By Rob Norman

I drove up to my hometown of Grand Rapids, Michigan after a very long hiatus. I cruised along once-familiar roads and arrived at the brick-paved Wealthy Street, which back in my early days, at least in that part of town, was anything but wealthy. I stopped and looked for my father Larry’s warehouse that I had worked at for many years of my youth. I found it, now quite clean and professional in appearance, in the center of a fully gentrified neighborhood.

The building was now occupied with a yoga studio called “From the Heart.” I walked in and checked it out. I made plans to take a class the next morning.

I was in town to try and find one of my brothers, Steven. Not only had we grown up in the same house, but we had slept in the same bedroom. He had written me via text (he would not speak over the phone to me or any other family member) that his girlfriend of over three decades, Cathy, was now sick with cancer and off and on in the hospital. I came up to Michigan to see what was happening.

Steven spent much of his days driving his bike around town, frequented the library, and God knows what else. He had always lived at the fringe of society, never able to gain purchase on any semblance of a normal life. As with our father, as far as I know, he never sought much-needed medical or psychiatric help and was in constant denial as to the severity of his problem. When my mother was alive, she never seemed to know what to do to help him. She would provide him food from the Temple Emanuel food bank where she volunteered and gave him cash whenever others gave her money. Time moved on and now he was in his late 60’s, still just as trapped as ever.

My niece Michelle (daughter of my deceased oldest brother Michael) drove up from Chicago to meet me, and she and one of her friends helped to spot Steven. The last time I saw Steven was five years before when I brought my oldest son Daniel with me to a high school reunion. Steven and I sat and talked for a little while on the porch of the apartment he was sharing with Cathy. He could only talk about the past, his words infused with a fierce nostalgia. It was like observing someone who could only walk backward and never forward. He limited his talk to reflecting on shared memories of childhood but nothing about the future. Perhaps the past kept him moored to a known mental shore during a time of continual rough seas. I knew that now, given what Cathy was going through, he probably felt a very tenuous hold on life, even more ephemeral than ever before.

The next morning, I arrived early for the yoga class. I went in and paid my money for the class. My mind flashed back to enormous piles of used auto parts–starters, generators, alternators, brake shoes, and others—that rose up almost to the ceiling throughout every square foot of the building. Narrow, grease-stained passages had allowed access to certain sections. The twisted towers of old iron parts—rusty and masculine–all smelled of family responsibility and the scent of trying to please my father.

The yoga instructor, who introduced herself as Eleni, was quite pleasant and professional, and I found myself surrounded by about two dozen avid students. We began seated on our mats. Breathing exercises were followed by various stretches, and my body began tuning up like the motor of my old Ford Mustang on a cold Michigan winter’s day. We began to clear our minds with the relaxation techniques of pranayama, alternating breathing in and out though each nostril. “Time for us to mentally detox,” the instructor said.

I thought about how hard I had worked inside this place for my father over many years, beginning at about ten years old. I could remember the thick smell of the asbestos-lined brake pads, grease-filled drum brakes, and clutch assemblies.

Yoga comes from the root yug in Sanskrit like “latch on or hitch on,” usually meant for a horse, as in attaching horses to a vehicle, but I believe we can use the practice as a vehicle for hitching onto a journey into the self.

At the end of each work day, when my father drove his big red box truck, emblazoned with Grand Rapids Exchange Company on the sides, down Burton Street and turned towards our home, he would slow down, turn on the lights and slowly make his way to our driveway. He would usually get the food that was on the stove that my mother had cooked and bring it upstairs with the day’s newspaper. He poured himself a bath and put in Epsom salts. He locked the door and stayed in there for hours. When everyone had gone to bed, he went downstairs and watched TV all night.

“The ultimate goal is liberation from the Self or Ego. To achieve transcendence requires practice and dedication. A key is the ability to meditate mindfully, letting thoughts come and pass through, and stay focused on your practice and the moment,” Eleni said.

I don’t know all that has affected by brother Steve, but I do recall one incident that was a game-changer. Each year a professional basketball team came to town for an exhibition game and 1970 was no exception. In addition, it was my 15th birthday. As I prepared for an exciting day ahead, I started feeling a pain in my right lower side. I tried to wave it off, but it grew in intensity. At a certain point, I was doubled over in pain.

“Exhale to bring your hands to Anjali Mudra, the Salutation Seal, in front of your heart. Now inhale and come to the balls of your feet. Sink your hips down slowly in the direction of your heels. Exhale.”

