Black Lace: On Music, Motherhood, and Loss

By Geri Lipschultz

Nothing is sexier than black lace, nothing more deadly. When it’s cut in a circular shape, one slips the bobby pin inside, fixing it there into your hair. With the black lace thus covering, you can show respect upon entering a synagogue or a funeral parlor where your mother is, before she will be buried. It may only be nine months after your father died that she developed the cancer, less than three months before it would kill her—and in between that time, that is, in between the two deaths, you, at forty-six, would deliver a girlchild in darkening November. With the lace in your hair, you are holding the girlchild in your arms.

My daughter’s love for me was palpable. A friend had seen her spirit when the baby was in utero. Her shade was long, Tibetan, a tall thin dark man who sat on my shoulders and wrapped his legs around me, put his head upon my head. Cradled me. Farfetched or not, this was the feeling of this baby. Loving, attached, but withdrawn among strangers, whereas my son would work to catch the stranger’s eye. Born eleven years before, my son had colic. I held him, and he cried. Even his entrance into the world came with a face of doubt, a scowl of woe. He was covered in meconium, an expression of his discontent? My daughter swam into life, looked up, surveyed it, said it was good. Did my daughter know she was conceived in wedlock?

I was already married a year when I found out I was actually pregnant, for the second time, at forty-six, and I called my mother to tell her this. She expressed something that sounded like horror. I asked her if she was horrified, and she said that she was worried. I was too old. She was in her seventies. The other grandchildren, my sisters’ kids, were teenagers, mainly. My son, David, was ten. He would be eleven when Eliza was born. I told my mother to please keep her horror to herself. I told her I was thrilled, that she should pray for a healthy baby, preferably a girl, for me, and if she was worried, to please not inflict it on me. It vaguely reminded me of my writing, the once or twice I’d shown her what I’d written, her inability to take it in, her tendency to read too much into the stories. I wrote stories, fiction. The lace of words, of black on white, the way stories gush up into images. You turn something terrible into something beautiful. I made things up. If it was good I made it bad—some bit of salt or pepper or honey to change the flavor. If I told the truth, I would feel guilt, but the truth can hide behind a lie. It can light up the sky. For a long time after my mother died, I felt the guilt of someone who did not do enough because she could not cope, could not take in the loss. I was in the thick of motherhood, myself.

Black lace is what’s left when the mother is gone. A string of memories, a household full of items, tangible and laden and one day all of her furniture and even her wastebaskets would be sent to your house, because you were the one without a real job, just adjunct teaching and the pittance you made from your writing. Not to mention the insecurity of your marriage. Sometimes, if you could, you would take a match to the world. Sometimes it felt as if someone had. Can you admit the waters of grief? Stunned, after your mother’s death, you walked away brittle, unfeeling, protective, pretending. This has become your way with any kind of loss, until music arrives with its stream of the eternal, its messages, its images, its notes and rests and etchings.

Married or not, I approached motherhood with the vengeance of someone who felt she had to do something right in her life. I’d heard about the Suzuki method, that you could start a child quite young. As a child, I, too, had perfect pitch. I used to sing songs with my father, with the radio. I’d mutilate the words, such that “the back fence gossip,” from “The Naughty Lady of Shady Lane,” became “the bask fen gospay.” I had no idea what I was singing, but I sang. As a toddler, I’d be dressed for bed but stay up to hear the Dinah Shore show and part of the Perry Como show. I begged for a piano, and my grandmother bought me an old upright for twenty dollars when I was seven. I took lessons for ten years. I played Beethoven, Mozart, Chopin. More important than that, I played my heart out. When I was happy, when I was angry, when I was bored, I played. In college, when everyone else was doing drugs or transcendental meditation, I’d be scouting out pianos. It was my dependable attitude shifter. It charged my brain waves into something that resembled meditation. It turned the bile back into blood. I knew what music could be for someone.

There is something about passing on what is given to you, the feeling you cannot let it go.

