By Coriel Gaffney

It’s a biting mid-December Saturday when I show up on your doorstep in a knee-length down coat and cheap pharmacy gloves, the threads worn through at the fingertips. Even from behind the closed door, I can hear the sink running in the kitchen and your dogs crashing into each other as they leap at your feet. I push the door open and you turn toward the sound, hair uncombed, shirt stained with coffee, to greet me with your usual gasp and kiss. My clockwork presence in your home every weekend does not diminish your surprise. I notice you are careful not to say my name.

In your arms is a bouquet of all the things you forgot to fill, replace and adorn, an homage to your morning, which falls to the hardwood floor in the excitement: a remote, the sink drain, a sweater, a leash. I pick them up and set them aside, filling your hands with the gifts I brought instead—mixed greens and DVDs. You examine each quizzically until the little dog yelps, startling us both.

I suggest we do yoga in the living room and you are game. But a few minutes in, you get stuck switching from cross-legged to all fours, and I have to wrack my brain for ways out: Come to Cat. Roll over your shins. Extend your legs. Lie back.

Once you are untangled, I grab our coats and we retreat to the front yard to shovel the walk. As I toss heaping mounds of snow backwards and overhead, stomaching spasms of effort, you follow me with a broom, sprinkling powder where I’ve just cleared a path. In my peripheral vision a neighbor saunters past; too curious, too slow.

The sun sinks in the blinding white sky and our busy shadows lengthen side by side. I watch the relentless clouding and dissolution of our labored breath and track the hour through traffic sounds: a school bus chugging up East Grand; a mufferless motorcycle tearing downhill. When it’s too cold to feel our toes, we head back to the house by way of the breadcrumb trail of snowdust you left behind.

In the bedroom I lift the sheet so you can slide underneath, still in your corduroys, wet at the ankle hems, and bring you a handful of pills. Aware that I’ve exhausted you and guilty that I wanted to, I hum you to sleep. But when a searing orange fills the windows, I squeeze my eyes and forget my song.

Once darkness descends, you are snoring and a new layer of snowfall starts covering the paths I cleared. Suddenly, it no longer matters which half-brain or full-brain picked which tool to occupy the minutes between storms.

——————-

Can’t this all be less painful? Less singular? Just part of a normal trajectory— we fade in, we fade out? Can’t they even be beautiful, these shortening days? Can’t it feel like abundance to watch your mother dance in her sleep, her legs cycling through a dream, her dogs turning in circles before plopping beside the scoop of her neck?

I write to document this catalogue of our time, which otherwise remains only with me.

——————-

When your own mom was old and sick, you used to joke, “Just shoot me,” like so many others have and will, “if I ever—.” You were 50. Well-versed in gallows humor.

Ten years later, the wisecracks were replaced with a heart-shattering sweetness as the plaque bloomed in your brain. Then drug trials, pills and more pills to address the side effects of pills, seizures, a heart attack. Then intubations, sedations, cartoonish oven mitts taped to your hands to protect the IVs. Then the moment when we elected not to do an angioplasty, which would likely prolong your life, and a serious cardiologist offered this: “Sometimes the best thing is to do no harm.”

Then “ever” came.

Now here we are, instructionless, as you expand like the universe before my eyes. And here is my grief, laid bare. I write to resurrect us both.

——————-

Four months before we had a name for the monster bent on destroying you (Early Onset Alzheimer’s) but well after stories started to seep through the holes in your head, I wore yellow sneakers and a sales rack dress—in a display of bridal ambivalence—to my wedding in your backyard on the highest summit of Fair Haven Heights. In spite of everything, I was happy and deeply in love with the partner I had chosen who stood tall in a yellow shirt (to match my footwear) and smiled ear to ear. He loved me back and did not want an uncomplicated life.

During the ceremony, you shared the poem you’d spent months writing. It began, “The child arrives protesting: she will be heard and you will hear her.” I read along with baited breath, trying to will your shaking hands still. From time to time, you recited different words than the ones swimming on the page. When I looked up, everyone was teary-eyed, but few knew the extent of your bravery.

——————-

People in my life– friends, co-workers, even strangers— want to know if you ate a lot of fast food. Some suggest a spiritual crisis. Others barrage me with a litany of questions. What meds was she on? Which vitamins did she take? How many concussions did she have? Did she test high for aluminum? How old is she? But isn’t that rare? Then, cautiously: Isn’t that hereditary though? I learn to recite stock answers. They are calculating their proximity. Trying to contain the damage by locating its inception. They want to believe in your culpability.

