portions and medicines, in a linked sequence of overeating and disease. I’d give the scales a swift, cheerful brush with the feather duster.

I earned just over three bucks an hour, the price of a discounted dime store lipstick, less than a prescription’s co-pay, and then taxes off the top of that. I didn’t mind. It was lovely work. I’d organize greeting card displays, sorting the blue and white envelopes. I’d shuffle goods on shelves and read labels, always expanding my education.

It was my third job. In high school I made get-out-the-vote calls for the Democrats, and then worked at Burger King, where I was too shy and forever at least thirty-seconds over the manager’s timed goal for building a Whopper. I couldn’t get the Whopper hand-dance down: Right hand, left hand, left, left…right? Pickles, then ketchup? I never remembered. The pharmacy was grease-free work. I counted that as a plus. It was less dehumanizing too, because I could wear my own clothes. I was clearly on my way up.

I’d feel the hard certainty of plastic containers, the sharp edges of boxes. I’d taken three high school equivalency classes through the mail over summer—Government, Food Study and Journalism. Food Study was helpful. In that class I learned that you can estimate nutrients by the color of food. The goal is to get three colors on a plate for maximum nutrition—green, orange and brown are a common successful American pallet. I clipped articles from the newspaper for Journalism, circled the lede or the headline, wrote a headline of my own, then mailed back my work. Somewhere in the world a printer generated a diploma with my name on it that never actually reached me. I like to think it generated a prom dress too, and maybe a date, a scrapbook, a memory.

Mail order classes made for a weird, jumbled soft launch from the stressful mess of high school. I was out a year ahead of the game, trying to get started in college. I was treading water.

In that stretch of time after high school, in the middle of so many other things, my aunt found me this short-term work in a small town, family-owned pharmacy in Forest Grove, Oregon, maybe thirty minutes outside of Portland by city bus. I was grateful. My hair ran down my back like a dark sheet of rain. My life spread out in front of me. An Oregon winter sun fell on the parking lot. The pharmacy had a plate-glass storefront behind where I stood. That window let the sun heat the back of my twiggy legs while I rang up sales.

I bought discount lipsticks like they were my prescription. I wore an apron and shook a set of keys, one for the register, one for the cologne cabinet, one for the person who came before me and somehow never came back. I helped customers in the easiest ways: pointing out dental care, hemorrhoid creams, douches and antibacterial ointments. I’d make guys blush when they came for condoms. All I’d say was, “Did you find everything you need?”

Everybody who comes to a pharmacy needs something. They’re all looking, scanning, hopeful. To ask if they found what they came for? That was my job.

The pharmacist worked in the back half, alongside my aunt. My chores were in the front. They managed prescription meds. I organized mascara, lipsticks and greeting cards. In the middle of the store was a makeup brand called Physician’s Formula—halfway between cosmetics and meds, marking the spot where internal organs bumped against the external organ: skin. It was surrounded by the easy promises of hair conditioners and dye, skin creams, nylons, corn removal tinctures, bunion pads. Beauty.

A pharmacy is a serious emergency survival package, right down to its LifeSavers and Ensure protein drinks, saving your life and Ensuring your future, but it’s always red carpet-ready too. It’s the most well equipped place on Earth.

So beautiful and safe!

A woman came to pick up her prescription. She pulled up in front, parked and put on the brake. Like everybody, she needed a few things. Mostly, she needed meds.

The pharmacist was in the back, bent over a box, holding a box cutter.

Maybe the woman had waited too long to get her prescription refilled. She passed out or had a seizure in her car. She pressed her foot on the gas. She made herself into that unstoppable force meeting an immovable object, or close enough to it. Iron and steel met glass, concrete and rebar. She plowed her big American car through the plate glass window, under that pale Oregon sun, ripping out my counter, driving over my register, leaving black tire tracks on the splay of sky blue and medically-white greeting card envelopes, her car pushed all the way to Physician’s Formula rack.

Those boxes I’d dusted tenderly, methodically, and individually faced outward? Forget it.

