By Kerry Cohen

The day my mother left, I was eleven years old. It was July, 1982. In just a few months I’d be twelve. And then thirteen. And so on. Life would move forward, even though my mother had left me. I could not fathom such a thing then. I would grow up. I would become a teenager, an adult, a wife, a mother, a divorcee. I would become all of these things, even though my mother had left me.

A year earlier, my parents had divorced. Their split was ugly and destructive. My father ran first, an expert escapist, and my mother was forced to stay. She spent much of her time crying, sometimes even wailing. Her emotions were like a haze in our large suburban New Jersey house. They were everywhere. I couldn’t duck them. I couldn’t squeeze myself around them. So, instead I held my breath. I made myself invisible. I stayed on the edges, watching my mother’s every move while she did things like lay four tons of bluestone into a cement patio. She played racquetball and took up sailing. She drove us to school, her eyes wild with plans, cut off other drivers, yelled, “Fuck you, too!” when they flipped her off. I was terrified of what she would do next.

She took pre-med courses at Fairleigh Dickinson. Locals called it Fairly Ridiculous, but my mother didn’t find that funny. This was serious business. She was changing her life, no matter the cost. The things she did find funny made her laugh too loudly, too shrieky, too off-time.

When she didn’t get into medical school in the States, my grandfather, a doctor, connected her with the head of the international medical school in the Philippines. The Philippines! Do you see? How impossible this all was? The day my mother left, she went to the Philippines. The other side of the world. I could not conceive of her there, of myself without a mother. I could not conceive of a world in which I lived in New Jersey and my mother lived somewhere unknowable, and for this reason everything would become unknowable as well.

The day my mother left, the world became unsteady and too big, like a wind tunnel in which you float and flip, unable to be contained. I was flung into the galaxy, alone and untethered. The only thing I would find that was heavy enough to hold me down was a man. And my God I wanted that, a man pinning me to a bed, even then, even though at eleven I couldn’t quite put the desire to words. I was eleven, but the yearning began then. The day she left. The day she left my fate unfurled before me like a fluttering ribbon. I would follow this yearning for years, for way too many years.

I don’t remember the day my mother left. My older sister doesn’t either. Once, much older, I asked my mother about that day. My question was careful, devoid of emotion. I didn’t want emotion. I didn’t want her to cry. I certainly didn’t want to cry. I simply wanted facts that I didn’t have stored in my long-term memory. I didn’t know that day, as I know now, that memories are formed and consolidated through the hippocampus, a seahorse-like structure that is part of the limbic system in our brains. Through the hippocampus we develop what is called ‘long-term potentiation,’ which is the strengthening of the synaptic connections that lead to memory. These are the facts. I think of this now, that small sea creature in my brain, how it dove away, how nothing was strengthened except a vague sense of dread that I carry to this day. There are times when I feel certain that if I could recount the moments of that day through my own memory I could find the important thing that got lost that could free me, like a key dropped into a sewer grate.

My mother called every Sunday after nine when the rates went down. I answered her questions with single words. Yes, no, okay. Talking to my mother was like walking on glass. Careful, careful, don’t slip or you’ll hurt yourself. I spoke to her as though from a narrow hallway where I had to stand perfectly straight, perfectly still, lest something get unleashed.

In high school, I defended my mother fiercely until one of my friends said, “Why are you defending her? She left you!” In college, I mentioned my mother once, and a friend said, “I didn’t think you had a mother.” I wrote a short story that began, “The day my mother left,” and my professor told when she read those words she knew this was the story she had been waiting for me to write. Years later, revised a thousand times, that story was my first published piece.

The day my mother left was so long ago. It’s a tiny dot seen from outer space. It’s also an infinite thing, an actual space that lives inside me. My sister says she has one too. Somewhere inside this space is the day itself, the thing that actually happened. It is on repeat, this non-thing thing. The day my mother left, the day my mother left. It goes on and on, unviewable, unreadable, but there.

Here are more facts: The hippocampus is located next to the amygdala, named for its almond shape, which is responsible for experiences of fear and sadness, and also plays a role in how we process emotional aspects of events in our memory. If the amygdala overloads from too much fear, too much sadness, it will turn off this function, disallowing any memory of the event. This is to protect the brain from having to process something it can’t. In the memory channels, then, it is as though this event never happened. And if it never happened, if my mother never left, then this is my life either way. In all possible interpretations of this day when my mother did allegedly leave, I still become a person who pines for a mother, who spends her life trying to tie herself to something that is heavy and strong enough to stay.

The day my mother left, she didn’t leave. The day my mother didn’t leave, she left me. My mother was always going to leave. I was always going to be left.

The day my mother left didn’t happen.

