By Amy Tsaykel.

In the midst of a glaring summer, I see only black. I’m striding through aisles of colorful, racked clothing that normally might provide hours of distraction—but today I am focused. Not even my girlfriend who part-times at the outlet mall can regale me with her usual gossip. I’m on a mission, I explain, for a funeral dress.

I must be absolutely perfect for my grandfather.

Granddad was 91 years old when he decided to stop treatments for leukemia. Precisely according to his wishes, hospice was called, along with the longtime family minister and his five children. We all agreed that he was lucky to pass so quickly. Grace, dignity, and good fortune—the hallmarks of Granddad’s life—reigned until the very end.

Mom called me to deliver the news and was, amid her mourning, surprisingly pragmatic. She and her siblings had (per their father’s wishes) already been sorting his belongings. What did I want, she asked: hand tools? whiskey tumblers? One of his paintings?

“Clothes,” I replied, without hesitation. Why?

When I think of my grandfather, I think of his business suits and polished leather loafers, befitting of a hardworking utility executive. I think of his church choir robe, pristine white. Sometimes he’d lift his voice amid a crowded family gathering, and soon we’d all be singing.

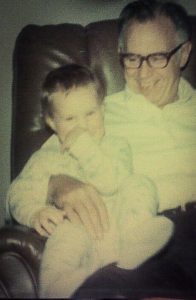

His favorite cardigan had arm patches, sewn and sewn again by my grandmother. There’s a picture of him in that cardigan, lounging in his favorite recliner and holding my infant self with outstretched arms.

For carpentry work, he had a wardrobe of plaid button-down shirts. He could raise a roof as easily as turn wood on a lathe. He designed and built no less than four family homes, and crafted countless pieces of furniture, including a wooden artist’s easel that is my treasure. Days before he died, he rode out to his son’s farm to witness the raising of a pole barn he’d helped design. In his lifetime, Granddad solved many such puzzles, bringing beauty into the world along the way.

Beauty, however, is not all I am seeking in these racks today. I am not seeking the cutest dress, or even the most flattering. I am seeking something respectable—something Granddad would find appropriate. Dead or alive, the man holds an approval for which I am keenly, unapologetically aching.

If I were a stranger passing on the streets in Midtown Atlanta—perhaps some sunny afternoon on a sidewalk in Piedmont Park—would he nod a friendly hello? If I were a midcentury stenographer at Georgia Power Company, where he was longtime VP, would he offer me a raise? And if I were a new member at Peachtree Road Lutheran Church, where he helped found an elementary school, would he invite me over for a welcome supper?

Moving from shop to shop, I feel anxiety mounting and guilt rising: Surely it’s materialistic to spend the day after a loved one’s passing in a dressing room. Is this what mourning looks like in 21st century capitalistic society?

My anxiety is driven by this undeniable fact: I cared what this man thought of me. To my own chagrin, I’ve cared what countless other men think of me. This stark truth makes me feel even more vulnerable. Hopeless, I think, slinking out of Brooks Brothers and into the food court for a chocolate fix.

My grandfather was infinitely competent. Often, I have feared that I am not.

* * *

The summer that I turned 11 years old, Granddad got a new riding lawn mower. My brother wanted to drive it, so I insisted on a turn at the wheel, too. Granddad granted me permission to steer it down the hill and into the garage.

I remember the exhilaration of being granted such responsibility. I remember hearing the engine gunning over instruction from Granddad and Mom, both following me on foot. I remember perching atop the black vinyl seat, feeling like a summertime queen, cloaked in a heady haze of exhaust and humidity.

I don’t remember blacking out, but yes—that’s what happened. I awoke to a crash as everything in the garage fell into a heap, covering me and the wayward mower.

All but my dignity was unharmed. To my brother, I was a laughingstock. To Granddad, I was far better off in the kitchen, helping Grandma with the biscuits. To all of them, I couldn’t be trusted. Yet there was something that none of us knew:

I’d suffered from a mild seizure. It wasn’t my first, and it wouldn’t be my last. I would soon be diagnosed with petit mal epilepsy, which has since grown into a more complicated form.

It was not an easy year. Strange and alarming things kept happening. In the midst of animated conversation, my words would trail off and I’d gaze absently into space. Or, I’d be keeping rhythm in a dance rehearsal and abruptly stop moving. My dad started calling me “air head”; friends told me to snap out of it. Teachers watched my grade average dip from A-plus to B.

After my diagnosis, the stress eased a little. Supposedly, we now understood why I’d been acting funny: Neurons were misfiring. It’s not your fault, I was assured. My brain was just broken. I am broken.

Yet my quirky behavior remained a source of frustration. I still felt spacy, later realizing it was a side effect of my medication. In college, I accidentally drank myself into a grand mal seizure. Years later, standing on the subway platform in San Francisco, another seizure nearly sent me tripping into the tracks. When I married, I felt like a burden to my husband—an accident waiting to happen.

