Small bodies stared out a car window, helpless, listening to the drone of a voice, pitiless, and naïve, a horrible combination. Houses never furnished. Refrigerators full of liquor and doggie bags, steak slices, and baked Alaska, toddlers hidden behind beige drapes peeing on white carpet. Babies crying. Shit stains and Martini olives. Poodle yelps. Flash of ocean daylight. And remorse.

My Moody Sister died in a drug-induced coma. Dark hair matted with vomit. Fell asleep on a double bed in a Tulsa motel room beside her abusive boyfriend, and never woke up.

I jumped out of sleep to answer the phone.

“I’m calling to let you know,” my paternal aunt said. “Didn’t want you to hear it from none of them.”

Receiver to chest, I crouched down. Balanced on my heels, and rocked.

“Cancer,” my aunt said. “Had to have been. Just look at her obituary picture. Looks like it to me, like she died of cancer.”

I knew that wasn’t true. Got off the phone quick as I could and searched online for my sister’s obituary, head full of unanswerable questions. When did the drugs and drinking start? Was it because we had no real home? Why did she stay in Mama’s dark orbit so long past youth? Was it the only life she knew, or the only life she could imagine? Frantic and doubting, I searched until there she was in glowing bits, my Moody Sister.

Pixilated otherworldly eyes smiled above a brief paragraph.

She left behind three children, at least eight half siblings and survived by both her parents, was buried in an Ozark cemetery facing old Route 66. Her three children went to live with her last husband. Their names in her obituary were long jingly strings of karmic payback and wishful thinking: combinations of our Mama’s real first name alongside my sister’s absent father’s surname.

She didn’t meet her biological father until she was a grown woman.

Come from a childhood with no fixed address.

Identity, a combination of what you’ve done, what’s been done to you, flawed mosaic of who you are, and who others think you are. Not who you are inherently, but also who and where you came from, and what you were able to make of yourself.

Outcomes.

Origins.

Consequence.

She was Mama’s favorite child and most constant companion, always riding beside her in the front seat of the car as we traveled from town to town. Disregarding its isolation, she accepted the position of best loved, her dark head barely visible to the other kids crammed together in the backseat. When left behind with the rest of us she became inconsolable, running after the car, plopping herself on the sidewalk as Mama sped off. Sat there, cross-legged, head thrown back, mouth wide open and skyward, wailing with all her need, outdoors and out loud, for her Mama to come back home. My peaceful respite, lolling alone on the motel carpet unobserved with a new Nancy Drew, was her full-bodied pain.

The daughter in the front seat never learned to be alone; disconnection terrified her.

I ran away from all my family, especially my Moody Sister, putting real distance between us, and seldom looking back. Her unhappiness was of another order altogether from mine: unquenchable, indulgent, and seductively unhealthy, like too much syrup on an already too sweet dessert.

