Drained

I cannot see her beyond the hospital curtain that separates our spaces in Tower Med/Surg. Her bed is near the door; mine is in the back by the bathroom. But I hear her. Her whole story. A spiel she has practiced. Trace of a New York accent used on the phone with her one friend. With the nurses and doctors. With anyone who comes into the room. “How long have I been here?” she asks when she returns from dialysis.

The tech taking her vitals says, “Two weeks.”

“My cleaning lady found me unconscious on the floor of my townhouse,” my roommate explains. “I live in a 55+ community. I don’t remember anything about it.”

“How could you?” the tech asks. “You were unconscious.”

My roommate continues talking. “My husband and I adopted a son and daughter from an orphanage in Uzbekistan. We raised them together for eight years, but when my husband and I split up, the kids wanted to live with their father because he had a rich girlfriend they could sponge off of.”

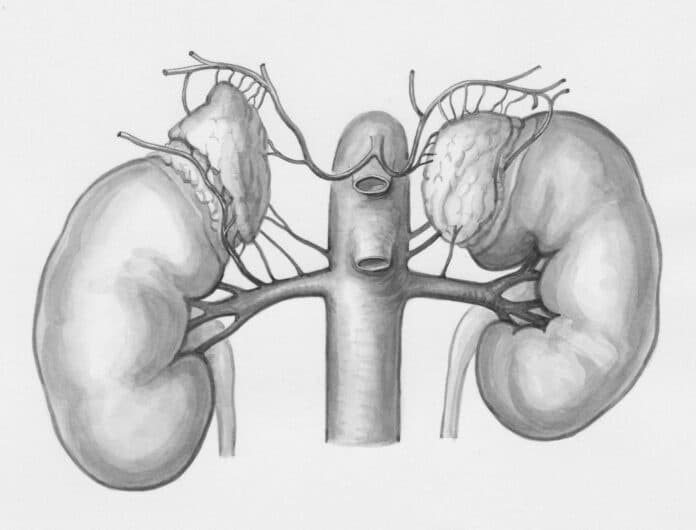

I also learn she’s had diabetes for forty years and she’s in kidney failure. Her family history and mine have that in common.

Her son, now thirty-eight, has been packing up her dishes and took her checkbook, so she tells her friend on the phone. She complains about my cell phone pinging. She complains I get more attention. She complains that she’s drained, and of course she is because that’s what dialysis does. She wants to die. She’s on dialysis. She is going to die.

Dialysis is the beginning of the end. I base this opinion on my father’s experience.

She shares with her son that he’s been seen hanging out with the community security guards. She thinks he’s going to clean her out. She is drained of life, depressed since her parents died. She is terrified of transferring to a rehab facility where she’ll be even more ignored. She wants ear plugs, because noise bothers her. The last place anyone can rest is in the hospital.

I want to tell her she is delusional. I am not receiving more attention. I don’t expect any attention except when I use the call button to alert the nurse that my IV is beeping.

The son comes to visit. I cannot see him, but I hear him. They fight. Neither is yelling, but their words are scalpel-sharp. She wants him out of her life. I can sense frustration from both of them. He leaves. I imagine he slinks out of the room, telling himself he tried. I imagine she slinks down in the bed, telling herself she tried.

I cringe when I hear her order all carbs from Food Service. She says no one has ever given her any counseling. I don’t believe that. Counseling is one of the first consultations scheduled when you get a diabetes diagnosis.

The phone rings. It is her son. She tells him she wishes him a good life, and she hangs up the phone. She is all alone except for the friend who told her about her son cavorting with the community security guards, and about the missing checkbook. She tells her friend she wants the locks changed on her house. It’s hard to think rationally in the hospital. It’s far easier to lapse into deep despair, to tell yourself the world has forgotten you, even the nurses who don’t respond to your call button.

Inheritance

I inherited the family’s diabetes condition twenty years ago. I am in the hospital for cholangitis, a stent installed during an endoscopy to drain the e. coli infection. I’ve already been challenged by my 2022 diagnosis of the rare, incurable pemphigus vulgaris, an autoimmune disease that afflicts Eastern European Jews. I watched my father’s decline, his loss of appetite, the loss of color from his face. How he dragged his body up the stairs and into bed during two years of dialysis, his drained heart eventually stopping. If I don’t manage my diabetes, this could be me in my seventies. That’s only a few years away.

Dialysis is the beginning of the end.

My Soviet émigré husband and I had our son in 1989. Two years later, we split up, his undiagnosed ADHD and anger management issues flaring up from time to time: chasing me into the street waving a butcher knife, throwing our son into the kitchen cabinets, punching holes in the walls, smashing my toaster with a hammer. Our two-year-old inherited his father’s ADHD and anger. By the time he was ten, I had to place him out of district and by the time he was fifteen, I had to stage an intervention, put him in an outward-bound program in West Virginia and then an at-risk residential high school in Upstate New York.

My son, now thirty-five, comes to visit me in my hospital room from Long Island, where he lives with his wife and two little girls. He says, “You know we have to talk about this. You need to move to Long Island so I can take care of you.” In this moment, I know I raised him right. All those times I read him that blue paperback, Love You Forever,” that book with the cover illustration of a toddler boy dropping a watch into the toilet bowl. That was my son to a tee. But now all he really cares about is being a good husband, father, and son. He wants to be the father he never had.

After he leaves, I am on my phone all afternoon. I ask a work colleague at the community college where I teach in the Liberal Arts department and am director of the Holocaust, Genocide, & Human Rights Education Center to pick me up and bring me home. I talk with my niece’s husband, a doctor of PT, to make sure going home and not to a facility is the right move. He agrees. I feel grateful I have a network of friends and family to rely on. I contact a private home health agency and arrange for two weeks of service.

I wonder what my roommate might think of all these conversations.

Twenty years ago, I staged an intervention and placed my fifteen-year-old son into an Outward Bound program and then transferred to a residential at-risk high school. At fifteen, he hacked into my credit card accounts. I had to refuse all UPS deliveries, including a seventy-pound motorbike my son ordered. He overdosed on Coricidin. Brought up on burglary charges. Probation and community service. I hired an educational advocate to find my son a program. At the time, I was working for a high-technology company. I hated the work, but the money was great and allowed me to pay cash for all the help my son needed. He thanked me, eventually, for saving his life.

My son and I have come a long way. I raised him by myself since he was two. His happiness is my biggest accomplishment. Before my discharge from the hospital, I go online to check out one-floor homes in 55+ communities in Suffolk County. We will need a real estate agent.

***

***

The ManifestStation publishes content on various social media platforms many have sworn off. We do so for one reason: our understanding of the power of words. Our content is about what it means to be human, to be flawed, to be empathetic. In refusing to silence our writers on any platform, we also refuse to give in to those who would create an echo chamber of division, derision, and hate. Continue to follow us where you feel most comfortable, and we will continue to put the writing we believe in into the world.

***

Our friends at Corporeal Writing are reinventing the writing workshop one body at a time.

Check out their current online labs, and tell them we sent you!

***

We are looking for readers with an hour or so a week to read non-fiction submissions.

Interested? Let us know!

***

Inaction is not an option,

Silence is not a response

Check out our Resources and Readings