My father was in the bath, and my mother pounded on the door for him to come out. She did not drive at that time and was dependent on him for transportation. My mother said, ”Robbie is sick! He’s got to go to the hospital.” He refused to come out, grumbling and making excuses. She kept trying with no response. Finally my mother’s sister—my aunt Shirley—came over and drove me to the emergency room. My appendix was hot and bursting and I was in surgery within an hour. Steven, three years my elder, was privy to all this insanity. He never spoke to my father ever again after that night.

“Come to a resting position, legs crossed. Now hook your left elbow outside your right thigh, pressing your palms together. Hold for 5 breaths, then exhale and unwind. With each inhalation and exhalation, say ‘My body is strong and stable.’ Now repeat on the other side.”

I looked out the window at the neighborhood. The overwhelming scene was modern urban renewal and I wondered where all the residents I had seen decades ago now lived. The malls had melted away. Food and beer joints had swept into every town in America as if they were new discoveries. Anyone with money could order almost anything online. Yet yoga was still a candle in the window that drew people together.

Eleni spoke with vigor and passion, conducting the orchestra of movement. “Come to Tadasana the Mountain Pose. Inhale, and raise your arms perpendicular to the floor with palms facing inward.”

The sweat and sinew and Sanskrit incantations of Yoga mixed with the recollections of moving scrap metal from the truck to the warehouse and back again. I worked year round—from the coldest days with snow piled half way up the warehouse windows to the sweltering urban heat of an August afternoon.

“Come to Tadasana. Shift your weight slightly onto your left foot. With each inhalation and exhalation, say ‘My body is balanced and beautiful.’ Now let’s repeat on the other side.”

I helped move auto parts from the warehouse to the truck. My father helped a little, but by his late 40’s his back had already been beat up enough that he required heating pads and supine rest for hours every evening. I never remember him getting an x-ray or any kind of diagnosis, just as he never went to a shrink or anyone that could place all his crazy signs and symptoms into a tidy title. Today we are obsessed with names and syndromes, with the DSM on an app on our phone. In those days they just called him “Crazy Larry” and that seemed to cover it all. Others labeled him manic-depressive, schizophrenic, and pasted on other diseases. Many seemed enamored by his boyish charm and manic energy, but overall he was pretty nuts. He seemed to live in a no-man’s land between contrived autobiography and fiction.

“Kneel on the floor. Exhale, and lay your torso down between your thighs. Reach your hands out in front of you, resting your forehead on your mat,” Eleni said.

I still remember the sizes and shapes of all the auto parts more than 50 years later. Auto parts were everywhere, the currency of keeping a roof over our heads. Even our basement and garage at home were filled with auto parts as if every piece was a precious jewel. One time I dropped a 3250 generator (rectangular box) on the stairs as I was bringing up auto parts from the basement to load into the truck. He said, “Be careful, that’s worth more than you.” In the evening he would hand me a list of rebuilt parts to get up from the basement to put on the steps to get ready for the next day’s truck load to go out.

Eleni said, “Turn onto your back. Flex your feet and hold onto them from the outside as your draw your knees downward toward your armpits. Roll side to side a bit on your sacrum if it feels good.”

Happy Baby Pose, I thought. Ananda Balasana. Are all babies really happy?

“Resist the urge to put your toes in your mouth. After five breaths, stretch your legs out on the floor and rest,” Eleni said.

One day my father drove his truck in the backyard and left it there, filled with auto parts. He got a pick-up truck to use and the truck became another storage unit and another place to work. My brother Howard had painted a pink peace sign on the blue basketball backboard, a piece of weird art in a weird life. Vietnam was in full stride and we had neighbors, the ones who made it back, returning physically and mentally wounded and with horrific stories. My brother Mike had become a young father and stayed in college to avoid the draft.

“Come down onto your hands,” Eleni said. “On an exhalation, feel a comfortable stretch in the front of your left thigh and groin.”

In the summer the bookmobile would come every week to the neighborhood, a couple blocks from where we lived, and provided a wonderful respite from my father’s pedantic, odd syllogisms, my mother’s anxiety and depression, and the overall claustrophobia of home. I remember the smell inside—the smell of books, as if it was palpable and I could slice a piece of it. Books gave me a chance to live other lives, to go on wild and wonderful adventures in my mind and explore the uncharted universe.

“Think of the power of your words,” Eleni said. “If your inner dialogue is repeatedly negative, it can feel like you’re listening to a broken record. Self-defeating thoughts can wreak havoc on your self-esteem,” Eleni said.

I thought about my father, who seemed to possess a volitional ability to feign ignorance for most obligatory tasks in life such as maintaining a home, family, and moral responsibility, and exhibited little in personal awareness, relationships or conversations. His main verbal obsession was saying “Do as I say, not what I do,” as if that could make up for showing examples of being a mensch in life.