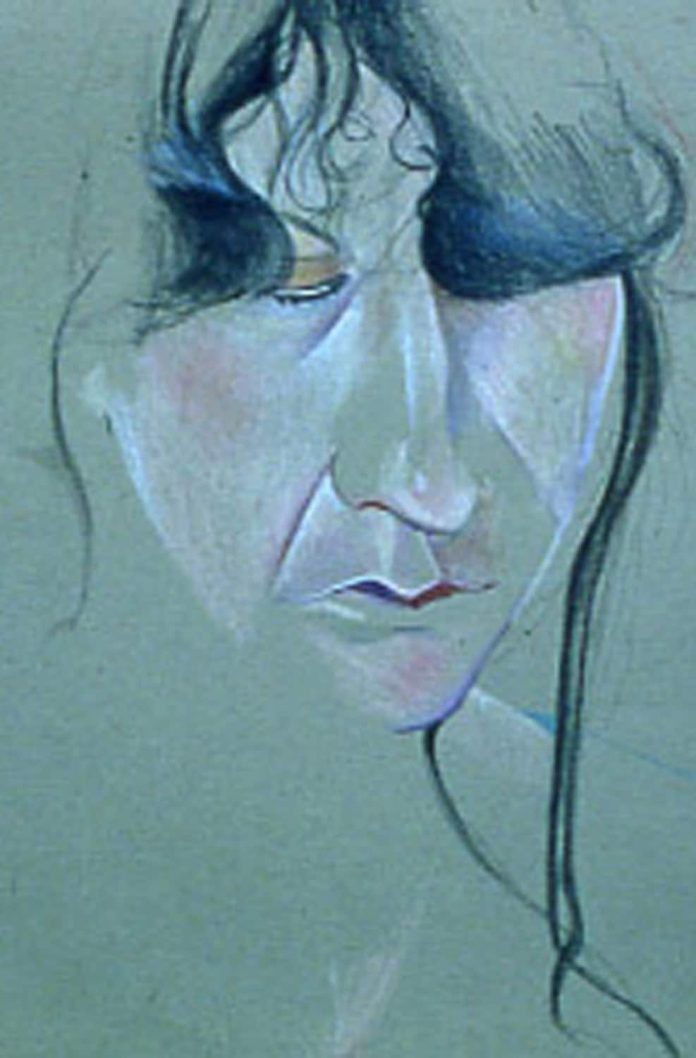

The last time I saw her, I drew her portrait. Pencils sharpened, I layered colored lines on a flat green page, porous and textured. Watched her bow her head slightly to the left, as she had done so often in our earliest days together, and recorded what I saw and what I knew to be true. Made art of our brutal detachment.

Long black bangs curled across a forehead into downcast blue eyes.

A heart-shaped face held sharp lips painted red.

Absence charged by a presence, deceptive and confounding.

Negative space I knew all about it by then. Had learned to carve a figure out of a flat plane, alive and pulsing. See the spaces between truly enough and you don’t really even need to fill in the blanks.

A kindred sufferer, my sister read her poetry aloud as she posed, extolling commitment phobia, wine and Mama.

At twenty-seven she was still living with Mama.

At thirty I was someone I’d hoped I’d never be: a divorced mom, living with her boyfriend, sharing custody of her son with her ex-husband.

Both of us were lonely, so very lonely, and wary, distrusting connection.

I should never have had any you. Any of you.

“Don’t you want to mute that voice?” I asked my sister. “Don’t you want to stifle the life out it?” I grilled her, sanctimonious and proud, and afraid of falling backwards.

In love with ideas—shape or blueprint for a craftsman—and reason—ratio to calculate—I loved rules. Wanted to know the rules and wanted to avoid their application. Couldn’t bear to be wrong. Thought I would die if I were judged wrong. Right away, wrong meant Mama to me. Wrong personified. So I hid away. Kept any confusion to myself. Didn’t ask for consolation. Became an egghead: disembodied and isolated, righteous and ready to save.

“Stay here with me and go back to school,” I said. Thinking school might be my sister’s answer because school had been mine.

I’d attended seventeen from kindergarten to high school graduation.

Most of Mama’s nine children had quit. Several of the youngest never even went. A few got their GED’s. Two of us graduated college. I was one. Had foster parents to thank for that. The caption under my graduation picture read: Christy Edwards, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas E. Doyle.

Next Year’s Plans: to attend Oklahoma Christian College.

That’s how I got to Edmond, Oklahoma where I met an older guy, married him and became a mother myself at twenty-three. Married and divorced by twenty-seven. I took my husband’s last name when I married, and kept it even after the divorce. Changed my name from Edwards to Embree, and from Christy to Chris. “Christy, sounds like a cotton picker’s name,” my husband informed me. “I’m going to call you Chris.” Why not? Born Smith. Adopted at three by Mama’s new husband Edwards, names meant nothing to me. I’d lost connection to a name long ago, when my biological father left and kept on leaving, when my adopted stepfather rescued his biological child and left the rest of us behind.

Five of my nine siblings grew into adulthood with that stepfather’s last name. My Moody Sister lived most of her adult life with that last name. One of my sisters still goes by that last name though Edwards was definitely not her father’s last name.

Identity. What is it really? Who and where you came from, or who you believe yourself to be?

A week into my sister’s visit I took to staying up with her at night. Watching her not drink when I was witness, not speak and not react as I made my case against Mama.

“Think about it,” I said. “Did she ever even read to us? Buy a children’s book or get one from the library and share it at bedtime. Ever once put us to bed with a story not her own? What about that? Don’t you get it? We were screwed—am I right? Answer me.”

“She was a rose,” Mama’s favorite finally said. “A beautiful rose.”

“ROSE!” I yelled. Imagining Mama as a fragile bloom to be held in reverence and awe as fantastic to me as any science fiction plot. I wanted to snap the word out from the already thick air, and toss it aside. Stood up, done with convincing, and more than ready to go to bed.