Once, I held my son, cradling his sweet, animal flesh, his tiny human form sprung from mine, and I cried for the mother who left her child. I cried for her loss, because to lose my baby was unthinkable. It literally could not be a thing. My mother lived a life in which she left her children. I would not. And as much as I knew I didn’t have to hold this for her anymore, it was not possible for me to not hold it. Her leaving is me. The whole world that began on that day my mother did or didn’t leave is me. Even my mother, she too is me.

This is the story my mother told me: The day my mother left was a July day in 1982. My grandparents drove my mother, sister, and me to JFK International airport. We went together to the gate, and when it was time to board, my mother cried. She held tight to my sister and me, who were both expressionless, and then she walked the jet way to her plane. My grandparents, my sister, and I watched as the plane pulled away and took off into the clear, cloudless sky. She doesn’t remember if my sister or I cried. She doesn’t remember feeling anything other than excitement and fear.

Last year, I found her journal from that time. I searched for the day she left, but it wasn’t there. There were entries that were indirectly about that day though. She wrote, “Nothing will hold me back. Nothing!” She wrote, “I wonder if I’ll miss the girls?” I took photos of these entries. They sit on my phone as evidence, but of what I’m not sure.

I remember living with my father in a new apartment big enough for him, my sister, and me. I remember requesting that my room be painted hot pink, which it was, and which the following year I regretted, cursing myself for having picked such a childish color. I hung posters of James Dean. I had a view of the George Washington Bridge and the Manhattan skyline, and I regularly imagined that my life could finally begin if I could just grow up, cross that bridge, and find the things waiting for me.

I remember there was a boy in the apartment building with shaggy blond hair who wore the same red shorts everyday. I had a crush on him, my first crush of many. I remember feeling certain that boys weren’t interested in me, that I wasn’t pretty enough, I wasn’t thin enough, I wasn’t unique enough. I remember taking up smoking. I remember smoking my first hits of pot. I remember dressing in clothes that were too provocative for my twelve-year-old self and going with friends into the city to find boys. I remember feeling both frightened and excited by boys, by their alien bodies, their beautiful and strange ways in the world that seemed so different from mine. I remember thinking almost solely about boys, how they would free me, how they would save me, how they would make me mean something more than the fact that my mother had left.

I remember these things.

I remember believing with my whole self that a solitary boy could take up the space that had been left by my mother’s absence.

People say, let go of your past. They say, move beyond it. I have tried. I’ve tried yoga, meditation, therapy, positive thinking, self-help books, writing, prayer. I have tried starvation, pain, alcohol, drugs, sex, love. I have imagined digging it out with a garden spade, cutting it with scissors as though it were excess fat. But there it is: the day my mother left.

The day my mother left, she left me also with an absence, a space, a thing that would always be mine. She left, and in her place was a gift of yawning want that I carry with me like a precious stone. This is my story. The day my mother left is a story. It is every story I’ve ever written. I can write 500 stories, but they will all begin with the day my mother left. It is the only story. It is everyone I’ve ever loved. It is everyone I’ve ever lost. It is everyone I’ve ever left.

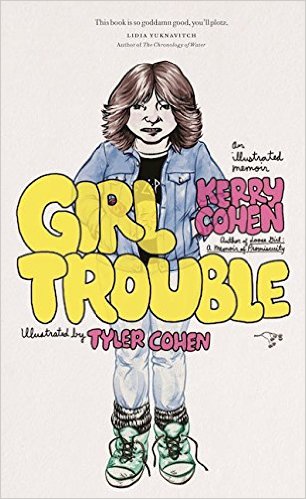

Kerry Cohen is the author of 9 books, including Loose Girl: A Memoir of Promiscuity. Her next memoir Girl Trouble: An Illustrated Memoir will be out in October 2016. She can be found online at www.kerry-cohen.com and www.kerrycohentherapy.com

Kerry,

Thank you. You are the first writer to come even the slightest bit close to sharing a story so similar to my own. One I’ve found impossible to tell. A story about MY mother leaving. Your first sentence grabbed my attention and didn’t let go. I am deeply aware of the feeling… to be willingly left by one’s mother. I never saw mine again. I too had a sister. I wondered the things you wondered. Was it hard? How could she? What if? These questions, with no answers, have weighed me down all my life since ‘that day.’

Thank you for sharing. Thank you for writing. Thank you for knowing.

~Melissa

Cohen – The Day My Mother Left Me

Thank you, Kerry. Beautifully written. Inspires me to write to heal myself.

I can’t even speak! I’m so touched by your story. It is also mine. Only my mother died. But in that long-ago time, children weren’t considered … no explanation, no goodbyes, no nothing. The hole that never fills…the longing, the sense of abandonment. You’ve touched me on a very deep level.