By Stephanie Couey

When I hold it, it feels nothing like a cock. Not even a hint of cock in this piece of heavy black metal; a symbolism I had imagined would be solid and indisputable goes limp as I hold the grip with my palms, resting my fingers along the barrel. As I hold it before firing, all I can think of, is unveiled violence, and how it doesn’t, at any moment, not even as the gun goes off and hits the target I’m aiming for, feel anything like power.

My partner, hopefully the last person I have to love, and I pull up into the parking lot of the shooting range with a plastic Wal Mart bag full of doughnuts and energy drinks. He says something to me about this place being ripe with material, just as I’m thinking the same thing. I feel myself slip into the role of slimy anthropologist, knowing I’m sure to get my fill of white right wing men to observe like animals.

The parking lot in Fort Collins, Colorado is unsurprisingly full of utility trucks and oversized family vehicles. As we walk into the front room of the range, he emphasizes how important it is that it not be called a “shooting range” but a “gun club.” He tells me this is a place where people go to find a community outside of their homes or jobs, not just to shoot guns.

If I can respect anything, it’s the need for establishing community, but I wonder if I can keep myself out of the way enough to be able to see the community, and not just see my own opinions mirrored back to me in a mosaic whose patterns I think I already know. In the patterns, I’d see a row of men, shooting just after the Sunday morning service, gripping their loaded second cocks, discharging projectiles one after the other toward pieces of cardboard they envision to be terrorists, homosexuals, atheist academics, sexual deviants courting their daughters, or some amalgamation of all of them, and I could be right, but I could also not be.

We walk in, passing the living-room like set up in the front area. Plush couches are arranged before a flatscreen TV showing the Addams Family on mute (Cousin It squirms while getting a perm). Someone’s wife has made brownies, and paper towels draped over the top of them soak the grease. Ordinarily, this is where I would stay, flipping through an old issue of Family Circle or Country Living, maybe trying to nap, anticipating lunch, texting my parents and friends in other states. But I sign a liability form, don huge blue earphones and protective eyewear, and follow my partner back through the heavy sets of sound-proofed doors and into the range.

My body is jolted by the sound, even with earphones on. I expected some harmless “bang bangs,” “shoot shoots,” but I feel it in my throat, deep at the root of my skull.

My partner’s dad welcomes us back to the rows he’s set aside for us. His face is warm and lively. He nods a lot while my partner speaks, and I clutch the earphones.

Empty bullet shells pelt my shins and tennis shoes in ricocheting shimmers of gold.

I look around and there are probably five women and fifteen men. I focus on the women, maybe seeing them more clearly than the men because I’m digging for familiarity.

There are a couple of older ladies, my mom’s age, dressed as though they’re going on a brisk daytime walk in loose Adidas sweats and glowing white Reeboks.

And then there are a few teenage girls, cowgirl’d-out, done up in their version of swag, glittering cell phones hanging out of their back pockets. They poise their bodies away from the guns they’re holding, as though between it and them were an ugly boy attempting a slow dance. Their fathers watch their daisy duke babies grow up. With every increasingly confident shot from manicured hands, I imagine the bodies of dads relaxing into warmth, feeling like a protector, feeling like a father.

My partner’s dad shoots with a slight sideways stance. Even shooting he looks gentle.

My partner shoots like the cop he almost was, legs spread, leaning forward, solid to the ground.

I know I don’t want to shoot, but I know that I will.

The women smile at me. The young girls smile at me, pretty, and probably somewhere between virginal and not.

Part of me wants my dad here, so I can lie in so many ways about how protected I really am.

I hold this thing that is very much not a cock, and I shoot this thing that is very much not a protector.

I hit what I mean to hit, and I put the thing down.

The meat of my palm is sore, and my green painted nails are chipped. I think about the violence I’m capable just with my hands, small and brittle, and know it isn’t much. I’m happy to know that it isn’t much.

Stephanie Couey, MFA, is a poet and teacher at University of Colorado-Boulder. She is from Riverside, CA and Boise, ID.

Get ready to connect to your joy, manifest the life of your dreams, and tell the truth about who you are. This program is an excavation of the self, a deep and fun journey into questions such as: If I wasn’t afraid, what would I do? Who would I be if no one told me who I was?

