By Haili Jones Graff

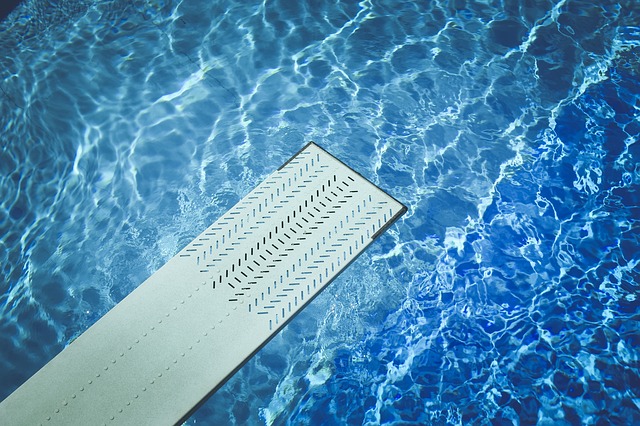

I stand at the edge of the pool, my feet swollen and pale against the water-darkened concrete. Inching unpainted toenails closer to the lip, I line my insteps parallel, then flex, arches arched, seeking strength and propulsion in my stance. At thirty-eight weeks pregnant, I am nearing one hundred ninety pounds, at least twenty of which jut from my midsection in an arc that I’d expected to be smooth, spherical, beachball-like, but which is often distorted by the shape of the small human pushing out—even as he has occupied all regions of my interior space, so now his skull, knees, feet, fists send their impressions outward, strain against, almost through and past my taut, stretched skin, a skin that appears drum-thin sometimes, barely able to contain the force within it.

Sounds bounce off the walls of this damp, echoing room and commingle, filling my head—the plish-plashing of swimmers in other lanes, wet feet slapping cement, the murmuring of two lifeguards kitty-corner from me across the pool, all strangers with trim bodies, goggle-clad with short hair or hair slicked back. I am goggle-less, thirty-two years old, at nine months pregnant the very antithesis of thin, my dry hair almost to the middle of my back in disarray. I am interested in them, these other swimmers, only insofar as they are interested in me. Are they curious? Watching me with awe, or maybe pity? I project onto them my own cacophony of feeling, but it doesn’t matter. I have only one purpose here.

I take a deep breath and release it—not enough. A deeper breath and hold. The water ripples, laps softly. I spike my hands together above my head, an arrow, or if I were a different woman—a prayer. Bending my knees, I arch onto the balls of my feet, bounce once, spring… and leap. Flip, I say to the breech child inside me. Flip, I mouth, flip, I demand, flip, I command, flip, I beseech. Flip!

The water receives me. And for a moment, I am weightless in its embrace.

***

It was just a few weeks ago that my three-woman team of midwives had mentioned at a routine visit that my baby was breech. They didn’t seem overly concerned and neither was I—just something to be aware of, keep an eye on. It was early yet, and I still had lots of room in my uterus for the baby to move into his final position: he should settle head-down by thirty-two weeks, full term at thirty-seven. Really, they assured me, he could flip right up until the moment of birth. But in the meantime, there were things I could try if I wanted to encourage him to settle vertex, to move his head from its resting place between my ribs and trade it for a nice, comfy spot in my pelvis, ready for exit from this portal.

One of the midwives recommended a website called Spinning Babies, where I read that I could lean, say, an ironing board up against the couch and lie on it with my head toward the floor—the breech tilt—or have my husband shine a baby-attracting light low on my abdomen and play melodic, enticing music to my pelvis. The baby might be encouraged to move closer to the external stimuli, squirm his head down to examine this strange brightness or better hear this new noise. I could press a bag of frozen peas to the top of my ribcage, where I felt, always, his skull rounded against my ribs; maybe he would shy away from the cold. An acupuncturist could burn smoke near my pinky toes: the moxibustion technique was a proven winner, a crowd favorite. My mother suggested that I dive. It worked for one of my sisters—when her baby was breech at thirty-something weeks, my pregnant sister dove into the icy waters of Montana’s Flathead Lake, and whaddayaknow, a few days later, the baby flipped.

