By Tanya Slavin

Martin stands at the edge of a swimming pool, nervously shifting from one foot to the other, his whimpering becoming full blown crying the longer he stands there. I am waiting for him in the water, my arms invitingly outstretched, ready to help him in whenever he’s ready. I’m not pressuring him to go in, but the whole situation is: most of the other 4 year olds at this birthday party have been splashing happily in the water for a quite a while now, their happy babbling at stark contrast with his nervous wails. Some are already out of the water, getting ready to go upstairs to the birthday boy’s apartment for birthday cake and more fun.

Martin isn’t scared of the water. I take him to our local YMCA kids’ pool regularly where we splash and play happily. But the big difference is that the water in that familiar pool starts ankle deep, so he can move gradually, at his own pace, into deeper water, or stay at ankle depth if he chooses to. In this pool in our apartment building, the water starts waist-deep right away for someone his height. The other kids don’t care, but Martin isn’t comfortable plunging into that depth right away, so he stands there on the edge, scared and screaming.

I keep my hands outstretched and my voice positive and encouraging, when a sudden flashback obscures my cheerful attitude. In this recurrent nightmare of mine, I’m small and standing alone on the edge of a void that is formed by several missing steps in a stairway of my school building. Everybody else (all my classmates, teachers, my parents) have jumped over the void without giving it a second thought, and are happily on the other side, now encouraging me to jump over, their cheering voices ensuring me that it’s not that hard. But I am completely paralyzed by fear, and my knees begin to shake every time I try to make a step forward. I am certain that if I try to jump, I will fall into the void. So I’m standing there frozen and not jumping even though I desperately want to be on the other side with everybody else.

Alone, on the edge of the void, is where I spent my entire childhood. There was always ‘that side’ and ‘this side’, and a huge void in between. On that side were clowns and bouncy castles, noisy parties and dancing, being good at sports and being updated on the latest pop music, make up and girl nights out. ‘This side’ housed a comfy chair and a pile of books, being too sensitive and crying too much, and being scared of heights and elevators. It was understood and clearly confirmed to me by every trusted person in my life that ‘that side’ was the right one, and if you weren’t already there, you were expected to try hard to jump over.

And now, there was Martin, sensitive and cautious like me, only 4 years old, and already claiming his lonely post on the edge of his own void, alone. And I am the one who has jumped over, encouraging him to join me in a cheerful voice. We are just a few inches apart, but it suddenly feels like we are miles and miles away from each other and can barely hear each other’s voices.

By the time most other kids are already out of the pool, Martin finally agrees for me to hold him in my arms above the water, but every time I try to kneel so his feet touch the surface of the water, he screams on top of his lungs. He doesn’t want in, he doesn’t want out, and I am at loss at what to do, so I occupy myself with needless apologetic explanations to address the surprised looks of the few remaining parents in the pool that no, he’s not actually scared of the water, he’s just very cautious and sensitive, that’s all…

After this pool fiasco, I was determined not to take him near that pool for a long time, and not to make any water related encouragements near any other bodies of water. But to my surprise, just a few days after that party he suddenly asked to join me when I was going downstairs for a swim. I agreed, promising myself that I’m not going to have any agenda for him whatsoever, that I won’t try to persuade him to go in even in the subtlest of ways.

It’s easier said than done, letting go of the agenda. Especially if the child accidentally does step on the path that the parent secretly wishes them to go, it takes a lot of restraint not to jump in and try to lead the way, but to keep a curious and open mind, and to let the child lead. Fortunately, we were alone in the pool this time. We ‘raced’: me swimming, him running by the side of the pool. He didn’t seem stressed at all this time, even though I was in the water and he wasn’t.

I kept thinking about that little girl, the part of me that stayed alone on the edge of that void. What does she need? Does she really need to jump over like everybody encourages her? Not really. She just needs someone to stay with her on her side, always, whatever she decides to do. Someone to let her know that nothing is ‘wrong’ with her, that she just perceives things in a way most other people don’t, because we all see things differently. Someone to let her know that it’s ok not to jump, or to jump tomorrow, or go around and take a longer path, or simply go and have tea and biscuits on this side of the void. Because whatever you feel it’s right.

