After Grace Paley

By Adina Giannelli

midrash (noun: ancient Judaic commentary or rabbinic interpretation, exposition, investigation)

She had a tendency to ask questions: to seek validation or comfort through others and their words. To inquire: should I do this thing or that? She liked reflecting on others’ insights. By reflecting she meant contemplating; by insights she meant thoughts and feelings, how they varied, how they mapped onto one another, upon her. And then, after gathering points of view, by which she meant perspectives, she liked deciding on her own. By on her own, she meant independently, which is to say, in the strength of her solitude—as she had always done. As she had always been.

When and where she asked questions, those around her volleyed questions back. These boiled down lately to how do you know this is it? She loved these questions even when they failed to reflect her, which they usually did.

Because she loved language, she knew that to reduce her love to language was to flatten it, to poison it. And much was poisoned already. So she answered insufficiently, in watered down words: she wanted to declaim, but lacked the lexicon to match her feelings’ depth. Instead, she said what people said about love: he feels like home to me; and when you know, you know; and—in a strange and borrowed idiom—she knew like the back of her hand. By hand she meant the part of her body she used to write words and lift children, to knead the pain from where it settled in his, drifting over warm skin like a nightly prayer.

Are you sure? Kelli asked, and she said yes.

Ben said you love him in a way your old ass has never loved anyone before? and she said yes.

To her sister she said I can’t stop thinking about the sound of his breath and her sister said so this is really it then? and again she said yes.

Her most religious friend said you are both children of God; never a believer, she turned her head.

On a walk with Joanne and her Samoyed, she said I want to marry this man and be with him until the end; Joanne wept; to avoid crying herself, she turned her eyes to the giant Siberian dog jumping in the snow instead.

The psychic reader she saw more than twice said stop wasting your money, this is a perfect match.

Her least religious friend said holy shit.

Jim said I know that you love him and are committed to making it work and I very much support you in that.

She was unschooled in love, and things had been challenging. Camille knew this, and found men unreliable to begin with, and she told her friend: just remember, you’re a queen, in all of this.

By remember Camille meant you’d better not forget; by queen Camille meant a woman of valor, in dominion, self-possessed. She wasn’t so sure, but she felt herself nodding regardless. A queen, she wondered. By queen she meant a person of undeserved status, someone given things she did not earn, inequitably and at others’ expense.

You want to marry him, Tara said, blinking, and she repeated yes, I want to marry him, yes, with the love that was at the core of every real yes. By core she meant heart; his; yes.

How do you know? Tara asked back. You’ve never wanted this before—you’re really bad at love—no offense.

I just know, she said, I always knew. By knew she meant him; this; yes.

You think you do, he said, and she realized everything said cast a shadow of the thing not said. She knew what was on the other side of it; this was fear. By fear she meant terror at abandonment, or harm, that she would want more, and roll out; that he was not enough. But she knew the truth in and of her heart; he was more than enough.

By more than she meant he was everything. By enough she meant BASTA!, which her Nonna shouted from the kitchen when her father acted badly, and which she painted on a sign when he left her, the last time, placing it upon her bedroom mantelpiece where a photo had once been. Enough! Stop the insanity. Enough! He was all she ever wanted. Enough! She could search the world over and find nothing greater or truer than this.

She knew that she was culpable, and she had shit to get together, if she was going to account herself to him. By shit she meant the inner workings of her mind; everything painful she had yet to unravel in herself; the things she carried. He feared that she was never satisfied. By never he meant constitutionally incapable of being; by satisfied he meant settled, focused, committed.

And while she wanted other things in the world (creative achievement; health of mind and body; deep friendship; professional success), when it came to this particular kind of human connection, she wanted only him—by which she meant them, this. It was new to her, and she was afraid of this desire, its finality and fierceness, its permanence and depth. By afraid she meant aware. Aware he had the power to hurt her. Aware that though her value never resided in the fact of his embrace, at times, the steadiness of her breathing did.

By breathing she meant the process of aspiration—not hope of achievement, but the bodily function essential to life. By life she meant her own expanse of being, who she was and what she was becoming.

By becoming she meant letting go, shedding the past and embracing the unmet future, everything she did not know, the mystery of all that would be. By know she meant understand, which is something else she meant when she said she loved him: she felt she understood him, his darkness and his light, the way he shepherded his energy; the way he let go and drew her in.

