By Tara Ison.

an excerpt from Reeling Through Life: How I Learned To Live, Love, and Die at the Movies.

I had my first experience with electroshock therapy when I was eleven.

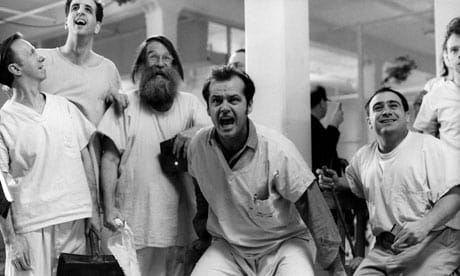

It was 1975, the year I started seventh grade, and boys my age were strutting their Crazy Jack Nicholson imitations from One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest all over school.[1] I know I saw the R-rated Cuckoo’s Nest it when it opened in a theatre, and I know some adult must have accompanied me – my parents, or an indifferent babysitter, although why would anyone take an eleven-year-old girl to see such a movie? – because I was too timid and well-behaved to sneak into verboten theatres on my own. I didn’t break rules; I was scared Something Bad would happen, that vague threat if you somehow sullied your permanent record by misbehaving, by acting out.

In Cuckoo’s Nest, Randall P. McMurphy, aka Crazy Jack, is a charismatic petty criminal who tries to evade prison by feigning craziness, which he thinks will earn him some easy time in a mental ward. Doesn’t work out to his benefit, in the end. The film was shot in the real Oregon State Mental Hospital in Salem, and looks it – some of the zombie-like extras with deformed craniums seem too creepily real. Lots of metal doors clanging, chains clanking, images of leather restraints installed on cots, and stooped men with shaking hands. At eleven, I feel haunted and creeped even as I watch from the safe distance of my theater seat, even as I tell myself it’s only a movie; when the dazed and confused patients line up to get their little Dixie cups of pills and water, I can almost smell that thin wet-paper smell as they swallow.

Bad-behaving McMurphy comes up against Nurse Ratched, the white-stocking’d, sexually repressed, modulated-voice, emasculating image of the Bitch in Charge; when McMurphy boasts to an orderly that he’ll be getting the hell out soon, and the orderly grinningly tells him “You’re going to stay with us until we let you go,” McMurphy, for the first time, realizes he’s trapped – that Nurse Ratched is truly in control of his destiny, his body, his mind.

What haunts me the hardest, then and now, is the scene where McMurphy, after inciting a near-riot, is given electroshock therapy. He isn’t wheeled into the small white procedure room, strapped to a gurney – no, he strolls in, with that cocky Nicholson bounce and grin teenage boys love to emulate, oblivious to what’s in store. When he’s asked to lie down on a table, he cheerfully complies. My heart starts racing around here – I know what is coming, I believe, but I don’t know how I know, I just know in my belly it is the punishment coming, the Something Bad. I am too old to look away, to seek the comforting glance or hand of an indifferent adult. McMurphy’s shoes are removed; conductive gel is smeared on his temples, and I feel the pasty chill of that on my own face. He obligingly takes into his mouth a rubber guard that looks exactly like the dental plate my orthodontist uses to take impressions of my teeth for braces. Attendants place padded white tongs on either side of his head and grip him under his chin, a flip is switched, and there’s a brief, brief buzz that isn’t the worst of it – it’s the seizing up and sudden clench of McMurphy’s body, the whine from the back of his throat, the convulsive shaking and straining he does for long moments after the shock itself has ceased, the way everyone has to struggle to hold him down. I watch that with my pulse racing, my fingers gripping the armrests hard, my own body in some kind of mimicky, rigid seize.

Earlier in the film, at McMurphy’s admissions interview he told that prison officials, in fact, suspect he might be faking his craziness, and they want an evaluation whether or not he’s really mentally ill. The evidence he’s nuts: he’s “belligerent, talked when unauthorized, been resentful in attitude toward work in general,” and that he’s “lazy.”

You hear that when you’re eleven years old, you see where Breaking Rules can get you.

An Italian neuropsychiatrist in the 1930s, Ugo Cercetti, was studying the link between epilepsy and schizophrenia, and that research, combined with a slaughterhouse visit where he watched panicked pigs electrocuted to docility just before getting their throats cut, sparked the idea of that zapping electric shock as a form of psychiatric treatment. By 1940 electroshock therapy was the new Holy Grail of convulsive therapy; it reached a zenith in the early 1950’s (see: Sylvia Plath), then began a slow tapering downward during the development of anti-psychotic drugs. The practice hit its nadir in the mid-to-late seventies, but a 1985 conference of the National Institutes of Health acknowledged its efficacy, and electroshock – now referred to as ECT, electroconvulsive therapy – is back on an upswing

But whichever side you’re on: it’s tough to find an article or book on electroshock therapy written after 1975 that doesn’t reference One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest. That image smacked both culture and science hard. Scientists weave discussion of Randall P. Mc Murphy in among actual case histories of real people, and words like hypothalamus, cognitive dysfunction, neurotransmitters, and joules.