That is what happened when my son was born, when he displayed the sign, which was when he was less than two years old, when a humming happened. The recognition was not immediate but came upon me gradually, during our car rides, as the music was playing, gratis of the cheap classical cassettes I’d gathered for my incessant traveling. As challenging as it is for a driver to pick up back-seat conversations, it’s infinitely more difficult to decipher a child’s murmurings, especially over the music. It was when the music stopped, when I heard the humming, when it occurred to me that what he, my son David, was humming was Beethoven, the seventh symphony, to be exact. I drove a lot in those days, back and forth, from my boyfriend’s, Erwin’s, mother’s semi-attached house in Brooklyn, to the house of my girlfriend, on whose property in Long Island I’d lived before my baby was born, where we—the baby and I—had stayed for as long as we could. It was a remodeled chicken coop. We stayed there until winter came in hard, around December, when the kerosene heater had to be brought in.

Once I played music, and now I listen to it. But the listening is informed by the one whose body transfused itself in the act of pressing piano keys. In the struggle of constructing identity, for me it once was a gem of my being that I unwittingly projected myself into the world. One recognizes such things, what it is people single out about you. Now, for me, it’s about how I write or how I say things, how I see the world. Initially, for me, they were my eyes, everybody would stop me, talk about green eyes, beauty, and then it was the piano, how I played, how I should go to Juilliard, how I should practice. This became especially intense when I was about sixteen, in love with a football player, to whom my heart, body, and soul felt magnetized. About that time, an immensely gifted violinist befriended our family, and I would play the piano for him, and he would advise me. Without a doubt, I loved the piano, but I did not cherish practicing, did not foresee my life in a practice room with music I could only bear in my fingers but not in my ears. I let my music go. I would let this boy go, too. I would have no choice. And then he would reappear wrapped up in the lace of my dreams. Music and love, life and death. I loved him, my love haunted me, in dreams, in preoccupations, through my marriage and my children, and when my parents died, I left that haunting, set it aside.

Death separates us, but music joins us, brings it all back, removes all the differences, everything you’ve buried rises to the surface, and for that moment when listening happens, or if you are playing it, you are whole. People dance to music, people clap, move their fingers and toes, swing their shoulders; there’s a pounding inside where tears are marching in their canals; people who have forgotten their very names remember the words to songs they have sung. Engraved in our soggy brains music waits for us.

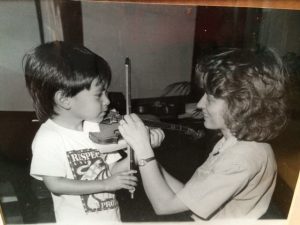

Here is where it began, where the music became a thing for me, the parent, rather than an idea for me, the dreamer. I watched as the child set his chin upon a tiny wooden table and then arched his back, relaxed his wrist, wrapped his fist, barely the size of a golf ball, around the gargoyle’s limb, his twiggy fingers grasping, curled, then padding down like the paws of a six week old kitten. His other fist was gnarled about the end of a magic wand. The child wasn’t much older than a kitten himself, and the gargoyle, too, was a baby, only a fraction of the size of its progenitor. No, not a gargoyle, but a violin. And the wand, diminutive as well. The teacher kneeling down before him prepared to reassemble any erring part. She resembled one of the archangels. It was more in the delicacy of her features, the indelible sweetness of her smile, the look in her eyes an amalgam of humor, determination, compassion; it was the nurturing that spun out of those eyes that were entirely focused on the child. The teacher, Thalia Greenhalgh. She would birth music in both my children. Her teacher was Louise Behrend, who would one day teach Eliza, my girl. This child was David. He was four years old.

A powerful backstory hides in a corner. The banquet depends upon what happens before the banquet, the shifting of the bowls, the measuring, the aprons, the morning light before a smell has arrived, the dream that coalesces into being. Each person, each family who comes to Suzuki, who comes with this plan to offer music to a child, has a story.

So, it happened that I gave David this choice when he was four years old, between piano and violin, and he chose the violin, and I found a violin teacher. I saw advertised on one of those roadside church signs: “Suzuki Violin.” That was twenty-five years ago, six teachers ago, probably as many violins ago, and now he is his own teacher, a musician—improvising music, who himself is a teacher. Eliza, too, fifteen years of music, now that she is seventeen, off to college for music. Six teachers, and nine violins. The violins growing with the child.

My son who came into this world to join two unmarried people. My daughter, born to seal this love eleven years later—the both of them finding their way on earth with a violin and a bow.