By him she meant this man whose brain was a brilliant and rapid fire. By fire she meant something that would warm and illuminate, a source of heat and light. Also: something that—if not properly tended—could destroy. By destroy she meant pull her heart from her, isolate and incinerate, or hand it back between beats. By back she meant not the side of her hand she used as an idiom, but the part of his body she curled against in the night, while he was sleeping, warm against his skin, dreaming. By dreaming she meant together. The family they’d both wanted as children, they could build, he said. By build he meant work toward becoming, hand in hand.

She loved him more anything, with the possible exception of language, which she had relied on longer and known first. By language she meant words, which were perfect in their reliability, finite, fixed. By contrast, he was monumental, beautiful, his own universe; he could not be reduced to a single word or even an infinity of words, in any or every language. She would never know all the words, and she would never, try as she desired, know all of him.

Some things remain beyond us always. Some words are not easily translatable, like schadenfreude (German)—pleasure derived from another’s suffering—or saudade (Portuguese)—deep melancholy at another person’s absence. There are no real synonyms for schadenfreude or saudade in English, she realized. And though she felt she’d experienced both, they were like all terms, borrowed: placeholders, standing in something else’s stead.

When she tried to describe the why or how of her love, or its dimensions, she ran headlong into the same lexical problem: certain feelings are ineffable, some words beyond transcription. Words were like people; there were no synonyms. He was the only one; in trying to convey everything he meant with precision, she lost the ability to wield words. Obsession notwithstanding, she lacked her own language.

A teacher once told her Eskimo people have hundreds of words for snow, you know, and while it seemed profound at the time, it was—like most early knowledge—mythological, factually inaccurate. Yupik and Inuit people do not, in fact, have hundreds of words for snow, not without redefining the meaning of snow and words. And this is true in any language.

If you can drink a root beer or a seltzer or a Shirley Temple or a dry martini, never mind an infinity of other liquids, do you in English have hundreds of words for drink? If you can read novels and travelogues and biographies and epistolary romances, to say nothing of countless other genres, does your language have hundreds of words for books?

After rolling the question around her mind, she decided after all the answer might be yes. She knew, because she found hundreds of words for love, when and where she defined it. By love she meant acceptance and commitment and partnership; dedication and patience and grace; affection and desire, longing and belonging. By love she meant the saudade of absence, the fires built in shared presence. She meant everything they had yet to reveal, all of the things they’d dreamed and knew they’d one day have the chance to enact.

By love she meant the potato boats that floated in his soup, the steam of night tea, two bodies in a hot bath. She meant the nightly return to his arms, the smell of the skin on his neck. She meant the dreams she dreamed while spooning him and the sound of his breathing as he slept. She meant two people together is a miracle, like Adrienne Rich said. She meant dancing and thank you and in sickness which is inevitable, in health if you are so blessed. She meant scraping paint chips from a hardwood floor and cleaning behind the toilet and transitional activities. She meant the epistolary romance she read to him, gladly, although it was badly written; she meant Biloxi, Mississippi and South Londonderry, Vermont; she meant his arms, around her, around him. She meant the hands she placed for comfort and relief on the small of his back.

By love, she also meant waiting, and working, setting goals and boundaries and priorities, tending to things every day. She meant babies and bodies and beds. She meant more than words, although they were her favorite thing. Love was a nice word, if ubiquitous and sometimes cheap—absent action, without teeth, bearing all the goodness of an edge. She had to make things right between them: this required more than language, it required time and trust and patience, self-knowledge and a humble heart. Love was what she did, not merely what she said. It meant making every breath a vow and a prayer and a circle of forgiveness, again and again.

She was hard, and he was hard, and so she was prepared for things to be hard, by which she meant not easy. And she wondered is love worth it, when it’s hard? There were things for which she had no words, things for which she’d never find the words. But here she had found it, for herself. By herself she meant the person she was almost, and not quite, yet and still becoming. And she knew: when love was the question, the answer in any language—a full-throated yes.

Adina Giannelli is a writer, nonprofit director, and educator whose essays have appeared in publications including Role/Reboot, Salon, the Washington Post. Adina lives in western Massachusetts, where she is working on her first book. You can find her online at www.adinagiannelli.com.

