Note from Jen Pastiloff, founder of The Manifest-Station. This is part of our Young Voices Series for Girl Power: You Are Enough. We are always looking for more writing from YOU! Make sure you follow us on instagram at @GirlPowerYouAreEnough and on Facebook here.

By Gabriella Geisinger

I am a thief.

At age fourteen I began shoplifting. It was part of my teenage rebellion. A ring here, a bracelet there; a tube of mascara or lipstick would find their way stealthily into my pockets as I sauntered, impervious, past cash registers. I only acquired items that were small enough to conceal in the palm of my hand. By age eighteen the habit had waned. My first year at college provided whatever psychological freedom I required to keep the mild kleptomania at bay – for the most part.

With adolescent abandon, my freshman year passed uneventfully by. August soon became May and I packed up several suitcases, shoving them into our Pampolna’d bull of a car – a black minivan with a nasty habit of spewing maple syrup scented steam when it over heated – and returned to New York City for my first summer at home in three years.

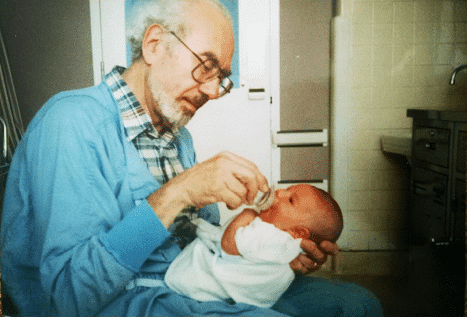

In the summer of 2008 a heavy oppression stifled my duplex apartment. It was the inevitable, suffocating weight of change. We were moving. My brother had fallen in love with a small private (technically Catholic, though no longer associated with the arch diocese of New York) school on Staten Island. The forgotten borough was always on our radar as my entire extended family resided there. My mom was eager to return to her home borough, wanting to be closer to her parents. My dad was the hold out – an 83-year-old New Yorker, poet and Renaissance man, he was not prepared to make his final journey one to a borough infamous only for the dump you can see from outer space. As for me, I told my mom that I couldn’t care less where we moved.

***

I am also a liar.

***

The phone rang around eight in the morning on June eighteenth, a month and a half before our move date.

‘So that was Phyllis… Jonathan forgot his coat.’

‘What do you mean?’ I blew the words into my cup of coffee. My brother was notorious for forgetting, losing, ignoring, and generally not caring about his material possessions – something my mother had bi-monthly aneurysms over. It shows a lack of respect! She insisted. I agreed, though secretly ascribed it to a lack of maturity, not a malevolent undermining of her efforts to procure the perfect Christmas present.

‘Bob can you go get it?’

‘I’m not really feeling all that energetic…’

‘I can go, mom.’ I was eager to get out of the house. With no plan for the summer, anything to do was something to do. My brother was in the Hamptons at his best friend’s house, and was therefore temporarily off the hook. My mom had long ago waved the white flag at the New York City subway system, favoring the cool air conditioning of our battered minivan to sharing a tin can with several homeless people and a mariachi band. We set out for school, as we had done so many mornings before.

‘So how do you think dad is handling the move?’

‘I don’t know…’

‘I know you have an opinion on this, Gabriella…’ my mother, the therapist, always insightful.

‘You act like he’s going to live forever.’

The rest of the trip was passed in silence. I was let out on the side of a narrow street that passed below the FDR drive. On the east river, the United Nations International School floated precariously on a pier. Sandwiched between a gas station and an apartment complex, it was inconspicuous save for the pale blue UN flag that hung limp in the damp summer air. I crossed the street and walked into my nearly empty Alma Mater.

Retrieving my brother’s coat from Phyllis, the staunch middle school attendance officer, consisted of a series of apologies on behalf of the Geisinger family for being such fuck ups. My own reputation in middle school was one of extreme angst and despondency all done with artistic flourish; my brother’s was one of forgetfulness and academic oscillation. With the coat stuffed in a paper bag I trudged home, regretting the decision to be a dutiful daughter.

My apartment was quiet, which was rare. Usually chatter filled the small space and like water would pour out of any open passage as soon as it was permitted. If no talk was to be had then the sound of WBGO, a public jazz radio station, would find its way into every nook and cranny.

‘Dad?’ I dropped the coat on the bench by the door; my eyes flickered to the stain where I, at age 11, tried to remove spilt nail polish with acetone and succeeded, but removed the wood finish off the bench as well.

Horizontal on our brown suede couch, my father’s face was covered by the Wednesday edition of the New York Times. ‘Dad?’

The pages fluttered like butterfly wings. ‘I must’ve fallen asleep.’

‘Yeah,’ I laughed and plopped myself into the chair, setting my feet on our coffee table.

‘You know, I always liked those shoes.’ My dad, being an artist, was keenly attuned to the fashion needs of a teenage girl. ‘I think I’m going to go take a nap.’

‘Okay, have a good nap.’ My gaze briefly met his as I opened my laptop. I fell into the black hole known as the internet, and only re-joined reality as it was nearing 2pm.

I climbed the L shaped stair, and pushed through the second door on the right, kicking off my brown sandals. Bare-foot-falls brought me to my parents’ room. Their bed was empty.

‘Dad?’