I hate how they resent their loving parents; that they flaunt their grandparents’ mobility. I hate their morbid curiosity; how they put me on a pedestal. I hate their smug green juices and how they plan their carefree weekends. I hate that they believe themselves exempt. I hate myself for hating them.

When we’re old, my sister and I promise each other, we will be magnanimous. For now, we settle for functioning.

——————-

A decade ago, in our past life, when we both had AOL accounts, you were a guidance counselor and I was broke, tired and 22, with spider veins webbing on my thighs. My body turned into a gaze I could not meet, and I took to undressing in the dark. Equally embarrassed by my mortality as by my vanity, I wrote you a despairing email. A few hours later, I received your reply:

Veins. Well have you ever looked at my legs? I realize I am decrepit and ancient, but I spent my life using my body. I have scars and bruises and veins all over me. I can see purple traces of every adventure and catastrophe I fell into…I think of my body as a map of what I have done with it. Stretch marks from my amazing adventures of motherhood. Scars from car doors and barbed wire and too much sun.

Scars and freckles and veins are not mars on our bodies but badges of our life. You are noticing that you are adult, reaching the part of life when your own body begins to testify to your presence on earth. You have had scars and veins since before you were born, and will keep earning them until you no longer breathe.

The blue veins on our bodies are more visible than some, but what would you hide from the world? That your blood runs through your body? That you are mortal and vulnerable like all things?

You earned your veins by doing what you love, pumping your bike pedals or pounding your legs for speed. Testing the limits of the universe you encountered. I love you and I wish I could protect you from every difficult situation of your life. But I never could and if I had you would not be you.

——————-

Dear Mama,

How do I stay progressive as a bureaucrat? How can I sew without depth perception? How do you make a sideways French braid? How do you use an electric drill, and for what? How do you hide your wires? How do you love unconditionally? How do you put a name-dropper in his place? How do you talk to a ghost?

——————-

Somewhere in those held-breath weeks after the shock of the diagnosis, we strolled in Young’s Pond Park, our secret haven some miles from home. It was early spring and the water was blanketed in a thick layer of algae, a sharp chartreuse that strained our eyes and puckered our cheeks and stretched to the trees. The dogs pawed the edges, mystified, unable to recall the properties of water in the drone of that green.

We paused on a plank wood bridge as a swan family of five floated toward us in perfect succession, hissing the dogs back to shore and leaving a contrail of rippling blue in its wake. For a second, I thought I knew your world, full of inverted beauty—water flipped meadow, meadow flipped sky. Next to me, you exhaled a soft Oh. I could not tell if it was an expression of pleasure or pain.

In the face of this abyss, I do not get to have hope; I get to try for acceptance. I do not get time; I get moments like this to wring for all they’re worth.

I turn you into my intentionally ambiguous sage and interpret everything you say like a message from the underworld. I have spent the last four years holding your every word up to the light, looking for the lesson in Oh.

I need to know how to keep becoming even as you come undone.

——————-

Last autumn, we took you out west for what will likely be your last trip home.

The second night, you bolt up at 2 am in the adjacent twin bed. Light seeping in from a crack in the doorframe animates your inert gaze. You look wild and petrified.

Mom?

Honey, what on earth are we going to do about all this water?

Had you wet the bed? Had a flash mountain storm somehow drenched you in your sleep? Is the bathtub running? Is this a dream? My stomach lurches as I rise, flip on the light, check the bedspread and scan every inch of the floor. No water.

It seems you haven’t blinked when you again intone, Look at this water and we don’t know how to fix this.

I am inclined to agree with the second part but I try again.

There is no water, Mom, see?

I point to the dry carpet and the dry ceiling and gesture wildly toward the cloudless sky, chiming look, look, look like a toddler learning the boundaries of the world, or a performance artist pushing them. I smooth your covers over your knees and then take your limp hands in mine, the silky skin and brittle bones achingly familiar. But the water keeps rising.

You don’t know what to do either, you say, about all this water.

I stand and walk across the room, careful not to wade. At the window, moths plunk against the screen and moonlight glances off the Rockies. Soon I am whispering to no one: Where is the water?

I hear rustling and turn around to find you looking at me now, seeing me for the first time since waking. Once our eyes meet, you drop your shoulders, unthread your fingers and lean back against the headboard, still searching my face for the lie.

Are you sure there’s no water?

Yes.

Why was there water?

There never was water.

You fall silent, considering this information. I slink back over to your side of the room and onto the foot of your bed where I lay my head in your lap. After a minute or two, I feel you shiver and assume you might be freezing or spent, so I sit up. Tears have pooled in the corners of your eyes and you are shaking, not with fear or cold, but with laughter. A silent, breathless, belly-based laugh, the kind that is not intended for an audience, the kind that grips you, contorts your face and recruits all of your muscular energy. The kind that eventually rises out of the depths of your organs and into your throat.