This is a story I can tell because I wasn’t there to see the key action happen. If I’d gone in to work, to earn the price of a discounted lipstick once an hour, I would’ve had an Oldsmobile land on my teenage bones, my high school mail order diploma brain, that life of mine spread out underneath her wheels. I would’ve looked pretty, glossy and lipsticked, but dead. There’s no medication, antibiotic, vitamin, scale or splint that can save you from that level of unexpected disaster. There’s no self-defense class, or even a semi-automatic to ward off a thing like that.

A pharmacy is a mess of stop-gap measures and the luxury of human hope. All that safety? I’m for it, but nobody’s fooled. All is vanity. It says as much in the King James Bible, and damn if that isn’t the truth. Not just cosmetics, but our very bodies, our breath, our science and sense of self-importance, it’s all fleeting, rooted in hope.

The woman who drove her car through the building was encased in tons of steel. She was safe, and she was sick. Her body turned on her. It happens all the time.

I didn’t go back to work after she drove through the window and over the counter. The pharmacy had big repairs to tackle. I went to college. In my mind’s eye, when that woman broke a hole in the front wall, it was like I flew out, free and larking. I was set loose from a lovely storefront and carried away with me, like a nesting twig, the pressing question: What to make of a short, mysterious gift of life?

Three dollars an hour.

That’s selling a miracle at the price of pound of cheap, fatty and raw hamburger. Everybody does it in a system we’ve agreed to impose on each other, collectively.

When you’re a kid, adults all asks the same thing: “What do you want to be when you grow up?” I never had an answer. Try out a slow and dreamy, “Um, be?” and they, the adults in question, might take a deep breath then clarify, “To earn a living.”

I was a dirty and barefoot kid, crunching my way through a spotted apple fresh off the tree, when I first turned those words over, thinking about what it meant, to earning this deal of living? I liked it all. I liked fields and animals and hot blackberries. I loved hummingbirds, artichokes, and microscopic lives in a drop of swamp water. I liked the smell of school hallways and winter coats. I could love a snowdrift, right up to the edge of frostbite.

A person is pure potential. There’s the potential for anaphylactic shock, hemorrhoids, snot, scabs, cancer and death, but also ideas, beauty, art, action, and most of all, love.

It’s a complicated history of chance that brings together generations of DNA. It’s a complicated history of luck every single minute that keeps us here. Two forms of gametes, male and female, slam together with a force that changes everything, in a gesture that’s love and violence in varying proportions. That car slammed into the pharmacy, broke through the protective membranes to fertilize the moment with a force that sent me spinning. At seventeen I was still only a walking zygote, a raw, newly formed and rangy, teenage blastocyst. I was free as an unimplanted embryo, a proembryo, that living tissue that has yet to know anything about itself.

What would I do with my own wild and precious life? It’d be years before I’d read the Mary Oliver Poem I’m paraphrasing with that line, but I felt the question deep in my body, in my own skin, muscles, blood and bones. When I reached it, the day I came to read the poem, “The Summer Day,” I already knew the question well. It took me longer to find an answer. Sometimes the answer still slides out of my grasp.

From where I stood, that dose of car crash was a cure, an intravenous shot of gratitude. Nobody was killed. My real job was bigger than the pharmacy, of course. My assignment, given to my brain, body and spirit, by the universe, was to figure out how to live. The optimism is in going forward without security, just hopeful, fragile and human.

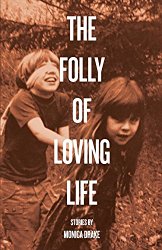

Monica Drake’s stories and essays have appeared in the New York Times, Paris Review, The Sun, Beloit Fiction Review, Oregon Humanities Magazine, Northwest Review, and Nerve.com. Her most recent book, The Folly of Loving Life, is finding wonderful reviews. Her earlier novels include The Stud Book and Clown Girl, which was optioned for film by Kristen Wiig. She can be found on Amazon here and on Facebook here.