***

Most people recount moments of trauma with exceptional detail. My memory doesn’t quite serve so well. It becomes a blur, a series of screams and frantic, trembling searches for the cordless phone that no one ever remembered to put in its right place.

‘911 what’s your emergency?’

Words fell like dominoes.

Dad.

Dead.

No I can’t lift his body.

Apartment 726.

I tried that.

Yes, I’m CPR trained.

You want me to what?

I tried.

He’s definitely dead.

***

I made my retreat to our kitchen, picking the most far away place to make my next flurry of phone calls. My kitchen floor, covered in peel-and-stick linoleum tiles feigning terra cotta warmth, was cold against my legs. I awaited the inevitable arrival of my family while a dozen EMT and firemen in heavy boots thundered past, whispering to each other. My family trickled in; first my grandparents, then my mom’s best friend, and then my mom. As a therapist, she was hard to reach. It took me seven tries to get her, and then she spent hours contacting her clients to cancel appointments before she could come home. By then the EMTs had blocked off the second story of our apartment, forbidding anyone to go upstairs.

***

‘I want to see him.’

‘No you don’t, ma’am.’

‘Yes I do.’

‘Mom – trust me. You don’t.’

***

We were in the living room and I stared out at the river. The view remained unchanged, but everything was different. I had no feelings, no memory, no sense of where or who I was. Time disappeared, and all that existed was the river and its tides, the buildings reflecting the sun. People moved, spoke, cried, but I simply existed. I realized that everything that was can no longer be similar to the things that will be. There was a dog-ear in my memories now – a before and an after. Stories that will come to matter will have a great absence in them. They will not be better or worse than another moments, simply different. The relief that followed, of not having to worry any more, was frightening. I didn’t know what to do with the gap that I now had. Did I fill it with sadness? Or anxiety? Or perhaps with joy and remembrance? A little bit of all of those things, like a well written play, battled each other for dominance as I stood and looked out of the window. It felt like I was there forever. Sometimes, it feels like I’m still there, watching the boats go by.

***

The funeral was held in Astoria, Queens, another less memorable borough but one of our favorites for its supreme collection of ethnic restaurants. I had very little to say, for once I was unable to form words, so instead I read Dylan Thomas’ Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night. Thomas was my father’s favorite poet. Each morning he would recite snippets of Fern Hill, interspersed with outbursts about any given article in the New York Times. I recounted these mornings to the small crowd of friends and family, a telling that was often interrupted by the black-suit-wearing funeral attendants asking us to keep the laughter down as we were disturbing other, more traditionally melancholy, wakes. The reception was held at Casanova, one of many cherished Italian restaurants, where we ate and laughed heartily into our plates tricked by the nasty habit of forgetfulness, thinking falsely that when we got home my dad would be awaiting us, and a container of left over tripe and calamari.

***

On July twenty third, my nineteenth birthday, we moved to Staten Island. The only birthday celebrations to be had were the moving men who, perched at the bottom of the stairs with our piano, looked up at me and said ‘we heard it was your birthday. You don’t have a cake?’

‘I didn’t even get a card!’ I laughed, all hollow eyes, as I watched them hoist my father’s piano up the steps.

My grandmother, who had helped clean the house in anticipation of her daughter and two grandchildren’s arrival, was seated on our couch. My mother had thrown herself into the chair. I hovered in the kitchen – it was my favorite room in the house, with deep mahogany cabinets and real terracotta tile borders on the cream counter tops.

I leaned against the doorway, watching the two women talk in superfluously hushed tones. There was no point in keeping anything secret, especially not from me. A sharp cough brought my presence to their attention.

‘–Gabriella, how did you find him again?’ My mother, the therapist, always insightful.

I knew I had made my greatest theft of all – I stole a moment.

‘He was wedged between the tub and the toilet bowl. He looked like he’d fallen while trying to fix the soap dish – his body was sort of twisted sideways. Why?’

I already knew the answer, though she never gave it to me. My mother, for all her eloquence, can’t get the detail – the cool greyness of his face, the peculiar tug at the corner of his lips, the immoveable force with which his body seemed rooted into the ground. It will always be my story to tell.

And so for the first time I felt post-pilfering guilt. I watched helplessly as a rift opened up its jaws, gaping wide with razor teeth, and devoured my relationship with my mother whole. It took years of sometimes carefully chosen words and miles of distance before the rift would shut its mouth and allow us safe passage, to place gentle kisses on each others’ cheeks in quiet understanding.

***

I resumed my habit for nicking things upon graduating college, probably in some feeble attempt at warding off adulthood. My move to England has placed this particular vice on a permanent hold, not wanting to jeopardize my visa or my freedom. My last pocketed item, stolen in mid August from the Forever 21 in Union Square, was a cheap pair of plastic sunglasses, round and black with deep rose colored lenses. My mom thinks they’re silly. She also thinks I paid for them, so I guess I’m still a liar.

* * *

‘You know, I waited outside St. Vincent’s hospital for days.’ My dad would say. He often liked to recount where he was when Dylan Thomas died. ‘I only left to go to the White Horse, because that was the only place to go that made sense… I stood outside and waited, and waited, until they finally declared him dead. And then I went home.’

We are proud to have founded the Aleksander Fund. To learn more or to donate please click here. To sign up for On being Human Tuscany Sep 5-18, 2018 please email je*******************@***il.com.