Eleni bent down. “Exhale, and bend your knees to come into Utkatasana, taking your thighs as close to parallel with the floor as possible. Allow your weight to rest in your heals.”

My father believed that if you followed all his verbal instructions the world would somehow be perfect. All of his edicts, although mostly constrictive and paranoid, would lead to a highly successful and rich life. You could have a life spent sailing on your private yacht on the Mediterranean Sea and money flowing like water, fully aware of every possible option and always making the correct decisions. However, the intention of each of his soliloquies was soaked in the impossible and unattainable world of magical thinking. Although the outside scenery of his imagined world could potentially have flashes of brilliance, it would not be perfect, obvious by a lack of the internal integrity of a life well lived by continual introspection and trial and error. As Robert Frost said, “the best way out is always through.”

Eleni spoke with firm conviction. “Repeat positive words or phrases and start to shift into a healthier state of existence. The more you practice, the more you’ll be able to speak to yourself as the divine being you are.”

My father’s obsession with money seemed to be a mix of a childhood lived during the depression and his orphan upbringing. He behaved as if money was the key to all success in life and fueled his every thought. He displayed a sycophantic compliance to those who supplied him with used auto parts, which became even more exaggerated with those who bought from him. I found later he had hoarded cash and had little tolerance for keeping financial records. I knew he had never spent a penny on pleasurable vacations or creature comforts, especially with my mother or his children.”

“Thank you for joining me today in your practice. Thank yourself for taking time to allow yourself to just be in the moment. Before we leave, let us chant. The word AUM is not invented by any man,” Eleni said.

As we all chanted, I wondered if it was actually possible to just be in the moment and withdraw from the world. We are creatures of such powerful personal and atavisitic histories and swirling, biochemical, cerebral explosions. I thought about chanting AUM in a place that I had heard another kind of chanting decades before–my father’s constant and oppressive aphorisms. Instead of any conversations in which feelings and ideas were exchanged, he chose to spout out staccato phrases that he apparently thought held the most essential keys to my ongoing survival—”Wear your hair short, Keep a list, Learn a bone a day (to learn medicine), Check behind.” At times his utterances were truly frightening, such as “Kill anyone that gets in your way.” All of these, which still echo in my mind, had made me feel like a down dog. The karma of what was happening was highly unnerving.

Eleni smiled. “Acknowledge the gift of energy and time you have devoted to your practice today. The Divine in Me honors the Divine in You and through this we are One. May all living beings everywhere find peace and happiness. Namasté.”

The moment I left yoga, Michelle called me on my cell phone. “We saw him,” she said. “Come meet us.” She guided me to the place that she had last seen him and we waited for him to reappear. A rare bird, the only one of its kind, and we had him in his natural habitat.

Steve looked ragged and worn and frightened beyond his usual hysteria. He was angry and paranoid and saying “I’m OK.” He had long unkempt hair on the back of his head and wore a felt hat that covered his balding front. He just kept telling us, “Leave me alone.” Apparently he was living with Cathy and had a roof over his head. Michelle was there with me which was good to have some support. I had called my brother Howard in Vermont to give him a scouting report and keep him informed.

He appeared to be in very bad shape, struggling both physically and emotionally. I looked at his bike, a simple vehicle with an oversized basket on it. “Hey Steve,” I called out. He would not get off his bike to talk. I did not like using ambush tactics to see my own brother. Michelle offered him some cash. I got out of the car as he took the money.

I walked over to him, gave him a hug, and told him I loved him. Part of me wanted to punch him out of anger because he was so inaccessible. Put the wounded animal out of his misery.

I could smell the street on him, and knew he was not keeping up good hygiene or eating properly. He took back off down the street. I knew that after I returned home, he would continue to text me and ask for more help.

I was frustrated; I was in need of conversation with my brother, and I knew it would not happen. Mental illness had once again tipped the scales so that Steve had become the epicenter of profound neediness and I was a peripheral character. I wanted to have a reality check as to how he was doing. I wanted to be a grief sponge, a natural brother, and listen to his problems, having pondered daily how his daily life was going. Given his behavior, I was a bystander, an oxygen thief in a world I could not control.

Repeat my peace-filled mantra, I thought, and imagine its meaning permeating every cell of my body. Breath out all worries. Breath in and soothe my soul. Man, it’s tough.

