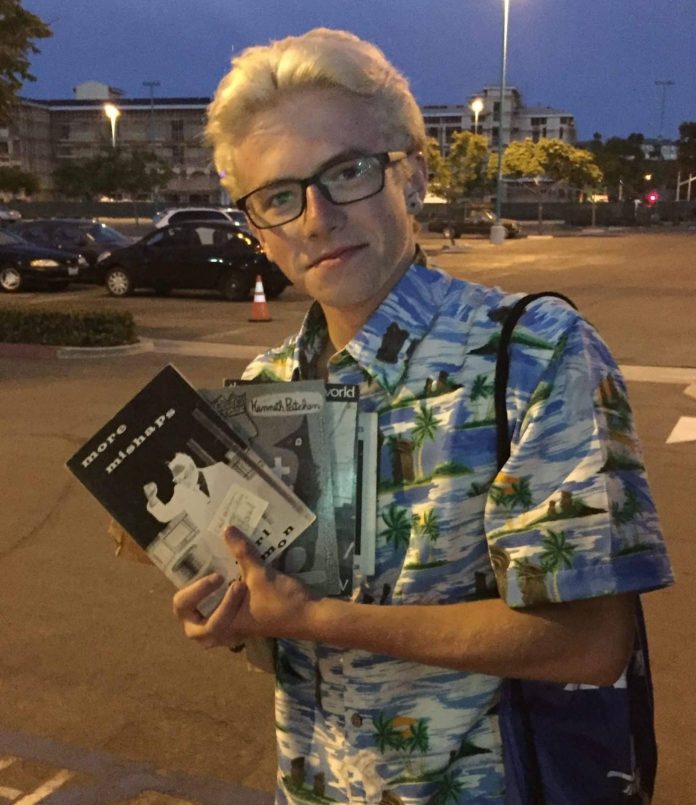

*Skyler with his beloved books

CW: This essay discusses suicide. If you or someone you know needs immediate help, please call 911. You can also call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at: 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting CONNECT to 74174. The world need you.

By Cati Porter

I am trying to remember the first time I met you, Skyler. Instead, images of you float up out of random events:

— Sitting on our bench swing in front of the house, texting Jacob to tell him you were there, because, well, teenagers.

— Both of your arms in casts, broken from leaping down a flight of stairs.

— In our living room, rocking chair, holding a book from our bookshelf.

I so loved that you loved to read. The Beat writers you loved best. We would talk about Burroughs, Kerouac, Ginsberg. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. I loaned you my copy of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. You were already thinking about dropping acid? I didn’t yet know you loved the Grateful Dead.

You were the kind of teenager I had imagined my own son would be, but Jacob was different. He had sworn off books. But with you, your influence, that seemed to be changing.

It’s been almost a year, to the day. Every story has a beginning, middle, and end. Sometimes it’s difficult to tell one from the other, right?

I am a writer. It is how I make sense of things. Please be patient with me.

*

I had just walked in the door after hosting an event for writers. It was a Thursday night in May.

“Mom — Don’t freak out. Skyler took all his pills and he’s on Target Hill.”

Jacob rushed down the hallway toward me. I hadn’t yet put my purse down. It was dark outside – 9 pm. Bedtime. His hand was on the knob at the front door, knit cap pulled low over a mess of knotted curls. He was looking at me for — permission?

I was immobile. My chest. My legs. My face. I did not cry, not yet, though suddenly it felt as if I were behind a wall of plaster. I was moving inside a plaster cast, heavy and numb, like those dreams where you can’t move fast enough. Without thinking, I told him, “Run!”

I pulled the door in behind him as he took off and I dialed 911. It rang. I could hear a woman’s voice:

“Please state the nature of the emergency.

I could already hear the sirens. I drove recklessly. I’ve never before heard sirens and knew so achingly, precisely, where they were going. I pulled up behind the ambulance, threw it in park, jumped out. Normal things like careful parking, lipstick, proper shoes, became trivial, as they still are. Sometimes it takes something jarring to shake you loose.

Though I could not see you, I knew Jacob must be sprinting up the brush-covered hillside in the dark, no flashlight.

At the base of the hill, I could see the fire engine and ambulance that arrived before me. There was a gurney waiting. Two paramedics on the sidewalk, dark suited, faced the hill, watching the brush for movement.

And then, after forever, I could see Jacob leading you down the hillside. Relief rose in me against the panic of what I realized I might have sent Jacob to find.