I have to admit, I scoffed a little, I did. Lights and music? Okay, that one I might try; at the least it might provide some silly, tender moments with daddy-to-be. Surely our child would come hither for Slayer. But magic baby-turning smoke? A pregnant woman, a pregnant me, upside down on an ironing board? Just contemplating the mechanics made my back ache. The same went for diving. Yeah, great for my sister, Ma, but me?

***

Perhaps it’s obvious, from my earlier mention of midwives, that I’d planned a “natural” birth. Early in my pregnancy, I’d decided on a birth center less than twenty blocks from my northeast Portland, Oregon, apartment. A home birth would have been ideal, but I didn’t have a home I felt comfortable birthing in. My husband and I lived in a one-bedroom walk-up on the second story of an old bricker, with four cats and sixty-something years of accumulated media between us. I had no desire to de-cat and could not imagine how to de-clutter this apartment. And I was afraid to wake the neighbors with the racket (we’d already had a door-note about wearing shoes in our apartment).

The birthing center was in a remodeled Victorian. Hardwood floors, creaky stairs, communal kitchens both upstairs and down. Most important: beautifully appointed birthing rooms. Light, airy, sun-soaked rooms with large, inviting, quilt- and pillow-topped beds and mermaid-tiled birthing tubs, some rooms even with fireplaces.

I wanted a drug-free, incision-free, Pitocin-free, heart-monitor-free, hospital-free birth. I wanted the baby to come on his own time. I wanted to labor in any position that felt right, to give birth in the water if that also felt right. I wanted to rediscover breath, to find it within me to grunt or howl or murmur mantras or recede, to conquer the pain and the fear within me, to learn my true limits, to confront my body’s darknesses with strength.

I wanted to welcome my child from my body with my body, to pull him naked to my breast and hold him there until his umbilical cord quit pulsing, to release him to the world by holding him to me. I wanted him to feel like he was home, born into the circle of family, in a safe place, a place devoid of half-faced strangers in scrubs, far removed from the gleam of stainless steel instruments, the alien glow of harsh fluorescent lights. Did I, the uninitiated, romanticize the hell out of birth? You bet I did. But I wanted all this and more for my child, for my husband, and for me. Most of all, for me.

***

In my teens and early twenties, I’d been hard on my body, and in return my body had hardened on me. When I was a young woman making my way from Montana to Denver and back again, then from Montana to Seattle and back again, my body was just the ride I took to get where I was going. In many ways, I was a self divided, inflicting upon rather than centered within my body, enacting the whims of a most voracious id.

I drank, I smoked, I drugged, I fucked and I fucked hard, drugged hard, smoked hard, drank hard. By my twenty-first birthday, I’d passed through two in-patient treatment centers and one mental ward. I’d hit all the high notes: had an abortion, been raped. I blacked out regularly and on purpose. I’d been in several car accidents, fallen down I don’t know how many times, and even, on occasion, been beaten, pushed, kicked—and done beating, pushing, kicking of my own.

And how did I sustain myself? Maintain myself? Perhaps typically, in the first years out on my own after high school, I lived on pizza, Top Ramen, tortillas smeared with butter, bar food, the occasional care-packet from my mom. I didn’t exercise. I bruised easily. Sometimes I got so sad that I bit my hand, so angry that I beat my thighs with my fists, so lost that I sat, rocking, on my knees, or, unable to cope with the intensity of my emotions, cut myself with razors until I felt like I could breathe again. I often wanted to leave my body, to flee it, to end my inhabitance. By the time I returned home at age twenty from my second failed, meth-fueled attempt at urban existence, I had almost managed the escape—weighing one hundred and three pounds at five-foot-seven, my body was fleeing me.