Dr. Robert A. Norman is a board-certified dermatologist and family practitioner who has been in practice for over 30 years. He is a faculty member for several medical schools (Clinical Professor) and has been honored with numerous service and teaching awards, including Physician of the Year (2005) and Distinguished Service Award (2007) in Hillsborough County, Tampa, Florida, Tampa Bay Medical Hero Award (2008), and the Hadassah Humanitarian Award (2012). Dr. Norman has written 41 books, including The Blue Man and other Stories of the Skin (University of California Press) and Discover Magazine’s Vital Signs–True Tales of Medical Mysteries, Obscure Diseases, and Life-Saving Diagnoses. He has been the editor and contributing writer of 15 textbooks on Geriatrics and Geriatric Dermatology and published over 200 articles in various major media publications. He is a frequent medical volunteer. His most recent medical mission trips were to Jamaica. Other trips have included Haiti, Guatemala, Cuba, and Argentina.

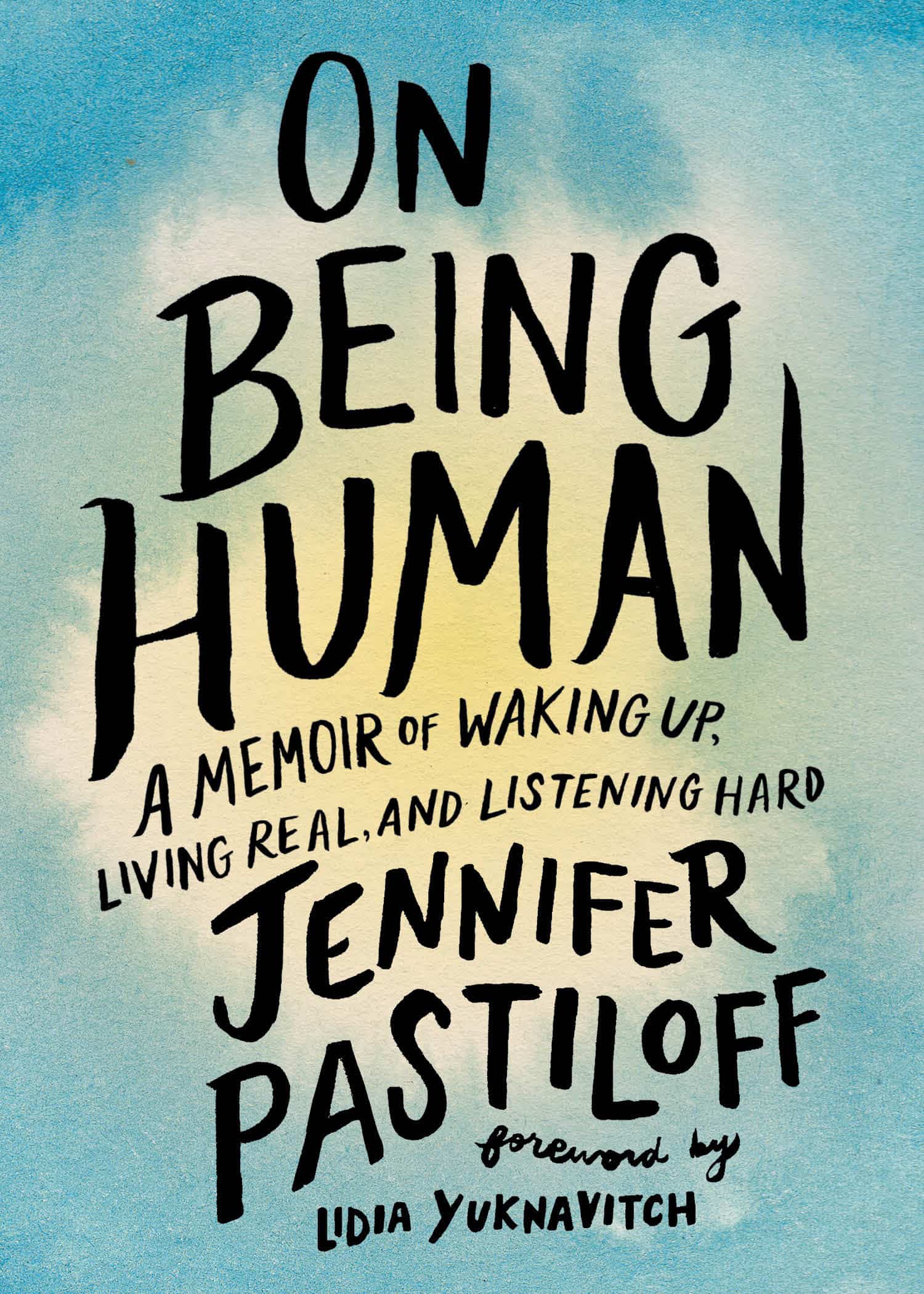

Jen’s book ON BEING HUMAN is available for pre-order here.