By Lesley Harper

When I was a kid, I had panic attacks. I worried when my dad went into the bathroom late at night that he may not come out and that we would find him swinging in there once one of us was brave enough to open the door. I would close my eyes and hold my breath waiting for the sound of the toilet flushing and the footsteps back to his bed. My mind would play tricks and my heart would sometimes skip one of its beats when I felt there was about to be a gunshot or the sound of him stepping off the side of the tub and into his death. I didn’t have the word depression then or any of the qualifiers so often accompanying the word: clinical, chronic, cyclical, situational. But I had a profound understanding that my father was deeply sad and I lived in constant fear of the damage his sadness created in our home.

My dad and I had much stacked against us from the beginning. He didn’t respect girls or women, although he didn’t distinguish between the two. He referred to his 85-year old grandmother as a “good girl” and all girls from birth to death had domestic responsibilities and were required to obey men and anything outside of that was misbehaving and punishable by whatever the whims of the man dictated. I came out of the womb disappointing him. My sister was born in 1968 and by the time I was born in 1972, my dad had had 4 years to think about how soon, his son would be on his way. My vagina was a serious bummer. I don’t remember a time when my dad and I were not butting heads. For some people, self-preservation in a situation where one has no power means keeping quiet and backing down when it looks like one may be pummeled. I wasn’t born with that. I knew that I would be beaten up no matter what I did and so for me, self-preservation was never backing down because my spirit and respect were the things he wanted the most and he never got either.

At 6’4” my dad was a formidable man. He regularly became enraged and would rip the leather belt out of his pants. I can still hear that whooshing, slapping sound sometimes at night. His face would get red and he would walk toward me with murderous eyes in a contorted head, using both hands to snap his belt as he approached. He would then either put me over his lap with my pants pulled down and whip me on my bare ass or he would chase me through the house lashing me all over my body until he was done or until my mom was able to stop him. I would go to bed many nights with purple stripes of goose-bumped flesh and I would arrange the blankets in such a way that they wouldn’t touch my wounds. I would sometimes set up a fan to blow on to my body offering some relief from the constant burning. In those moments I would think, “Why this? What did I do?” And I would grieve deeply for the thing I wanted so badly and knew I would never have: a father who loved me. It was so important to me and for my method of self-preservation (you don’t win. you didn’t get me. you can’t have me. you’ll never win.) that he not see me cry. Most of the time, starting in grade school, I would wait until I was alone to cry and these were the times at night when I would hear him go into the bathroom and although I regularly fantasized about him going away forever, the thought of him killing himself in the bathroom terrified me and I prayed to the god he made me pray to that he would come out alive. I would often write letters to friends that would never be delivered all about the great things I was doing with my dad. This imagined dad would read stories with me and tell me about his own childhood. He would take us on vacations and build me a bicycle. He would let me watch baseball, he would never call me a whore, he would never hit me and he would laugh at all my jokes.

As I got older, into my teens, I realized that if I stayed at home I could be killed. So at 14 years old, I ran away with my life-long best friend who didn’t have the best home situation either. We ended up in NW Portland with a group of marginalized youth and we created a chosen dysfunctional family where I was wildly unsafe for different reasons but relished my freedom. I experienced foster homes, psychiatric wards for adolescents and substance abuse and by the time I was in my 20’s, I was more or less living a typical life for a 20-something weirdo in Portland. I went through my 20’s and most of my thirties so incredibly angry about the things that my dad had done to me. I felt alienated from the rest of my family because they often encouraged me to let my anger and hurt feelings go and to stop rocking the boat and making everyone so uncomfortable by bringing up the past. I never wanted to go to family birthday parties because although my parents divorced when I was 19, he was still included in all of the family gatherings and seeing him made me physically ill. If I didn’t come, my family would get mad at me and say I was letting them down. If I did come, I would drink too much, vomit and be destroyed for days after by the horrible compromises I had made to avoid rocking the boat. He would try and hug me and I would try to duck out, no longer backing down because I didn’t want everyone angry with me for causing problems. I was so tired of being the cause of problems. During these times, I experienced a new way of grieving which was to still cry and long for a dad who loved me but also for a family who supported me.

In my mid-30’s things started to change. My siblings and my mom and step-dad all started to see things in much the way I always had. Most of them apologized to me for the time it took to get there and they stopped expecting me to show up if he was there, eventually they stopped inviting him. I went through intense trauma recovery and EMDR therapy for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and approaching 40, I found that I was occasionally experiencing something new. Happiness.