I met my husband—bass-strummer, photo-taker, soccer-player, Lily-of-the-Valley-picker, this exquisitely gentle, exceptionally creative man—in my mid-twenties. Gradually, from the safety of a relationship that would grow into a marriage, I began to give my body a break. I drank less, drugged less, smoked less. I became interested in food, got the occasional massage, began to imagine caring for myself as I now was cared for by another. I also added thirty or forty pounds to the hundred and thirty I had reacquired by then, no longer waiflike basking in any and all male attention that glanced my way; no longer cheekbones, hipbones, elbows, ribs. Right before I turned thirty, three years into my marriage—my new me!—I discovered I had severe degenerative joint disease in my left hip—the arthritis of a seventy-year-old woman. Doctor after doctor asked me if I’d ever had an injury, if I’d been in a car wreck, if I’d played sports—why this advanced degree of damage in such a young body? And I would think, Pick a car wreck, any car wreck. Pick a fall, any fall. Is meth bad for your bones? Then I would raise one eyebrow and pull the chummy routine with whomever was filling the lab coat that day, saying, “I grew up in Montana, so I’ve been in my share of car wrecks.” And, “I was pretty hard-living there for a while.”

So my body and me, we had some distance to overcome, a rift long grown between us. And pregnancy, to me, was a beautiful thing, a healing. During those nine months, when another body called mine home, my body finally felt like home to me, too, rather than a place I simply visited when I needed something for myself or someone else. I felt the life growing within me as a wondrous gift, the extra weight transformed: life-giving, rounding out the hardness, my body a shield instead of a fist.

I wanted to believe that pregnancy heralded a change in me, a move toward an embrace, however nascent, of the full power of my femininity—creative, generative, manifesting, selfless—lightness to round out the dark. I anticipated that the birth would complete a long-sought, tough-fought, longed-for transformation, and envisioned a rite of passage, a ritual of belonging: in my body, in a family of my own creation, and maybe even in the mysterious world of women at home with their womanliness.

***

One spring-bright Portland morning, five or six months into my pregnancy, as a friend and I were walking to a restaurant for brunch, he expressed skepticism about the idyllic birth-center birth I had just rhapsodically described. My hackles went up; I bristled, protested vehemently: The medicalization of birth is society’s imposition, another way of stripping women from their power, their wisdom, the rightness of their experience. Women are supposed to give birth, have been doing it for thousands of years. C-section rates blah de blah, episiotomies blah de blah, maternity leave blah de blah, patriarchal society blah de blah: the culture of birth in America sucks.

At that point in my pregnancy, I nourished myself on a steady diet of books with titles like Gentle Birth Choices (choose natural!), Birth Without Violence (natural!), and Women’s Bodies, Women’s Wisdom (natural! wear your baby! breastfeed!), most from my mother (one birth-center birth, one home birth, all five “natural”) by way of one of my younger sisters (one emergency C-section, one home-birth Vaginal Birth After Cesarean). Dr. Sears, a strong advocate of natural birth and attachment parenting methods, was my go-to guy, his Baby Book never far from my bedside. I was going to not only give birth naturally, but breastfeed, co-sleep, wear my baby—nurture the living daylights out of that kid.

Still, my friend maintained his skepticism. I ended my protestations, serene: I don’t care what you say, buddy. A birth is not a medical event.

***

At thirty-five weeks, with our child still breech in my belly, my husband, Shane, and I drove to the office of the doctor my midwives had recommended, a naturopathic physician with a reputedly high success rate in performing manual external version—hands-on-belly baby rotating. A version is typically performed in a hospital at thirty-seven weeks, when the baby is full term and can survive in the event of spontaneous delivery or emergency C-section, both potential outcomes of the procedure. But the midwives wanted me to try earlier, while there was still room in my belly for the baby to move. Our efforts to encourage the baby to turn on his own had failed. A hundred times a day now I lay hands upon my almost bursting flesh and pushed until I felt my child’s head still resting near my heart, the contours of his body jack-knife bent. A hundred times a day I whispered, flip.

We had but weeks left. So here Shane and I were: taking aggressive action.

The disorder in the doctor’s office surprised me. There were stacks of books, manuals, and papers leaning high on a counter under none-too-clean cabinets that I could only assume contained medical supplies. The bulletin boards lining the walls teemed with cards, scraps of paper, family photos. The lighting was dimmer than it seemed like it should be. I didn’t know whether to be comforted or disturbed by this homey approach.

