By Leigh Hopkins

When I was a literacy center director in Philadelphia, I worked with thirty after school programs run by neighbors who were doing their best to give kids what schools couldn’t get to. Programs held in abandoned dollar stores and storefront churches, or in homeless shelters run by activist nuns. Bodega reading circles. White-haired volunteers reading to kids in synagogues and mosques.

My nonprofit shared the program’s early successes with big foundations like Ford and Pew, and because our centers often worked in partnership with “faith-based organizations,” the Bush White House wanted to know about it.

Churches they understood.

White House staff visited our programs and invited us to Washington. When it came time for the final interview that we hoped would lead to funding, I spouted literacy and poverty statistics while stressing the need for the separation of church and state. I emphasized the importance of program quality, replicability and scale. After two hours of questioning, they began to wrap things up.

“One last question,” said the man from the White House. “Is there anything about you that could be potentially embarrassing to the President?”

I squinched my eyebrows. Refocused my attention on the American flag waving at me from his lapel. “Other than being a lesbian Democrat running a faith-based initiative for the Bush White House, I can’t think of anything.”

He blushed and looked at his clipboard. Gathered his papers and stood. “OK, I think that’s it,” he said. “We’ll get back to you.”

A month later, we got the grant.

*

Soon, the program’s success captured the interest of foundations and researchers across the country. We expanded to 500 literacy programs in seventeen cities, coast to coast. I wrote Op Eds and gave speeches, and I was invited to the White House for lunch, where I ate Cobb salad and molten chocolate cake. I nodded and smiled and swallowed the oily knowing that for the kids in our programs, an after school snack was also dinner.

When the White House asked us to prepare a “signature site” for a visit from the U.S. Secretary of Education, I knew exactly where to go. Reverend Missions was a Pentecostal minister in her seventies and the beating heart of her community, but when I walked in the door to her program the day of the visit, the classroom was a wreck. Noisy and swarming with kids. Reverend Missions had gotten her hair done for the event, and she sat in a big armchair wearing a plum wool skirt suit and bedroom slippers so her ankles didn’t swell. By then, we were old friends, so I got to the point.

“Reverend Missions, what happened?”

She just laughed and clucked her teeth.

I looked at my colleague. We took off our suit jackets, grabbed a bottle of Windex and began wiping down tables. Soon, a catering truck arrived with five enormous platters spilling with finger sandwiches. When the sign “WELCOME, SECRETARY PAIGE” was hung, we took the kids through a dry run. Then we settled down to wait.

Two hours.

Tuna and egg salad sandwiches sitting in the heat.

Finally, I got the call. The Secretary’s schedule was too busy. He wasn’t coming.

When I told Reverend Missions the news, she sat quietly, looking at her laced-up Sunday shoes. She ran her fingers over the nubby fabric of her plum suit, very slowly, back and forth. Then she rose from her chair, picked up a platter of finger sandwiches, and dumped it in the trash.

“Reverend Sermons, I’m so sorry,” I said. “Maybe we can give the sandwiches –”

She picked up the second platter and hauled it into the big rubber bin. “Ain’t nobody gonna eat your fancy sandwiches.”

I opened my mouth to apologize again, but Reverend Missions just put her hand on my shoulder and said: “Baby, it don’t matter. We still gonna do what we gonna do.”

*

When I moved to Brazil in 2010, I was riding high on the wave of hope brought by a new kind of government. I felt certain that our hardest work was behind us, and twenty years of coastal book-running had left me ragged. My Brazilian wife came to the U.S. on a student visa after being trampled by mounted police, so she looked to America as a land of free expression and opportunity. After 20 years away from her country, she was homesick. We sold our house in Philadelphia, and then we did something crazy – we bought a farm in the mountains above Rio. We started a vegan retreat center and lived off the land. Bee swarms and venomous snakes. When cancer took her three years later, I understood that all along, we were bringing her home.

I returned to the US with two suitcases and a shadow-self. My wife was gone. Our farm was looted and stolen. Every last penny spent on cancer. As I dragged my only remaining belongings through baggage screening in Houston, I felt like an estrangeira – the Portuguese word for foreigner, meaning “stranger.” I looked around at the tired faces, people from far-flung places seeking refuge and new beginnings, and for the first time, I thought I had an understanding of what this country represents. Of the will to remain hopeful. What it means persist.

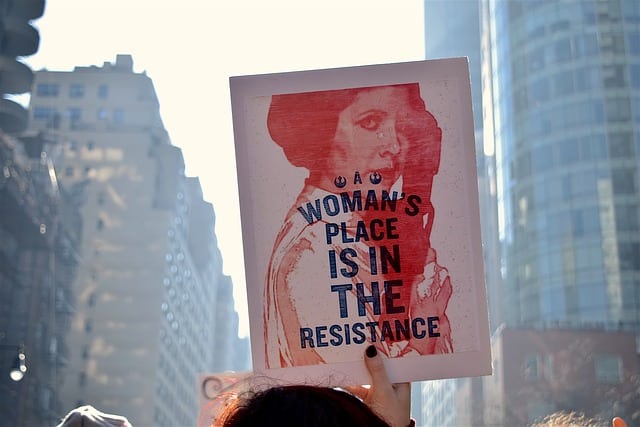

And now? How do we make a home in this country when any one of us is told she doesn’t matter, that she doesn’t belong? How do we persist?

Throughout my life, I have been surrounded by strong women. I will be forever grateful to have worked in Washington at a time when my voice was heard by a Senator from New York whose office took my calls and answered every email, whose staff always found thirty minutes to sit down with me in person, no matter how busy. (I’m still with her.) I am stronger because of women like Reverend Missions, whose program still serves the families of North Philadelphia, or my dear friend Morgana, who created her own family through the foster care system.

When I am in need of inspiration, I look to my new wife’s daily painting practice, or the writing of my friend Joy Harjo. Her book of poetry, Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings, reads like a guidepost for these times. I stand behind women like Senator Kamala Harris, who gives voice to the voiceless and vows to stay focused on climate change. I am still hopeful because of Senator Elizabeth Warren, who was silenced on the Senate floor for reading a 30-year-old letter written by Coretta Scott King. Who persisted in reading the letter outside the Senate doors.

We have been doing this since always.

Baby, we still gonna do what we gonna do.

Thank you for this amazing piece. I don’t think i’ve ever read something as layered, yet direct, a picture of everything … just everything. I’m stunned! xx’s

I love Leigh’s writings! She has such a way with words, weaving threads together in in a thoughtful, loving pattern and revealing deeper truths and understandings.