That’s what Martin needed too. No outstretched arms and happy faces cheering from the other side of the void. I didn’t offer him to go in. We played shark. He was sitting on the edge, and I was the shark, swimming towards his little feet, and “biting” them. He was squealing with delight. Then, unprompted, he asked to climb onto my back. Slowly, very slowly, we separated from the edge of the pool, me listening carefully to any tensions in his little body on my back. I’m not guiding. He is guiding. I don’t care that everybody else has jumped over, I’m staying with him whatever he decides to do. We moved an inch or two away from the edge of the pool and he asked me to put him back. I swam some more. Next time he climbed onto my back, he was able to stay there a little longer. We walked along the edge of the pool, his feet barely touching the surface of the water. He was holding onto the edge with one hand. Another break. During our next walk along the edge, he allowed me to bend my knees so that more of his feet were in the water. After a few more tries, we separated from the edge, and I was able to bend my knees more and more, until I was kneeling and Martin was standing on the floor of the pool. He kept holding on to my shoulders, and climbing back onto my back from time to time, but he was in the water now.

Minutes later – and he was splashing, and blowing bubbles, and asking me to support him on his belly so he could “swim”. It was hard to believe that this was the little boy who was hesitant to put his toe in the water just thirty minutes ago. The fear was gone completely. He was exhilarated with his success and so proud of himself. He was yelling “Mommy I love you! Mommy, I love swimming so much!” And I was so so proud of him. And it wasn’t even my goal to get him into the water, but simply to stay with him, whether it is in the water or on the edge of the pool dry.

Sometimes, we so badly want them to succeed, and have fun, and fit in, that we forget that the most important thing is for them to be themselves. We so desperately want them to jump over the void, that they often pretend that they do, to make the world look the way we want it to, but a small part of them stays there alone on the edge of the void, forgotten by all. This little big pool success showed me that magic can happen if I stay open minded and curious and compassionate, if I let him lead, if I decide that my most important role as a parent is to not to leave him alone on the edge of the void.

Tanya Slavin is a freelance writer and a recovering academic who was born in Russia, grew up in Israel and spent most of her adult life moving around North America and documenting a Native American language. She now lives in the UK with her husband and two kids. You can find her at Invisible to the eye and on Twitter @invisible2the.

Get ready to connect to your joy, manifest the life of your dreams, and tell the truth about who you are. This program is an excavation of the self, a deep and fun journey into questions such as: If I wasn’t afraid, what would I do? Who would I be if no one told me who I was?