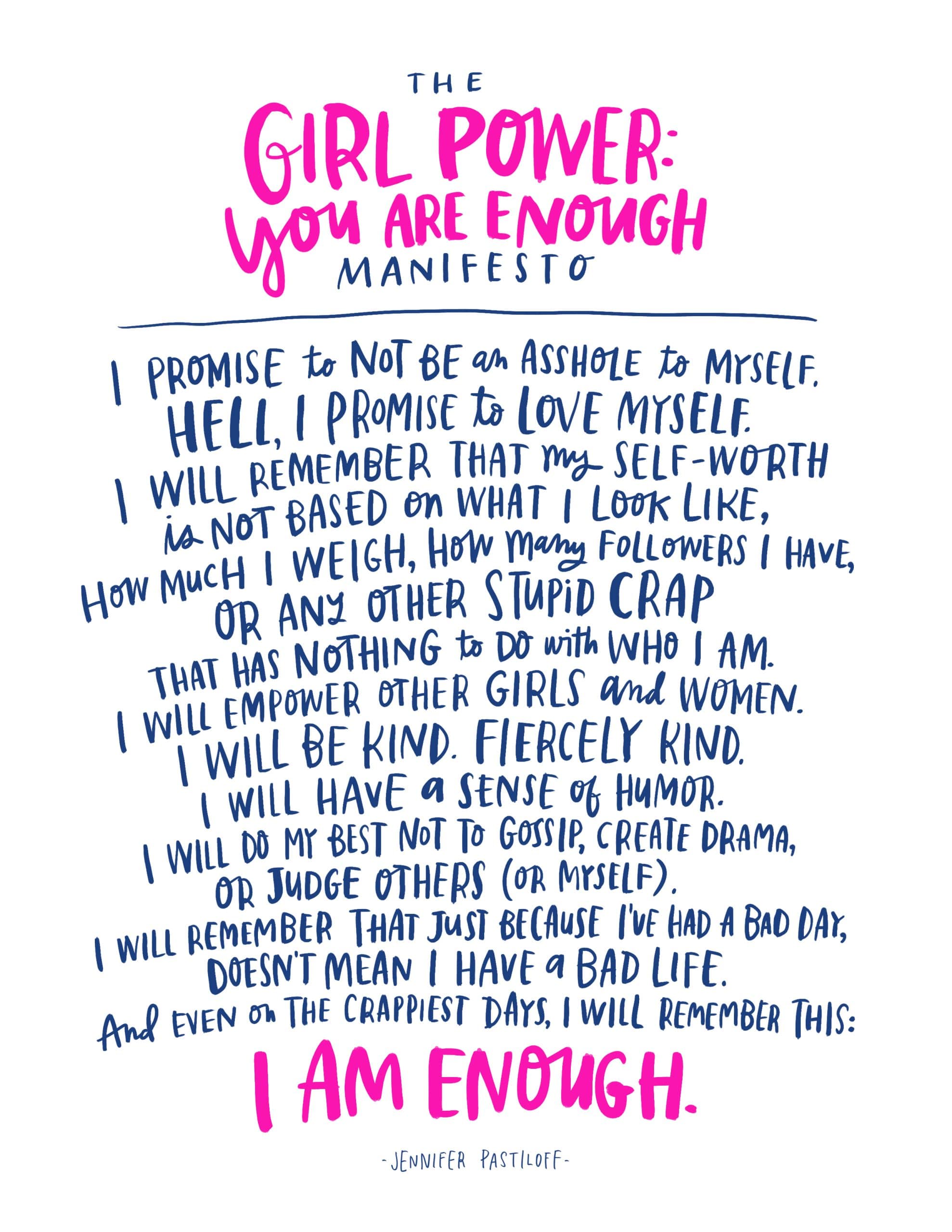

Jennifer Pastiloff, creator of Manifestation Yoga and author of the forthcoming Girl Power: You Are Enough, invites you beyond your comfort zone to explore what it means to be creative, human, and free—through writing, asana, and maybe a dance party or two! Jennifer’s focus is less on yoga postures and more on diving into life in all its unpredictable, messy beauty.

Note Bring a journal, an open heart, and a sense of humor. Click the photo to sign up.

Jen is also doing her signature Manifestation workshop in NY at Pure Yoga Saturday March 5th which you can sign up for here as well (click pic.)