By Jackie Hedeman

It started with the hot TA. In the fall of my sophomore year of college, I took Victorian Literature, and spent most of section—“preceptorial” is what we called it at Princeton, leaving no pretension untapped—fantasizing in truly PG fashion about the soulful grad student leading discussion. Tom, the TA, looked like the front man of an indie folk band. That or the eponymous hero of George Elliot’s Daniel Deronda, which we were reading that semester.

I already knew that Tom was from the Midwest, and that he liked books. Who knew what else we had in common! I got back to my dorm and hopped on Facebook to find out.

My hopes were more or less immediately dashed. “Come on!”

“Come on what?” my roommate Amy asked. She was pouring over molecular biology notes and casually singing an aria, both of which she abandoned when I spoke. I must have sounded truly forlorn.

“He has a girlfriend.” I pointed at the screen.

Amy crowded me half out of my chair and took a look. “Looks like it,” she said. Then she cocked her head to one side. “You think he has a girlfriend because he has all these pictures with this girl?”

“Yeah?”

“Well,” said Amy, satisfied, “when you become a grad student, your students might find all the pictures of the two of us and go, ‘Oh no. She has a girlfriend.’”

Amy had a point. “You’re right,” I said. “I need to gather more evidence.”

Hardcore shippers do nothing but gather evidence. They pour over the canon, and when they run out of material they turn to author blog posts, or interviews with the actors, or anyone else who can offer any insights into what exactly is going on with a particular character.

I didn’t have to delve very far into the canon that was Tom to find my answer. He did have a girlfriend, it turned out. He told us, in an offhand manner befitting the dreamboat he was. She came from St. Louis to visit and he had to end class early so that they could catch the train to New York and make their 8pm show.

I was not the only one in the class to greet this announcement with chagrin. As I left, I passed a couple of my classmates discussing the matter.

“I thought he was gay,” the first girl said. “I had this whole narrative in my head where I was going to set him up with my American Literature preceptor.”

Her friend sighed. “They would have been so cute together.”

I thought back to what Amy had said about my eventual students. It might be cool to become enough of a fictional character to have shippers. Grad students in general were bit players in an undergrad’s life. Some, like Tom, were lucky enough to be promoted to a recurring role. Shippers would mean I’d arrived.

This is how I explained shipping to my father: “It’s from fanfiction writers,” I said. “Ship is short for relationship. If you ship a couple, like, say, Josh and Donna from The West Wing, it means you want them to get together. Or you’re super invested in their relationship. Or whatever.”

There is an element of inevitability to shipping a couple, as opposed to keeping your fingers crossed or rooting for them. There is the feeling that you have foreseen the unfurling of their arc. There is the feeling that wishing can make it so.

Plenty of people already thought that Amy and I were sleeping together. Or that we should be. Amy was my heterolifemate. That’s what we actually called it. We spewed love all over each other. We took artsy photos all over campus. We went on an intersession break trip to San Francisco, just the two of us. I made her care packages. She friended my parents on Facebook. I put up with her weird noises. She put up with my light sleeping.

We were both perpetually single. We were born single and, in our more histrionic moments, it seemed we would die single. I made valiant attempts to couch this fact in terms less life-or-death. “I’m too busy to date,” I said.

“You’re not too busy to binge-watch Skins,” Amy did not say, either because she was too nice to say something like that, or because she was too busy binge-watching Hetalia for the thought to even occur to her.

Ours was a close-knit room, but Amy and I were the closest. I could count on her to go to free midnight showings with me, to meet me for dining hall dinners, to illustrate the stories I would write. I could count on her to leave me alone when I needed to be alone.

“I love you guys,” our friend Maia commented on a photo of us. There was nothing to point us toward any specific line reading, but we reached independent conclusions that this was a love of us as a unit. We approved.

“Let’s make a deal,” one of us said. I think I was the one who said it. It was junior year and we were walking back from a movie, after dark, passing beneath street lamps perfectly designed to cast a timeless, diffused glow. It was easy to imagine yourself into a narrative under street lamps like that, one of any number of characters meant for something specific.

“Let’s make a deal,” I said. “When we’re 65, if neither of us is married, let’s get married.”

“Yes!” Amy exclaimed immediately. She drew out the yes like is had nine s’s. There was a beat. “But why 65?”

“That leaves us plenty of time,” I said. “For random dudes popping up at the eleventh hour and whisking us away.” Because from the very beginning, I was thinking realistically. Because this was an actual thing I wouldn’t mind happening, so I wanted to treat it like an actual plan, and an actual plan had to leave room for life getting in the way. At that moment in time, hurrying back to the dorm after a late movie, I was looking forward to 65. It looked like we would both be alone, and there was no one I wanted to be alone with more than her.

For all the time they spend sifting over evidence, shippers don’t give much thought to logic. Josh and Donna from The West Wing was a reference my father would get, so that was the example I gave, but a different example would far better describe the shipping experience. Josh and Donna got together. That makes them a rare case, right up there with Ron and Hermione. It is much more common for shippers to ship couples who have a very slim chance of getting together in canon. “A very slim chance,” even, is generous. In most cases, they have no hope at all.

