By Aine Greaney

I used to tell myself that I missed no part of being a practicing Catholic–not the nighttime rosaries nor the Sunday masses nor the Easter and Christmas services.

Yet, when you grow up in Ireland, as I did, you cannot delete it all. Some mornings, for example, an old school hymn replays in my mind, so I belt it out to my fellow drivers on the southbound highway toward Boston.

Or there are those times when an American friend or colleague frets and confides about her child’s upcoming prom night and its inherent risks of binge drinking and condom-less sex. I empathize; honest, I do. But I can’t help conjuring my own convent-school assembly room where my classmates and I sat sipping tea and nibbling on finger sandwiches, waiting to be summoned to the makeshift stage for the Sisters of Mercy to bestow the little black bible that was our senior-year goodbye. I chuckle at the incongruity between generations and places, and I also know that I would gladly swap my own “prom” for something more glamorous and secular.

However, there is one part of Catholicism that I really miss: The monthly sacrament of Confession or what, since my day, got re-named as the Sacrament of Reconciliation. Confession is where Catholics get to examine their consciences, then go to church to confess and atone for their wrong-doings. Of course, this practice of atoning for our sins is not unique to Catholicism, but it’s what I have known and once practiced and, eventually, abandoned.

No, I’m not rushing off to kneel in a tiny confession box to whisper, “Bless me Father, for I have sinned.” And I must admit that, sometimes, especially in the busy season, confession felt less like a sacred sacrament and more like a morality gumball machine (insert sins; get forgiveness).

Confession box aside, though, I miss that concept, that spirit of checking in with myself, that regular and ritualized atonement for what I did wrong.

Contrition. Atonement. How archaic these concepts seem now—and how ill-suited for our win-at-all-costs society. Formal religion aside, we seem to be losing the will and skill to behold or admit to our own wrong doings.

In the past month and based on the American headlines alone, it would be easy to assume that we have lost our ability to recognize what “wrong-doing” actually is. It would be easy to conclude that ego and cowardice and money and addiction have skewed our 21st-century sense of right and wrong. Haven’t we all worked or volunteered alongside someone who would rather conceal than confess, who believes that bluster and spin substitute for accountability or substance? We’ve all honked at that distracted and dangerous driver, the one about to cause an accident, only to get that hand-sign that suggests that we, not him, were in the wrong. Last weekend, I asked a restaurant server to please exchange my dinner entrée for one that was actually cooked through. He changed it, but instead of an apology or a table visit from the manager, I got that shrug that said, another picky customer. And here’s my pet, pet peeve: the apology that isn’t actually an apology, the one that goes, “I’m sorry you feel like that.”

Yes. I know. “Sorry” ups the risk of litigation and that our opponent might win. “Sorry” means not being top dog. “Sorry” makes us fallible and human when, nowadays, we’re expected to pose and posture as infallible and super-human.

In our drive to appear Facebook-y perfect, we can’t face our own in-born character flaws or lapses in judgement. So how, then, can we confess or atone for them?

I have my own list of past and recent sins. Some of them I committed against myself and my own wellbeing. Some I have apologized and forgiven myself for. Others, the ones I still dream about at night, I have not.

In 2011, amid my country’s gut-wrenching reports on decades of clerical child abuse, there was only one shining hour: When Cardinal Sean O’Malley washed and dried the feet of some of his church’s abuse victims.

From the boardroom to the courtroom, to the halls of state and national government, we would do well to remember that admitting we are and did wrong reflects human strength, not weakness.

In our own kitchens or bedrooms, there is no more redemptive and relationship-saving gesture than to face our spouse or partner or close friend to say: “Bless me sweetie, for I have sinned. For this and for all my transgressions, I am truly sorry.”

Aine Greaney is an Irish expatriate writer living in greater Boston. Previous placements include The Manifest-Station, Boston Globe Magazine, Salon, Feminist Wire and others. Follow her on Twitter @ainegreaney.