There is no water? You roar.

Right, I say, less certain. Awed.

This laugh was the music of my childhood. This woman is my mother, surfacing in the middle of the night to say hello. A sometimes callous, often sweet, sometimes boundary-less, often ecstatic mother, who laughs and cries with abandon, as unapologetic about her happiness as she is about her hunger.

Once my shock subsides, I am laughing too—without a punch line or, increasingly, much of a choice, my fear somehow alchemizes, like yours, into gratitude. There is no water! In the dead of the night, our laughter tangles and our pitches climb until our voices rasp and our stomachs and cheeks throb sore. At the first hints of dawn, we collapse, gasping and delirious, on that awkward island of a bed.

——————-

Lately, you mistake me for one of your four sisters. Once you say, I am proud of you for coming through the generations. My name, my timeline, evaporates in my utter familiarity. Do you mean the fortitude stuck around? The stubbornness? The smarts? The copper hair, in a certain light? There are worse things than being absorbed into family.

In the abstract it’s poignant, but in your presence I can be petulant. I demand corrections: Mom! I’m your daughter, the second born, the little one. You look at my words, my mouth. I have so many sisters in this house, you sigh playfully. Do you live here too?

——————-

When people say “mourn” they refer to a loss that’s complete. But this grief is a flood that erodes you. The more I miss you, the more you retreat.

I study grief and learn it is a stress response that can produce hallucinations and create the sense of occupying a different time zone. Life corroborates these claims. One day on the A train, I look up from a book to find a boy staring dead at me. He has swiveled away from his dozing mother to ask, “Aren’t you the girl I met before?”

When well-intentioned people try to console with, “Self-care. Take time off,” I do not say, “Thanks, but what would that look like for years?”

Instead, I try to live hard enough to match the pace of your erasure, consuming buckets of coffee and wine, walking miles but heading nowhere—until my knees buckle and I stumble home. Somewhere in the back of my mind I am certain of two things: 1. I should be saving you. 2. If you disappear, I disappear too.

——————-

Dear Mama,

Once, I lived inside of you. My job was to grow arms and legs, a voice, a head, and to bump up against your walls. You gave me a name, breath and blood, a strong body and paper-thin skin and then you birthed me into this world, whole and protesting. You said: Go. Test the limits. Testify. So I went. And I tested. And I testified. When I came back, you had simplified your advice. You said: Do your life, honey. When I returned a third time, you were a red feather bobbing on a churning sea.

I keep trying to do my life. But my life looks like a picture of a life. And I don’t know how to set us free.

——————-

We return again and again to Young’s Pond. One recent afternoon, as I merge onto the highway, you lean over to ask: Honey, am I doing ok?

The question guts me, though it is barely audible, almost lost to wind. (Did it even cross your lips?)

Of course, I say, Yes! You are doing more than ok.

I do not tell you about hospital stints or inconclusive tests. That we sang Beatles songs by your bedside. That you were catheterized, wiped like a baby. That we weren’t sure you’d ever come back. I do not tell you that there is no salvation in store. That your brain has decided to testify, painfully early, to your well-lived life. That we are working on letting you go.

Because there are worse things than dying, even like this. And there are worse things than being your mother’s sister. To never have been is worse than being forgotten. When you no longer know your name, I promise to remind you as many times as it takes that you are Jet, like you fly with. And I know that you will hold onto me for as long as you can.

When my big sister was little, she dropped a slipper down a sewer grate and we dubbed it the Forever Hole. With a name, it gained a purpose and lost its menace. The Forever Hole is where your memories live now, under the surface and past our reach.

In the car, I echo your question back to you. Am I ok?

Of course, you say what you have always said, what you have willed me to be: You are so strong.

It is Sunday. In the simplified story, we are two women and two dogs speeding down a dry stretch of I-95 toward a place where we can roam free for a while. I crank up Miles Davis and gun the engine.

Nice, you breathe, and your jaw slackens as you close your eyes.

Coriel O’Shea Gaffney works as a Staff Writer in the NYC Mayor’s Office. She received her MFA from The City College of New York where she was also an Adjunct Lecturer for four years. She has been a featured poet for the Earshot!, Franklin Park Literary Series and louderARTS Project, among others. Publications include: Elephant Journal, Lyre, Lyre, Vision through Words and Scapegoat Review. Coriel is the recipient of the Jerome Lowell Dejur Award in Poetry. She is also a certified Yoga Instructor and offers workshops and retreats that combine meditation, breath work, movement and writing. Read more on corielogaffney.com.