I had my daughter when I was 36 and something happened around my grief and my dad. I started to see his humanity. I thought about how we all made fun of him when he would say he had to get up at 5 in the morning. We would mock him. I thought about what that really meant, though. To get up at 5am every day and to go to work on cars even though he had rheumatoid arthritis from quite an early age and lived in constant physical and emotional pain. I thought of how he wasn’t friends with any of us in his family, how he didn’t spend time with anyone who wanted to spend time with him, how he struggled with his depression and the memories of the abuse he suffered as a child which was part of this family legacy and how much more I understood about him now that I was an adult with a child and living with chronic depression.

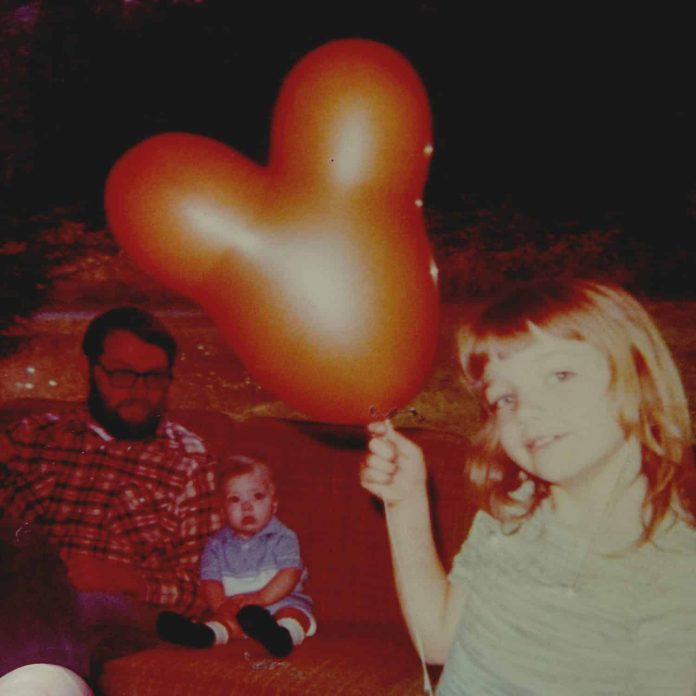

A couple of years ago my mom’s brother sent us a DVD of transferred super 8 films which captured years of family moments. I sat with my Nana, my mom, my step-dad, my partner and my daughter and watched the 1970’s. I watched myself playing and fighting with my sister. I watched my Papa drinking, dancing and teasing us all, I watched my mom making jokes and being so animated and chasing us around, I watched my Nana fret over my Papa with a worried smile on her face, and I watched my dad sitting back in almost all of these looking withdrawn and alone and terribly out of place. Then something surprising happened. It was a film of all of all of us up near Mt. Hood. It was a shot of a meadow and blueberry bushes and the mountain in the distance and suddenly my father and I walked into the shot. I was about 5 years old. We were holding hands. He was smiling. I was smiling. I looked up at him and said something and laughed and ran off, swirling around him with the enormously energetic body I have always fought to control. He kept smiling as he watched me run off to join my sister in this meadow and the scene changed abruptly to a picnic in Tennessee with my uncle and extended family. This moment with my father took my breath away. I have no such memories of smiling with him, enjoying him or of him enjoying me. I started crying the most quiet, cathartic tears in that moment and my mom and my partner seemed to understand exactly where my tears were coming from. My grief for my young self and for my mentally ill father were enormous in that moment and I was grateful to have connection with that, no matter how painful.

My dad lives alone surrounded by mold and mountains of car parts in the house where I grew up. I will never have a relationship with him, but I have forgiven him and feel empathy for him now. I no longer yearn for a father who loves me but I still grieve so much loss around my youth. I get on stages and share what I have learned or not learned with audiences in hopes that we will all gain something from this transparency. I’m no longer afraid of this grief because I put it into my stories and my work and I have greater empathy in the world as a result of honoring the grief I feel now and have always felt. I never experienced peace as a girl and I rarely experienced peace as a young woman but in finding the humanity in my father and in finding a connective thread in our emotional lives, I experience peace now. What’s more, I live comfortably with the discomfort of my grief.

This is perhaps the saddest story I’ve ever read. You write beautifully, and I am so glad you were able to overcome that sad part of your life. The blessing of your being able to forgive him is an inspiration.

I’m glad you made it!! xx’s

Lesley – I lived in these words in so many ways, too. You express it so beautifully and so wholly, all I can do is nod and be in awe. Thank you. I’m so sorry. But thank you.