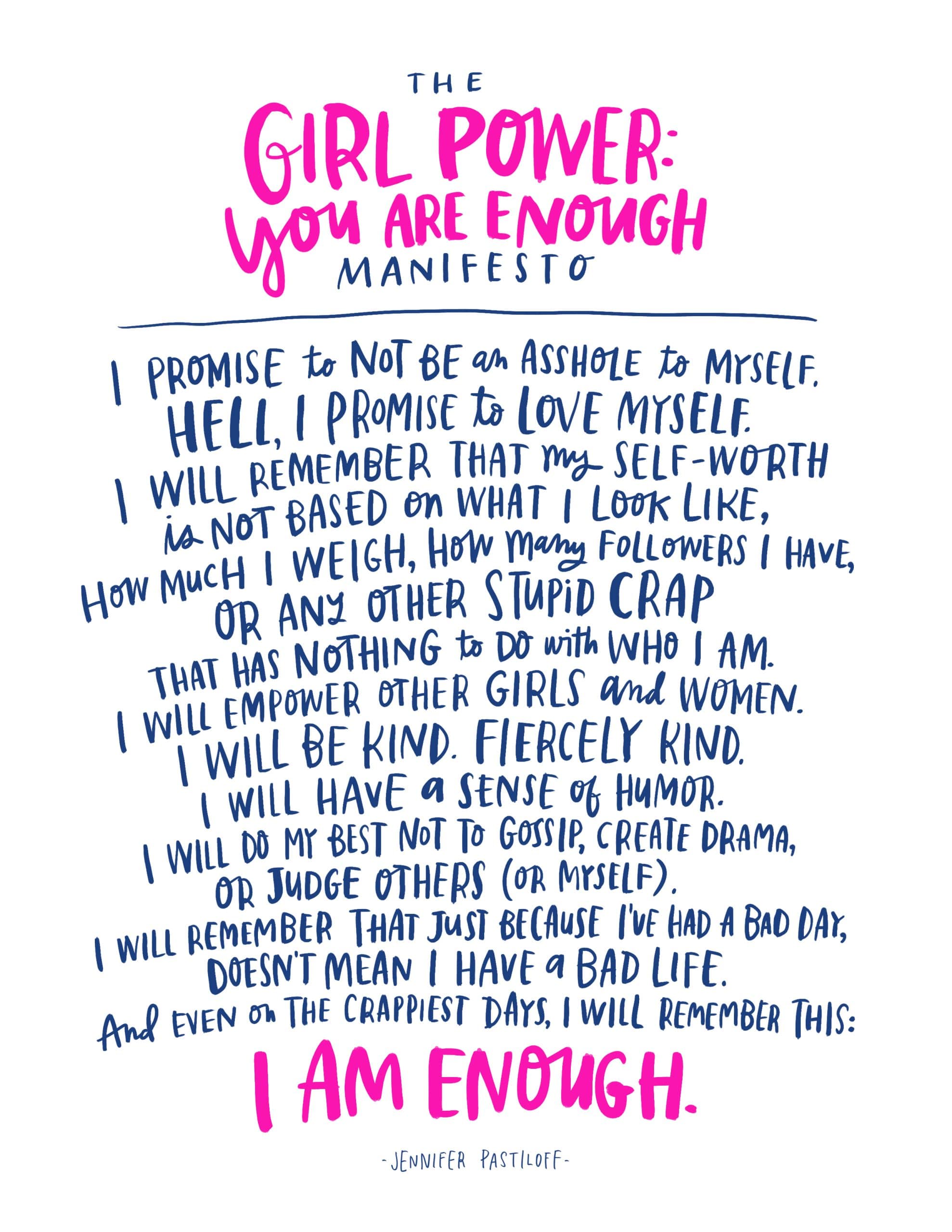

Jen is also doing her signature Manifestation workshop in NY at Pure Yoga Saturday March 5th which you can sign up for here as well (click pic.)