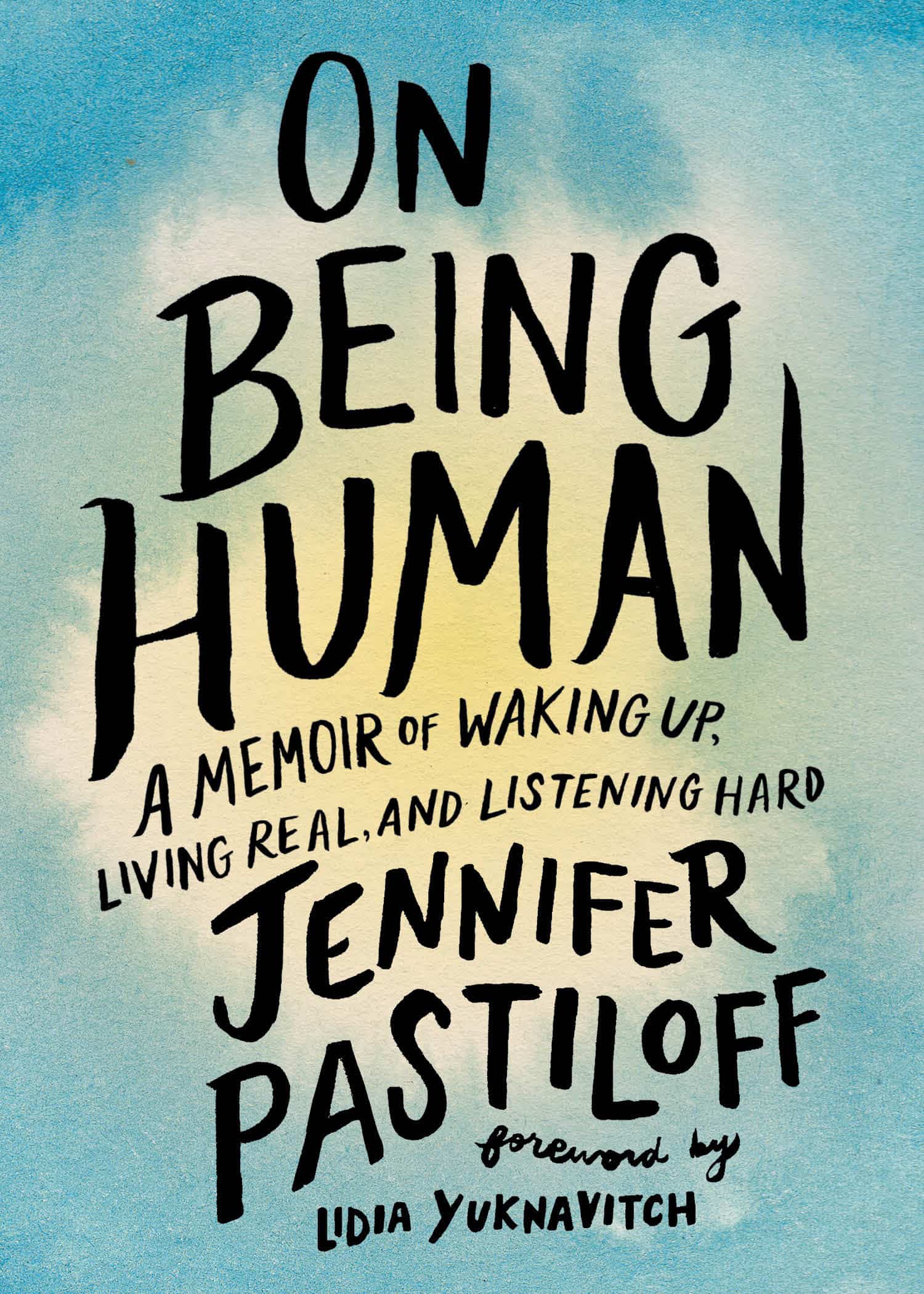

Jen’s book ON BEING HUMAN is available for pre-order here.

Wow. Yes it is a midrash, and gorgeous, and replete, with questions in all the right places, and the mandatory uncertainties to open the heart. Thank you.