In senior year, I sexiled myself. Amy had acquired a boyfriend at the very last minute, in the April before our May graduation. He was never her TA, but he was a grad student, somehow catapulted into the main cast. As quiet and respectful as they were being, I couldn’t be in our shared space while they had her door shut. I couldn’t put on my headphones and crank up the volume and pretend they were playing Parcheesi. I felt nervous and on-edge. I took myself to the movies and saw Thor, Hanna, The Princess of Montpensier. I remember the drive to the various suburban New Jersey movie theaters, mind buzzing, and I remember the return: walking up the stairs, pausing in the hall for a breath, then loudly opening the front door.

What was that all about? Was it the change in routine, four years of habits upended as things drew to a close? Was it jealousy that she had been catapulted out of that we’re-born-and-die-alone-and-along-the-way-we-make-friends sisterhood? Was it jealousy of another kind? I tend to think not, but I also think that if I were a model heterosexual, I would be writing a different essay.

One thing was clear. Amy suddenly wanted something I didn’t provide. Right there, in the last months, we had reached the limits of our closeness.

Or had we? Shippers don’t take no for an answer. Shippers know that pesky things like trajectory and sexuality are just material to be ignored in the pursuit of a more tempting reality. Amy and I know that, too. So when we reunited in New York two years after graduation, and posted a photo of our reunion on Facebook, and our friend Maia liked it, we thanked her. We thanked her with these words, “Thanks for shipping us, Maia.” Sideways smiley face. Exclamation point.

Maia replied within seconds. “To be quite honest, forever.”

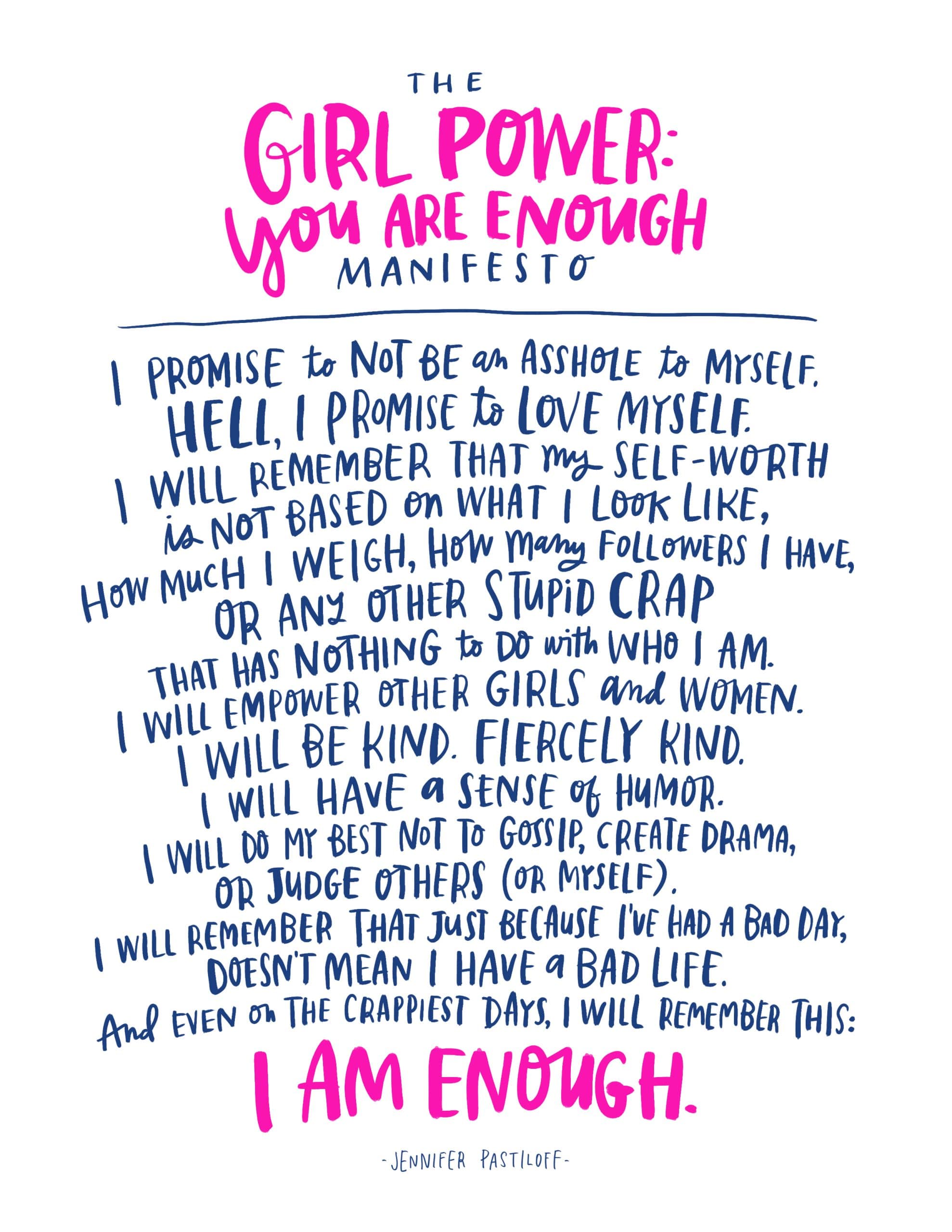

Jen is also doing her signature Manifestation workshop in NY at Pure Yoga Saturday March 5th which you can sign up for here as well (click pic.)

This is beautiful and so well-written!

I ship it.

Lovely, elegant & slyly bold. ?