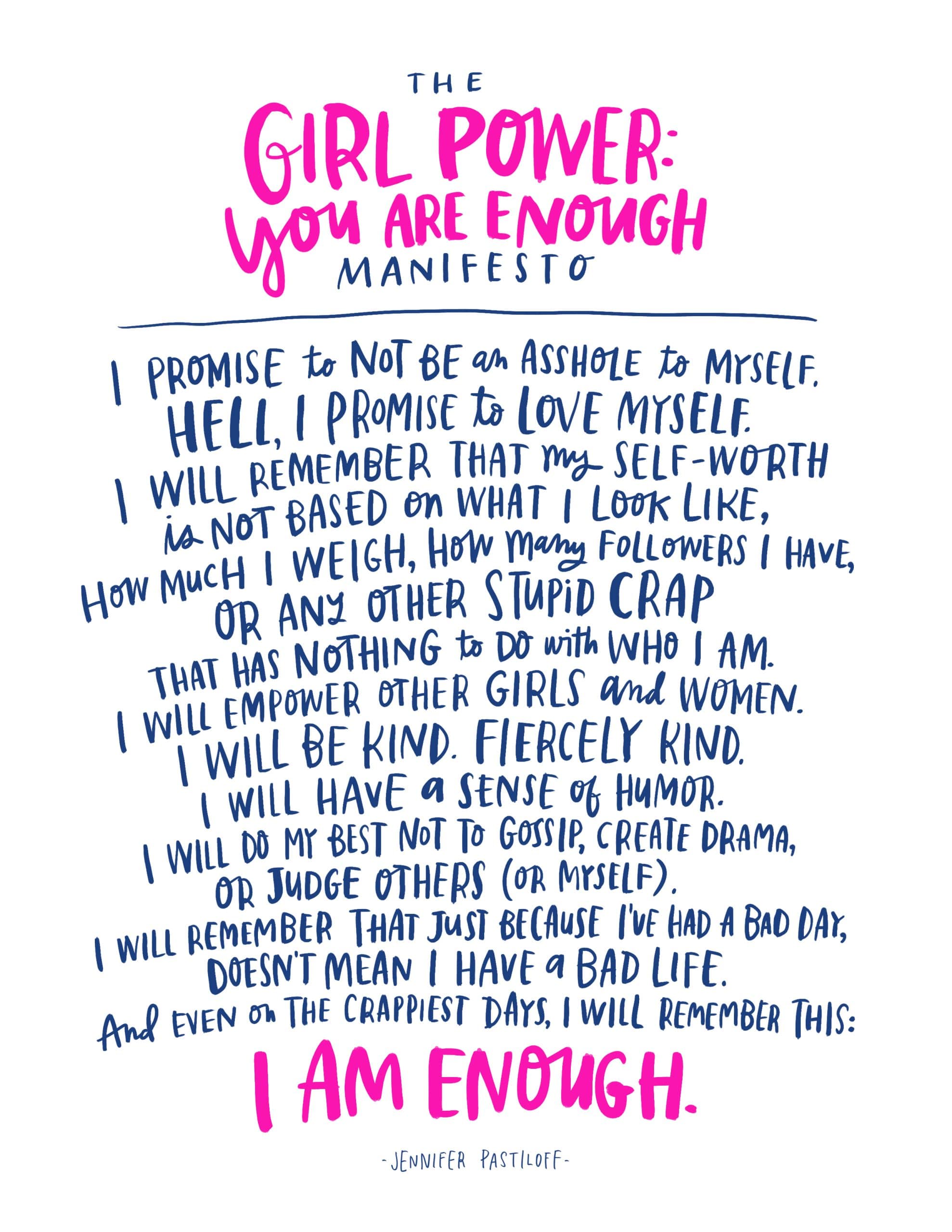

Get ready to connect to your joy, manifest the life of your dreams, and tell the truth about who you are. This program is an excavation of the self, a deep and fun journey into questions such as: If I wasn’t afraid, what would I do? Who would I be if no one told me who I was?

Jennifer Pastiloff, creator of Manifestation Yoga and author of the forthcoming Girl Power: You Are Enough, invites you beyond your comfort zone to explore what it means to be creative, human, and free—through writing, asana, and maybe a dance party or two! Jennifer’s focus is less on yoga postures and more on diving into life in all its unpredictable, messy beauty.

Note Bring a journal, an open heart, and a sense of humor. Click the photo to sign up.

Jen is also doing her signature Manifestation workshop in NY at Pure Yoga Saturday March 5th which you can sign up for here as well (click pic.)