But for me, at eleven, it isn’t a cultural phenomenon; it’s simply the most brutal, cautionary thing I have ever seen. It’s the iconic electric chair that bursts a prisoner’s head into smoke and flames. It’s the cop’s stun gun shocking the belligerent perp; it’s the blue florescent bug zapper that fries any creature that stings. It’s bang, bang, Maxwell’s Silver Hammer coming down upon your head, it’s the throbbing cartoon thunderbolt of agony stabbing the brain in aspirin commercials. It will be the time, later, when I am fifteen and working in a bakery, that one of the older guys in back tells me to Put your hand, here, on the metal side of a dough-mixing machine, and OK, now grab on to this post, and I do, and I hear the burr as all my marrow jerks up hot and vibrating, my jaw snaps, the roots of my teeth begin to burn, and every thought I have ever had of owning myself is for a flash seared away. It’s the imagined whiff of cerebral scorch. It’s the image of cocky, swaggering, feral Jack Nicholson reduced to an electrode-wired animal in a cage and temporarily made meek. It’s the terror of that one day happening to me, if I ever step out of line, am ever not a Good Girl, ever become belligerent, ever talk when unauthorized, ever appear resentful in attitude to work in general, ever become lazy.

Because most of all, I learn, it’s something people in power can do to punish you.

I had a blind Aunt Edith, one of my grandmother’s six siblings. As I child I saw her on holidays and the odd family occasion when we’d all go out to a formal Chinese restaurant. I remember her as pleasant and smiling and dull, a well-groomed aging lady in a boxy suit and careful bouffant who smelled of Aqua Net and fruit Lifesavers and gave crisp five-dollar bills as presents. Most of the time she would be perched on the couch next to my grandmother, who brought her miniature quiches and cocktail dogs on a napkin; it was my job to escort her to the bathroom once or twice during an evening, where, always forgetting, I would lean in to turn on the bathroom light for her and then be embarrassed at the lightswitch click.

My mother and I would visit Aunt Edith at her Miracle Mile apartment, and I was amazed at how tidy it was, every knick-knack in place. Once I remember Aunt Edith talking about a book she was writing, the story of her life, and she waved a thick sheaf of neatly typewritten pages at us. She had big big plans for it. I remember an unusual spark in Aunt Edith that day, an off-kilter excitement that seemed unusual for her. A simmer that somehow made me uncomfortable.

My grandmother was Edith’s lifelong caretaker, even after she married my grandfather at nineteen. And Edith needed caretaking – in her twenties she began showing signs of manic depression: during wild upswings of energy she’d get angry and mean, or ramble about the big big plans she had for her life. She’d also hit the bars at night, picking up men and having a lot of sex. She’d make incoherent and frenzied phone calls to my grandmother in the middle of the night. She was robbed and beaten up at least once; she might have been raped. Then she’d crash and disappear for a while, to my grandmother’s despair and panic and perhaps my grandfather’s relief. She’d return, apologetic, brushing off concerns, picking up her life, and all would be fine. Then the mania would start again, the upswing of frenzied partying and sex, the shrieking, volatile phone calls – my grandmother was terrified Edith would get herself killed, and my grandfather became increasingly resentful at being Edith’s Caretaker, the role he inherited when he married my grandmother. It was during one of these manic periods that my grandfather decided to commit Edith to the mental institution at Camarillo State Hospital.

Mondays through Fridays, everyday at 3:00, my local ABC station used to run “The Afternoon Movie.” I’d come home from junior high and heat up a Stouffer’s Tuna Noodle Cassarole, open my algebra or history book, and watch classic old movies with Bette Davis or Audrey Hepburn. I see Suddenly Last Summer this way, with Elizabeth Taylor; her character, Catherine, has been committed to Lion’s View State Asylum by her rich evil spider of an Aunt Violet, who pressures caring psychiatrist Dr. Cooper (Montgomery Clift) to perform surgery on her rambling, babbling, violent, and promiscuous niece.[2] Dr. Cooper is a lobotomy specialist, who calls the procedure “the sharp knife in the mind that kills the devil in the soul.” Aunt Violet says she wants the surgery to help her niece, but in truth she wants snipped out and away an unpleasant and scandalous memory of Catherine’s dead cousin, Violet’s son. The aunt wields absolute control over the family, using her power and money to convince Catherine’s feckless mother to sign the authorization for it, and this Ratched-like supremacy is unnerving to me; it’s clear that Catherine isn’t crazy, she’s difficult. She’s inconvenient. I feel a sense of personal, familial threat hovering in my own living room. That evening I take pains to do an extra good and industrious job on my homework. I tidy up my room. I offer to do chores.