Certainly not all my failures and shortcomings can be conveniently pinned on epilepsy. When my marriage finally did fail, I was living thousands of miles away from any family, but could feel the echo of my family’s disapproval. Granddad had stayed married to my grandmother for sixty-five years. I had barely made it five.

I am broken.

“You care too much what other people think,” Mom has told me since I was a child. She is right, as usual. Yet dare I discount the opinion of her own father? What was that opinion, anyway?

* * *

I carry these weighty thoughts, along with my half-melted leftover cookie from the food court, into one last boutique. Kenneth Cole is an unlikely place for an epiphany. Yet that’s where I see the dress—the one that reminds me of Hazel.

Hazel was the lively, bright-eyed woman whose affections Granddad sought after my grandmother died. Hazel was a painter (as I’d once aspired to be) living on an island off the Georgia coast. He called her “my little pink pill” because she raised his spirits in a dark time.

In their mid-eighties, the two wed. At the time, my own marriage had just severed. Granddad’s love for Hazel bastioned me, reminded me that rebirth is always possible with an open heart.

Their union also challenged that vaguely haunting fear that had long assumed Granddad disapproved of me. If Granddad could understood Hazel—a woman who felt like my soul sister—then maybe he understood me, too.

Although the dress at Kenneth Cole is a cookie-cutter piece (surely sweatshop-sewn) it intrigues me. It is whimsical, romantic—like Hazel. Its layers of transparent chiffon are nothing like the ordered, predictable life Granddad led most of his years. Is it respectable enough? Suddenly, I’m not sure it matters.

The salesman is nearly ready to package it for me, but I have a better idea. No thanks, I tell him, I have what I need.

The search is over. I go home and open my closet: I have everything I need.

I pull out a gauzy oversized black shirt with a streamlined pencil skirt. I find the fake pearls that Granddad’s mother had crocheted into an elaborate necklace to adorn herself during the Great Depression. I add my grandmother’s cameo ring. I wonder what Granddad might think of my cream-colored lace tights—too racy?—but shrug my shoulders. Don’t I get a say in this?

I stand toward the mirror and tentatively lift my gaze. I am loved. Dressed at last, I feel this truth rippling through generations, enveloping me, soothing my grizzled heart. Then I turn to say goodbye.

* * *

As I pack to leave Atlanta after the funeral, Mom adds a few items to my suitcase: his plaid work shirt, his leather jacket, his lambswool cardigan. I lift each item to my face and inhale, allowing the familiar scents to whisk me through time: I’m in his woodshop, watching him build toy trucks for his grandchildren. Now I’m in his minivan, being chauffeured to a Braves game. Finally, I’m back in his arms as he lounges in his favorite recliner.

I am wrapped in warmth. He is beaming, and so am I.

Featured image photo: mamnaimie/

Excellent article Amy! Everytime I walk in my garage I think about grandad and look at his old band saw. I can’t bring myself self to use one of his old chisel though, afraid I will break the handle I’m sure he turned on one of his old lathes.

Amy – Off the charts! You captured the essence of how I think we all feel about him … and … I can guarantee you that he always did (and still does) very much approve of you!

That’s beautiful, Amy, and I will echo what Bill said – not only did he approve of you, but he considered you, and all of us, as absolute, unqualified blessings! In fact, of all the things I’ve learned from him and my mother (and Hazel, too, for that matter), maybe the one that stands out most is to see our lives as gifts and the people in them as blessings.

I totally understand the part about trying to live up to something, though. He was the epitome of “the greatest generation”. He lived life to the fullest (though in a pretty well-behaved and responsible way), and didn’t complain about the bumps in the road; he just dealt with them and forged ahead. He set a really high bar for us. Notice I didn’t say he imposed it on anybody; he just lived to high standards of his own. I often feel like I can’t match it, but I try, for him as much as for me.

Some of the last words I said to him (a few minutes before he moved on) were, “We’re going to live a good life”. Live your own “good life”, and I know he would approve! 🙂

This article made my heart soar….you are blessed! Thanks so much for sharing this most excellent sweet story!

Wow, Amy! Deeply felt and beautifully written. You remind me yet again what a blessing it is to belong to this family. The unconditional love that we experienced from Grandma and Grandad keeps shining through in every generation. Thank you so much for sharing this.

I echo the comments above. Thank you for sharing this. As you know, even as an “in-law” I claim this family as my own and it is a privilege to be a part of it. Everyone is so loving that we all feel loved.

Amy , this is a beautiful, loving tribute. I know Uncle Bill would be so proud. I also know your Mother must be so happy that you have this amazing love for your grandfather. You are blessed and you are a blessing.

Amy, this warms my heart on a cold, cold Atlanta night.