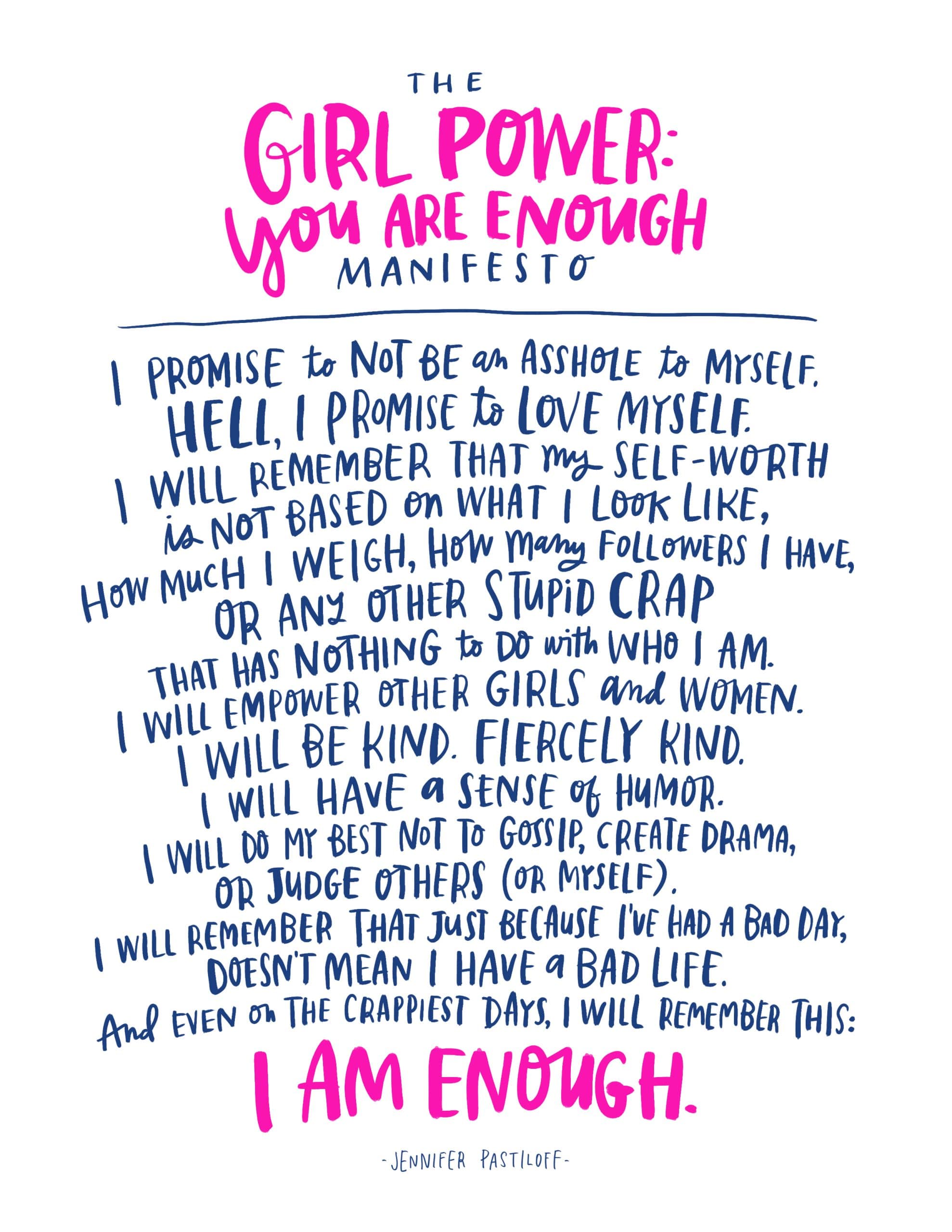

Jennifer Pastiloff, creator of Manifestation Yoga and author of the forthcoming Girl Power: You Are Enough, invites you beyond your comfort zone to explore what it means to be creative, human, and free—through writing, asana, and maybe a dance party or two! Jennifer’s focus is less on yoga postures and more on diving into life in all its unpredictable, messy beauty.

Note Bring a journal, an open heart, and a sense of humor. Click the photo to sign up.

Jen is also doing her signature Manifestation workshop in NY at Pure Yoga Saturday March 5th which you can sign up for here as well (click pic.)

[…] Read full essay on Manifest-Station […]

Wonderful story. I hope many parents read this.

This is a wonderful story of how compassionate being-with can have healing and strengthening effects on another person. It reminds me so much of Chogyam Trungpa’s school of therapy in Boulder, Colorado based on his style of Tibetan Buddhism. As a therapist for 37 years, I worked with some very disturbed persons who really needed me to be all there without expectations. Just with an open heart and mind. No expectations. In my last 4 years of work at a Mental Health clinic, most of my practice was with victims of abuse–sexual, physical, emotional and verbal. Many social work therapists did not want to do this because of the terrible feelings it brought up in them. Again, just compassionate being there without expectation and, always, an attitude of full safety would lead to the slow regaining of trust in a person’s self that had been so damaged by trauma.

You write a wonderful essay with deep meaning for parenting and helping others.

[…] She now lives in the UK with her husband and two kids. Her essays appeared on Brain, Child and Manifest-Station. Find her on her blog Invisible to the Eye and follow her […]

[…] Slavin is mother of two and a freelance writer. Her essays have been published in Brain, Child, Manifest-Station and Washington Post. Find her on her website, or follow her […]