I also watch The Snake Pit, with Olivia de Havilland as another going-crazy woman, this time committed by her caring husband to Juniper Hill State Mental Hospital after she’s exhibited uncomfortably odd behavior: blankness, confusion, inexplicable hostility.[3] There is a nasty montage of hospital-gowned Olivia undergoing shock treatments – menacing shiny black machine, padded tongs, conductive gel scooped from what looks like a pot of marmalade – but the zapping itself is offscreen, save for the moans. Then, as more punishment, Olivia is immediately thrust into a ward with the craziest of the crazies. She stands in the throng of ranting and raving women, the camera swoops up, fast, and the ward visually transforms into a huge craggy pit, Olivia lost in the swarm. We next see her, now calm, polite, and well on her way to recovery, telling her caring doctor what she remembers reading once about “the snake pit” – how, in the past, they threw insane people into a pit of snakes in the hope of shocking them back to normality. Because, the theory goes, what might drive a normal person insane might well drive an insane person normal.

I still have Crazy Jack in my mind, but Olivia and Catherine become my images of Crazy Women, and they unnerve me because of their helplessness. There is an aunt or a husband in full charge of them; one is vindictive and one is loving, but both have the power to hand a family member over to someone with the even greater power to strap them down, use a sharp knife to kill the devil in their souls – or just an awkward bit of memory – or toss them into a pit of snakes.

Forget it, I tell myself, they’re just a couple of old, outdated movies. I empty the dishwasher, I Windex the glass coffee table in the living room, I bury my nose in whatever I’m supposed to be studying, no resentful attitude against work, no laziness, no bad behavior here.

Watching Frances in 1982, when I am eighteen, I spend much of the first half of the movie amazed the lead actress is the same insipid girl from the Jeff Bridges King Kong.[4] This time Jessica Lange is 1930s movie star Frances Farmer, who goes to Hollywood, refuses to conform, leaves after she can’t get along with anybody, and from that point it’s pretty much a sad downhill, as the ruling figure in her life, her mother Lillian, keeps terming her ornery willfulness as mental illness and commits her to a series of progressively-worse insane asylums.

The movie initially tries, I think, to make the point that strong, passionate women get punished, but what, exactly, Frances is so strong or passionate about isn’t especially clear. She does a lot of shrieking, and it seems unprovoked. But once she’s in the hands of people with power, once she’s placed in that very first “convalescent home,” the shrieking becomes rooted, substantial. It finally makes sense. As the movie goes on, shrieking becomes all she can do, all she has left – until the end, when even the power of outburst and outrage is taken from her.

I see the movie with my mother. Early on, Lillian Farmer applauds her teenage daughter for winning an essay contest, clearly a vicarious thrill for her, and my mother and I both feel warm and happy and identifying at that; I am a high-achieving, well-adjusted teen – a role at which I excel – and she is my biggest, most voluble fan. But when the movie shifts, when Frances starts acting out and her mother’s devoted and concerned maternal signature on papers becomes a warrant, a weapon, a threat, my old discomfort returns, increases.

Lillian sends Frances to Meadowbrook Hospital for some rest – but we hear the real reason from the Man in Charge: that with her feelings of “anxiety, hostility, guilt,” in her “present excited state,” her “mother is unable to control her.” Frances begs her mother not to do this, tells her she’s finally figured out the why of her messy life: the actress biz doesn’t work for her, she plans to buy a country house and have a vegetable garden instead: “I’ve realized the only responsibility I have is to myself.” She isn’t going to be a movie star again, but that flips Mother out – “You selfish, selfish child!” – and Frances dooms herself when she commits the ultimate sin; she tells her Mother — she shrieks it, in fact – that she doesn’t love her. That’s it.