“You’re a trip,” my Moody Sister said. “You want to know what went down after you left? It got wicked. You think it was bad when you were with us? You don’t know bad. You had it easy. You got away. So you don’t know the half of it. She changed routes. Stopped driving west and turned east. We didn’t go to school at all. We went to the mall. Day after day we walked those halls. Wore the best clothes because we took them. Got the littlest ones to do it for us. They’re so fast no one can catch them. We stuck together,” she said. “I looked out for them. Not you. I didn’t leave like you did. They love me. Not you.”

That night I had trouble falling to sleep. After I did I saw things, thrashed fitfully, and woke up the next morning in pain. A band of hurt from armpit to armpit, neck to navel. A flame around my heart so constant and severe I could barely stand. When I did it was only with the help of my bewildered boyfriend, who immediately took me to the nearest emergency clinic.

Breathing with difficulty I stumbled in, broken in half and wondering what this might be.

“Pleurisy,” the doctor said. The pleura lining my chest cavity and surrounding my lungs were inflamed. “From friction,” was the way he described it. Membranes rubbing inside my chest like sandpaper.

What was once smooth become rough.

“Morphine is sometimes needed,” he said. “But there’s a lesser narcotic that would serve just as well.” He handed me two prescriptions, one for codeine and the other for infection.

My boyfriend had to get to work, so he asked me to drop him off and drive to the pharmacy alone. On my way there, in so much pain I couldn’t think straight, I stopped by our place to pick up my sister.

All that week I had searched for a way in, a way to say to her: there is another kind of world, sister. Better than the one we’ve known. A place with beach walkways, nutty muffins, incense, and cheap socks, gardens with thorny blooms, miniature trees, and serene spaces good for what ails us. A world with delicious food to eat cooked and served by handsome men, new neighborhoods to walk through and interesting streets to amble down. Waiting in the pharmacy I still wanted to say all those things to her, but I didn’t. I couldn’t. I no longer had the breath.

“If you want to stay you can,” I whispered. “We could even get a dog.” Why not? My son wanted a dog. And my sister loved animals more than people, so I offered up the possibility of a pet. “Would you like to stay?” I asked. With each exhale and inhale, wincing in pain, waiting on relief and on an answer. From someone I had known from the beginning of knowing.

“Give it to me,” she said.

“What?”

“When you get that prescription I want you to give it to me.”

One night in the back of a van, after swallowing a handful of Darvon and Percocet, on the edge of consciousness, chest pounding, eyes fluttering, and at the mercy of acquaintances, she’d almost died of a heart attack.

At least that’s how she had described it to me.

“If you are really sick,” I told her, “I’ll take you to a doctor so you can get some help. If not you need to go.”

She laughed. “When we were little I wanted to follow you when you went off into that other world of yours, away from Mama. But you would always shake me off. Trying to fit in and look normal. Look at you. You still are. Anyway,” she said. “Maybe I did you a favor. Maybe I made you run a little faster.”

“Say you’ll stay. Say you will. Please. I mean it.”

“It is what it is,” she answered.

That night my boyfriend took her back to Tulsa, back to Mama.

I sighed with relief as they drove off, unaware it would be the last time I’d see my sister in this lifetime, the dark-haired one just three years younger, who was bigger and taller and always in a mood.

Eighteen years later she was dead at the age of forty-five.

Mama gone too, and I still couldn’t get that voice out of my head.

You’re a mess you know that? Not the kind of girl that does well. Just not pretty enough. I have a use for you, so I will keep you, but I don’t want you. Nobody does.

For months after my sister died I studied a photograph of us, the first three kids in Mama’s car—the original three. A studio shot taken on Easter when I was seven, my Moody Sister was four, and our baby brother was two. The print was old and somewhat discolored: an Easter egg yellow. The children depicted looked well cared for, well dressed and happy. I remembered the feelings I had the day the photo was taken: a mix of kid craving for the good stuff combined with a knowing dread of Mama’s post holiday letdown.

Christmas and Easter were the ones she worked herself into a perfection frenzy over, making sure to get all the right stuff: baskets, chicks, new outfits—all the props. It must have been Easter when the photo was taken because we were all three really decked out. My brown hair curled in ringlets, my brother in a spiffy two-piece outfit and my sister with a hat on, a big bow tied under her chubby chin. The sleeves of her dress pressed in on her little girl forearms, her blue-black hair so very long.

I looked at that picture, haunted, still in the backseat of the car with my siblings listening to them cry for what Mama didn’t know how to give, always afraid she was growing another one, another child I could only mother as best I could.

Please, please not another baby in the backseat, sleeping unawares.