There was black lace like kudzu over the oxidized bridge in Central Park. We would drive underneath it, my daughter and I, on the way to her lesson. We’d cross the park, after we drove up Third Avenue and turned left on 65th Street. There was black lace rising up, falling down, the breath of Zephirus, fanning out, the buds deep in the sexual earth, the mothering earth tree holding on for dear life. The spirits of a million birds in the branches, swinging, tilting, my parents there, too. I am carrying a life with me wherever I go. I took my nine-year old daughter to her music lesson with a woman in her nineties of whom I was in awe.

Both my children willing to take in the rises and falls, the nuances, the sequences, the flights, the rigors, the demands of classical music upon a listener. I fidgeted at concerts. I could not sit still. Yet I loved the piano, my fingers felt like weavers of cloth, nimble instruments themselves, the ivory upon my fleshy fingertips, the balance of my body in a kind of communion with the large beast. I felt a feeling of mastery when I played, with the full range of the keyboard at my command. I suppose I was in high school when I was at my best, and this pursuit was soon overtaken by supercilious things like cheerleading and clothing and love. I would not major in music but I would never abandon it, and I always returned to it when the world let me down. I could self-console with it. I could return to myself. I could give it to my children.

There was a tranquil light that comes from the east, the refraction of the setting sun, filtering into Miss Behrend’s apartment. That light settled onto the off-white couches in her living room where the Steinway grandly waited, upon which were some opened frames, sketches of her beloved cats asleep in violin cases. In another room, she was teaching Eliza. I listened for the dialogue, as well as the music. Miss Behrend did not play but sang what must be heard. I was listening for voices. If I didn’t hear my daughter’s voice, I knew what to expect, but I, like the piano, waited. When the two of them came into the room with the piano, I knew it was time for the finishing touches of a piece, a performance coming close. It was also time for me to accompany, and I would do what I could; it would not be sufficient. I knew that day would come.

I think of that black lace I saw on the bridge, because of the light, the way the leaves and the vines and the bridge itself coalesced into lace. I knew my love for music, for my children, opened up this world of human beings who knew that life was about giving, was about making a contribution, was about staying power, was about stubborn love and discipline, and history. So I return to the image of lace because of the endlessness of the thought and the pronouncement of each word, the assurance of letters, of curls and flares and stitches and sparks, of note after note. Of leaves and trees and the arc of the bridge, and the way light adheres to each single visible cell, the way sound wraps its waves against my body, its darkness. There’s darkness and there’s the light that can come through, and the color, the leaves, the love and aching vines can come through. So when I think of Miss Behrend, I think of my daughter holding back large tears in her eyes, like a bubble on plastic stem, and I think of the look of a tiger about to pounce in Miss Behrend’s eyes, as she drives Eliza to play with more feeling, more bow. I see that trembling in Miss Behrend’s hands, as well. It calls to me a look of Bernstein coming through, that power embodied, that fire, in the face, in the eyes there is fire. I forgot she was ninety-one years old, and I forgot that she was a woman, or even mortal, and I was breathless watching, and of course, playing a terrible piano. So terrible she actually asked me not to play. And then I was just watching, grateful to be able to watch.

The elements gather to weave and rise and inevitably fall and I wonder how far into darkness is falling? One day I will leave my Eliza, my girl I can’t hug enough, can’t kiss sweetly enough. How I have refrained and stood back and simply watched. No longer her accompanist, nor his, my boy, on his own now. All I can offer them are my prayers. One day my death will be the best present I can give them.

Once upon a time you wrote words that were the notes of an unheard melody. The burden of history flowing in veins and vessels, a basket tied to the button of all birth, from your parents to your children, the lace looped around the grace of a flight that cannot be fixed, all of it singing there, singing into the night air.

Geri Lipschultz holds an MFA in fiction from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, as well as Ph.D. from Ohio University. She teached writing at Hunter College and Borough of Manhattan Community College. Her work has appeared in The Toast and 5X5, NonBinary Review, and in Helen Literary Journal as well as The New York Times, among others. She was awarded a Creative Artists in Public Service (CAPS) grant from New York State, and a story of hers won the fiction 2012 award from So to Speak: a feminist journal of language and art. Her one-woman show was produced in NYC by Woodie King, Jr. Geri is one of the bloggers at wewantedtobewriters.com.