Cut to Frances dragged shrieking, shrieking, shrieking, down a hallway in a straightjacket, to a syringe plunged into her thigh like a meat thermometer into a roast, and a rubber guard thrust in her mouth, to a procedure room, where a White-Coated doctor describes the beauty of what happens when a slender instrument is slid up under a person’s eyelid to sever the nerves of the temporal lobe, the nerves that “deliver emotional energy to ideas.” Electroshock first, to sedate the patient, helps, of course. That way, you can do ten an hour. Frances, bruised and covered with sores, is wheeled in, strapped to a gurney, while the White-Coated Doctor caresses something like an ice pick and holds up a hammer the shape of a small mallet, and, just out of frame, thank God, thank God, positions the pick, takes aim, and there’s a gentle but definitive tap. End shrieking. Cut to black, then the final shell of Frances, years later, autopiloting her way through a 1958 episode of This Is Your Life, then zombie-ing off alone down a dark Hollywood street.

Feelings of anxiety, hostility, guilt, a daughter blurting out I don’t love you and a mother’s accusatory You selfish, selfish child! —is that really all it takes?

I’m excessively sweet to my mother for the rest of the day.

My first therapist, when I was around fifteen, was a lovely man in sweaters named Steve, with an unthreatening office in velours and earth tones and macramé’d hanging plants. I saw him once a week and I remember he insisted I pay $15 toward each session – my mother was paying the rest – in order for me to feel more responsible and involved in my own treatment.

Treatment for what? Many of my friends went to therapists, and most of our parents certainly had. It was the late 1970s, it was Marriage Encounter and EST, it was the San Fernando Valley. It was an expected coming-of-age ritual, like nose jobs, a status symbol, even, a casual qualification for club membership. Annie Hall, an Unmarried Woman, and Ordinary People all went to shrinks. My parents had divorced a few years earlier, but that was expected, too, and, in comparison with other parents’ divorces – in comparison with other parents’ marriages, even – it seemed relatively bumpless, untraumatic, everything done by the book. I was by the book as well, a good kid, trouble-free and achieving, good grades, good friends, never cause for worry, a sweet-natured, self-reliant daughter who had learned to make zero demands on the self-absorbed, physically- and emotionally-absent father, who the divorce-traumatized, needy mess of a mother could lean on, depend on, the one who didn’t need any taking care of herself, no problem at all, a good good girl, a fucking Good Girl.

My mother behaved as if my visits to a shrink were perfectly ordinary, like going for a haircut – and yet, paradoxically, she seemed bewildered by it, taken aback that her perfect daughter was showing any kind of crack. I had asked, tentatively, vaguely, not wanting to alarm or disturb, if I could “talk to someone”; there was something hot and coiling inside of me, a simmer that terrified me with its threat of mess, like tomato sauce in a pot on the stove, little bubbles exploding to spatter the range with orange grease. There was no room in the house for my mess. I remember, at the first visit, numbly asking Therapist Steve if he wanted to hear my dreams. He said sure, because the process of discussing them could open stuff up. I don’t remember what they opened up, but I know I started to cry, loudly, and then I tried to stop crying, because crying leads to wailing and wailing leads to shrieking, and if I began to shriek and explode that way, I thought I might not be able to stop. It isn’t good to be a shrieking Afternoon Movie woman; people who say they care will do anything to get you to stop. And who knows what else might blurt out of you, along with the shrieks?

But everything was fine, really, perfect, I kept insisting in between choked sobs, so what was there to sit on a brown velour couch and complain of, what was there to cry or shriek about? I was ashamed of my distress, aware of my privileged life – what was I making such a spattery fuss for? Why be anxious, hostile, guilty? Therapist Steve seemed so nice, caring, but you never know; I apologized and smiled a lot, trying to assert myself as unanxious and already meek. But for fifty minutes, once a week: an explosion of choking, convulsive sobs without reason or source, of gasping for air.

I stopped seeing Therapist Steve not long after I started driving. My indulgent grandfather bought me a car for my sixteenth birthday and I was abruptly empowered; you can drive yourself places, escape to and away from, you’re an adult, autonomous, and it worked on me, somehow, that new ability to navigate the Ventura Freeway meant the magical ability to control myself and my destiny, even just a few miles of it. In the confined safe space of a Honda Civic, I could breathe. I was incredibly relieved; no more encroaching threat of orderlies in white shirts or shiny black machines, no more inexplicable crying, not for me.

“You know, your Aunt Edith was in a mental institution,” my mother told me as we drove home from Frances. I hadn’t known that, but now it made an awful kind of sense. Edith had died of cancer by then, a year or two earlier, and my mother told me about all the commitments – how Edith would go too far, go too nuts, my grandfather would say they had no choice, my grandmother would protest, but my grandfather would sign the papers and off Edith would go, to Unit 45 at Camarillo State Mental Hospital. Afterward she’d tell my mother about the electroshock treatments, how she hated and feared them.