The doctor struck me as kindly, wizened—whitening hair, bright eyes, a lined face. While we talked about the procedure, he gave me a pill, something to relax my uterus. Shane and I shot each other a dubious look—are we really going through with this?—but I hoisted myself onto the table, my husband’s hand warm on my shoulder, exerting the faintest of pressures. I leaned back against the loud-crinkling paper sheet and hiked up my shirt, rolled down the wide elastic waistband of my pregnancy pants. The doctor slid his hand across my abdomen in a perfunctory caress, spreading warm jelly for the ultrasound that would help us determine if there was anything structural impeding the baby’s movement. Then, pushing into my belly with the ultrasound wand, the doctor mentioned that the umbilical cord was lying across the baby’s neck. What did that mean? I wondered, tensing at the words “umbilical cord” joined in a sentence with the word “neck.” Shane’s hand squeezed tighter. When I asked for clarification, the doctor seemed unconcerned—the cord was not wrapped around the neck, just lying over. I strained to make sense of the patterns of light and darkness that flitted across the screen near my feet. I would worry for the next hour: what if?

It was time to perform the version. The doctor reached across my body to hand the heart-rate monitor, called a Doppler, to Shane. He gave a brief tutorial on how to use the plastic wand, how to follow the baby’s heart, how to respond if the tempo sped or slowed, transmitting signs of fetal distress. Shane took the Doppler, trying with a firm smile to project a confidence he would later tell me he did not feel. He leaned toward me, his heavy-metal hair half-hiding his face as he held the Doppler to my exposed, mountainous belly. And we began.

Shane and I were both unprepared for the physicality of the procedure. For how the doctor laid his hands on my bare stomach and reached almost into me, through my skin, to grip the baby’s body, to push, prod, twist, turn, and hold him, force him, make him budge—my son. We were unprepared for how we’d chase the baby’s heart, our own hearts wild and leaping at each dropped beat or loss of contact. Unprepared for how I breathed, hummed, moaned, hissed, my voice almost unrecognizable, a sound that has been and will be since the beginning of time—primal, animalian—even as a more interior voice sought for my baby, murmuring beneath language, aiming to soothe, to release, reassure. And the doctor’s voice rasped, “Come on.”

Another lifetime later—or was it only one hour? two?—my husband and I stepped from that sweltering, smothering office and into the lobby, out from the lobby and into the parking lot, blinking like newborns in the late afternoon light. The tears began. I could not stop them, and did not try.

I leaned my back against our car for a moment, absorbing the metal’s heat.

“It’s like we’re forcing him… it doesn’t feel right, to make him…”

Shane and I looked into each other’s eyes and saw the same thing. Defeat? Acceptance? How to distinguish one from the other?

“I’m done,” I said. “Done.” I labored into my seat and strapped myself in.

***

But was I really: done? At thirty-seven weeks, I transitioned from midwife care to an obstetrician. Faced with an almost certain cesarean, I turned to my go-to sources—Dr. Sears and company—for advice on how to cope, on how to make my now undeniably medical birth the best possible birth.

And found almost nothing. Dr. Sears essentially avoids the topic of C-section altogether. The only part of his otherwise exceedingly thorough, 767-page Baby Book relating explicitly to C-section, about breastfeeding after a C-section, ends with the advice: “Be patient. It takes more time, support, and perseverance to achieve a successful breastfeeding relationship following an operation. Some of the energy that would otherwise go toward breastfeeding is shared with healing your own body.” So, uh, not only was a C-section so undesirable that Dr. Sears didn’t even want to talk about it, but the operation would also affect my ability to bond with my baby in numerous other ways, breastfeeding not least among them. Oh, and I was sapping energy that could/would/should have gone to the baby for my body’s own selfish healing. Grr-eat.

In general, most of the books talked a lot more about how to avoid a C-section than about how to make the most of an inevitable one. But one book really got to me.

In Women’s Bodies, Women’s Wisdom, after giving a pass to women whose uterine structure prevents the baby from turning (not me!?), Christiane Northrup, M.D., goes on to state:

It’s clear that in some cases the baby is breech because of the tension that the mother holds in the lower half of her body…. anxious and fearful women have a higher incidence of breech presentation… attributable to the fact that fear, anxiety, and stress can activate sympathetic mechanisms that result in tightening of the lower uterine segment. My obstetrician colleague… feels that a baby may be in the breech position because it is trying to get closer to its mother’s heartbeat—to feel more connected to her.