When I got the call my sister had died I didn’t try to contact any of my family. Instead I stared at her online obituary, ruminating on wrong turns.

And disconnections.

What made my sister my sister besides a shared mother?

My sister was tall. I am short. Even as a kid my sister was melancholic. I was athletic. Running when she stayed. Leaving while she remained in the comfort of darkness.

“You can have boys over anytime you like. You don’t even have to go back to school if you don’t want to.”

The things Mama said to keep me were not what I needed to hear.

And not what I wanted at all.

Saved by people who stepped up when blood kin couldn’t.

In foster care I had periods of panic and shortness of breath. For a while I slept with the help of pills. Played hooky from school to listen to sentimental show tunes sung by middle-aged men. Cried all the truant days away alone and ashamed.

Until torn to pieces I found another way to make myself whole.

I read poetry and plays and stories. Wrote and drew. Painted female bodies in monochrome, fractured and fragmented. Blown apart. Drew faces defiant and boxed in, eyes flat and fixed.

I held on to art. Not anger or hurt, letters, lines, the color of words and ideas.

I built a self with them, someone beyond and more than the sum of my parts.

Self-made means craft, craft of snot and hurt and hope. Guts. Stuck together semblance of whole.

Gestalt.

Humanity.

The very idea of humanity sustained me. Kept me from breathing too fast. Trembling for fear of closed in spaces. The pain baked into my brain whorls soothed by the balm of art and books: The Bluest Eye, The Woman Warrior, The Golden Notebook, and David Copperfield. Dickens, Morrison, Hong Kingston and Lessing. Orphans and refugees, runaways and outcasts, kept me moving, inward and upward, into my body, a body of knowledge.

Identity. Not only who and where you came from.

What you were able to make of yourself as a consequence.

The day I got the call my sister had died I dressed for my new job: slide librarian at an art and design college. A job I had wanted and worked hard to get. Even earned another degree. A second masters degree. Now all that effort meant nothing. When my new boss asked me what was wrong, I answered: “My sister died.” Didn’t explain. Didn’t elaborate. Continued checking out slides and videos, organizing documents, archiving and filing and keeping safe the works of others.

Made their thoughts and feelings accessible. Not my own.

After work I drove straight to the grocery store and bought a steak. At home I barely cooked it. Ate it bloody raw, then put my head on the clothes dryer and cried. Warm and vibrating and alone, in a place where no one could see me. No one could hear me.

Went to bed early.

Woke up the next morning and couldn’t turn my head to the right.

Frozen by invisible grief.

Come on, sister; say it with me. If I should die before I wake. Now I lay me down to sleep. I pray the lord my soul to keep.

K-E-E-P.

I wrote that word in the air with my finger, spelled it out in the world, wishing like mad to repair my fractured family.

Sisters.

Part of me was related to a part of her. Now she was dead, and I was diminished. Broken in half, moody as my dead sister, and living as if in a fairy tale, awaiting the next revelation.

Disenchanted.

Banished.

And longing for transformation.

Chris Rice is a Missouri born artist/writer settled in Los Angeles, after earning an MFA from the California Institute of the Arts. Her writing has more recently appeared in Necessary Fiction and [PANK] Online. Her twitter handle is @leapof, as in leaf of faith. Chris recently attended “Writing the Body,” a workshop co-led by Jennifer Pastiloff and Lidia Yuknavitch. Featured image by Chris Rice.

To get into your words and stories? Join Jen Pastiloff and best-selling author Lidia Yuknavitch over Labor Day weekend 2015 for their 2nd Writing & The Body Retreat in Ojai, California following their last one, which sold out in 48 hours. You do NOT have to be a writer or a yogi.

“So I’ve finally figured out how to describe Jen Pastiloff’s Writing and the Body yoga retreat with Lidia Yuknavitch. It’s story-letting, like blood-letting but more medically accurate: Bleed out the stories that hold you down, get held in the telling by a roomful of amazing women whose stories gut you, guide you. Move them through your body with poses, music, Jen’s booming voice, Lidia’s literary I’m-not-sorry. Write renewed, truthful. Float-stumble home. Keep writing.” ~ Pema Rocker, attendee of Writing & The Body Feb 2015

Stunning. Incredible. Wow.

Amazing. Raw.

I could picture it all in my head & feel the emotion heavy in my chest.

This is an incredibly rich piece of writing Chris. Thank you.

nancy

That was amazing, I felt like i was there. I literally have pain/hurt in my heart right now. I don’t have the words to describe how amazing that was. Wow