“They shuddered her,” my mother said. “But your grandfather said it helped. It calmed her down. She’d go home and everything would be fine for a while. She would just be…normal depressed, not crazy. She wouldn’t be a problem for anybody. Then it started up again. And she’d beg your grandparents not to send her back there.” Pause. “But your grandfather said it was the right thing to do. It was for her own safety. And it was his decision. And she was never a problem after that.”

When Frances is wheeled off to her first round of electroshock we see the ceiling from her point of view, the stained tiles running past overhead, and I tried to imagine my Aunt Edith being wheeled off in the blind dark; she wouldn’t have known where she was headed, the first time, she wouldn’t have seen the menacing black machine. But she would have felt the cold gel on her temples, gagged on the rubber forced in her mouth, suffered everyone holding her down. I wonder if she shrieked, the second time they came for her. Or the next time she found out my grandfather had signed those papers again and found herself on her way back to Camarillo, or the third, the fourth. I have this version of her in my mind now, shrieking, locked away with Frances and Catherine and Olivia and wondering what hideous thing she has done to deserve such a punishment as this.

Because this is the real terror of Frances, The Snake Pit, and Suddenly Last Summer, the chilling thing beyond the electroshock and the ice pick and that conclusive, tender tap: that familial signature on the commitment form. There is a thin, shaky line between being crazy and being inconvenient, and this is the penetrating moral of these stories: keep on being a Good Girl, don’t piss people off. Don’t go too crazy, don’t say the wrong thing, don’t become a problem, a mess, don’t start shrieking, don’t lose control. Be sweet to your mother; be nice to your father. Look what a caring family member is capable of.

I thought about all of this again a few years later, when my grandfather, whom I adored and still do, and who was a man of impressively-catalogued lifelong angers and resentments, had disowned my mother, who also adored him, ostensibly for a single wrong thing she’d said to him one night at dinner, a careless and inappropriately disrespectful remark that got blurted out and triggered an enragement. But I believe it was my aging, lonely grandfather’s last bid at a vindictive kind of control, his wielding of a bolstering power against the only vulnerable person he had left: it was a Ratched-esque, Aunt Violet-like, Lillian Farmer-style bid for authoritative command. He was unable to control my emotionally extravagant and exhausting mother, and at the same time he resented her childlike dependence on him – he couldn’t cut out part of her brain, but he could cut her out of his life. He refused to ever speak to her again, and he died that way. It was an agony for her, a shock to her system she never fully recovered from; it kept her in an emotional straightjacket, made her a little crazy, and a little terrified of the people who loved her. And I’ll always believe he wanted to drive my mother a little crazy because he cared about her enormously; otherwise, that act of commitment would have been meaningless.

The story of my Aunt Edith is interwoven with the story of my mother and her father, a story of power, of control and self-control and the loss of those things, a story of the agonies a person who cares can inflict. But I’ll never know my aunt’s real story, or at least her version of the real story, because all those pages she wrote, what I think of now as a written shriek, a brave and futile attempt at going on record, have disappeared forever.

[1] One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest (United Artists,1975): screenplay by Lawrence Hauben and Bo Goldman, based on the novel by Ken Kesey and the play by Dale Wasserman; directed by Milos Forman; with Jack Nicholson and Louise Fletcher

[2] Suddenly Last Summer (Columbia Pictures, 1959): screenplay by Gore Vidal, adapted from the play by Tennessee Williams; directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, with Elizabeth Taylor, Katharine Hepburn, and Montgomery Clift

[3] The Snake Pit (20th Century Fox, 1948): screenplay by Frank Partos and Millen Brand; directed by Anatole Litvak; with Olivia deHavilland

[4] Frances (Universal, 1982): screenplay by Eric Bergren, Christopher DeVore, and Nicholas Kazan; directed by Graeme Clifford; with Jessica Lange, Kim Stanley, and Sam Shepard

Wow!!! Thank you for your story.

Thank you so much, Barbara!

[…] “How To Go Crazy: Electroshock, Beautiful Minds, and That Nasty Pit of Snakes.” (Tara Ison, February 2015, The Manifest-Station) […]

this is the most powerful, gripping piece i have ever read! what an amazing talent you are, tara ison, i’m so glad i’ll get to read more. xx’s

Thank you so much, Cecilia, I appreciate it!