The baby was trying to comfort me, huh? So if I could just master the art of equanimity, my baby could stop mothering his mother, untether from my too-rapidly-fluctuating heartbeat and float serenely down to his proper birthing position in my peaceful, well-adjusted, earth-mother womb.

Reading this in the emotionally porous late stages of pregnancy infuriated, frustrated, and, most of all, saddened me. In my less well-modulated, more narcissistic moments, I felt I had nobody to blame for this breech baby but myself. I was a failure as a woman, as a mother, as a spiritual being.

A phrase from the book leaped out at me, lodged in my consciousness: “Women labor as they live.” Northrup elaborates:

Having participated in hundreds of cesarean section deliveries and other forms of medicalized birth over the years, I’ve learned that our current dilemmas over birthing start long before a woman ends up on the labor and delivery floor. It starts years before she even gets pregnant! Each of us carries the seeds within ourselves, and we must look at the ways in which we daily participate in less-than-optimal treatment.

Women labor as they live. And so it was to be a C-section for me. Numb from the chest down. Detached from my body and unable to interpret its sensations. Operated upon, rather than operating. Robbed of agency. A vessel emptied. A body scarred. Was this how I had lived?

I was angry at Christiane Northrup, M.D., because I feared that she was right: the baby was stuck, because still, somehow, I was. The birth was not an empowerment, but rather a mirror: a reflection of that early me. I had not escaped her at all—she was the only woman I knew how to be, my transformation forever incomplete.

***

Can I tell you a secret? Part of me, baby still breech at thirty-two, thirty-four, thirty-eight

weeks, me head-down on a wobbly board borrowed from a shelf, toes curling over the lip of that pool—even for all my seemingly determined activity, some part of me was just going through the motions. Doing what I was expected to do. Following every possible piece of advice.

I was trying to shed the blame for my body’s failure. Well, shrug, I did everything I could do. Now when my mom asked me if I’d gone diving—it worked for your sister—I could say yes. When the O.B. asked if I’d tried external cephalic version? Yes. Maybe too early in the game to be effective, and with a guy my husband and I now referred to as the “witch doctor,” but yes. And when the midwives asked if I’d tried cold at the top of my uterus, heat and music and encouraging speeches from dad-to-be at the bottom of my uterus, the breech tilt, the Webster chiropractic technique? Yes, of course yes. Moxibustion?

Damn. The magic, baby-turning, pinkie-toe smoke! I’d canceled my moxibustion appointment in favor of a last-minute slot for the failed external version with the witch doctor, and failed to reschedule. Did I somehow miss the one thing that might have worked? The breech baby, the C-section: still on me.

***

My mom has always told me I was a “water baby.” Immediately after being born in a Georgia birthing center, thirty-three years ago now, I was slipped into a warm tub of water, a Leboyer-method birth, a birth without violence. I am told that I floated there in the water, tearless, fearless, wide-eyed, and smiling.

On the verge of becoming a mother myself, I’d found my way to the water once more. Thirty-eight weeks pregnant, four weeks after I’d said, “I’m done,” and, for a moment, believed it. Diving, and diving, and diving again. Beseeching the water. Embracing it.

My son, too, had been diving. I imagined him trying to do a pike, an advanced dive—bold, ambitious. When he reached down to touch his toes, all was well, he made it! But then he found he couldn’t unfold: it wasn’t up to him. There were structures in place, histories and mysteries, two bodies growing both into and away from one another, two beings who were more than their bodies becoming both two and one. My body would have to release him. Would I be able to release my body?

I dove for over an hour that day at the university pool. I dove, and once in the water, I stood on my hands, did somersaults, rolled and spun. The water held me safely, as my own waters held my son.

I try now to imagine the strength, the beauty, the determination of that pregnant body and the woman who lived in it, to see that luminous profile cut stark against the blue of the pool before leaping and merging, come what may.

;