Another car careened around the bend, at a strange confluence of streets: Dominion Ave and Division Street. The car slammed into park. It was your dad.

Car door swung wide, he got out and began to pace. I had never met him in person before. He was so wiry, tense; intense. Every muscle in his body seemed clenched, his face drawn, hands in fists. All I knew of him was through you, what you had told me. He stood facing me, waiting for me to speak.

“He’s alive,” I said, pointing to where you and Jacob were just reaching the road.

Your dad and I watched the both of you in silhouette against the night sky, gingerly descending. It looked like Jacob was holding you up, the two of you navigating the loose brush and rock. It was then that I put my arms around the neck of this man, your father, a stranger I have only ever spoken to over the phone. I held him as he cried, this tough ex-soldier. He was not at all how I had imagined him.

Jacob walked you over to the paramedics. By now, you could hardly stand. The paramedics lifted you onto the gurney like a loose, sleepy child into bed. I don’t imagine you could remember that. I leaned down to kiss your faded pink fluffy hair. You looked stoned, wasted, delirious. I said, I love you, Skyler, and meant it. Your eyes were open but you were non-responsive. I had never said anything like this to you before, and never since.

Jacob tells me that he had pulled you to standing, too weak to object. He had found you sitting on a rocky outcropping, woozy. You said something like, “It’s okay. Sit with me,” patting the stone. Jacob told me later that he had said no, that he wouldn’t let you die there. That if you were going to die you would have to get down and do it in the ambulance.

At that point, you were moments away from a series of seizures that would require an induced coma to keep you safe for the next few days. What was it like, to be unconscious for days? A little like death? Did you dream?

Jacob, your dad, and I stood by the side of the road for a little while after they had gotten you into the ambulance. Jacob was quiet and seemingly calm though I knew his pulse must have been racing. The ambulance started to pull away. As I said goodbye to your dad, ready to follow, I implored him, this time, no tough love; this time, please: Only love.

*

The last time you attempted suicide, your girlfriend had just broken up with you. Wasn’t it on Valentine’s Day? I wish we had been able to talk about it at the time. It’s never easy to get your heart broken.

I didn’t learn about it for three days. All I knew was that you had been throwing up, and that Jacob hadn’t heard from you, which struck me as odd considering how close you were. Later, Jacob told me that you had said over the group chat that you’d taken some pills and were throwing up. I’m glad Aaron had the presence of mind to call your dad, and 911. Did they pump your stomach? I think they did. And you were held for observation. On the third day, your dad called all of your friends together after school, huddled up on the sidewalk of the neighborhood by the high school. I had a horrible sense that something was wrong. I pulled up just far enough to be out of sight but I watched them squirm, listening to your dad, in the rearview mirror.

What I didn’t learn until later was that you had given notes for all of your friends, including your girlfriend, that began, “If you’re reading this now….”

*

This time, rather than seven pills, you have taken seventy-something. All of your anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medications.

In the ICU, before you completely lose consciousness, you send Jacob a loopy string of text messages. You say that you want to have a cheeseburger with Jimi Hendrix. You say that since you are still here, you must be here for something. You say that you want to be a crazy writer. Like Ken Kesey. Hunter S. Thompson. And I think, maybe you’ll be okay.

Then, the texts stopped.

The next day, Friday, Jacob says he can’t go to school. I let him stay home and together we wait for news of you.

They keep you in the coma all that day. On the surface, I am keeping my shit together. Beneath the surface every worst thought.

That space of not-knowing, it is excruciating. I leave Jacob at home and go to my office, but I can’t focus. I go into the storage room out back to call my friend Gayle, where I cry hard and long, my face smeared with snot and tears. Her mother had committed suicide by hanging. My problems felt trivial but I knew if there were anyone who would understand what I was going through, it would be her. You weren’t my son, but it crushed me.

I needed something to focus on, something to give me to do while we waited to hear news of you, so she and I hatched a plan. I knew it might sound crazy, or stupid, or useless, but I decided that whatever the outcome, I must do it. She said she would help.

Do you know that there is a high correlation between writers and depression, writers and suicide? I thought you might appreciate that.

*

Over the weekend, I receive regular text updates and phone calls from your family. By Saturday, the seizures taper off, so they bring you up, but, they say, you may or may not have sustained brain damage.

When you wake up, you tell us you can’t remember anything of the days before, but remarkably you seem intact.

You relay to us some of the things you thought you saw while you were out: You believed it that if you stared at the clock long enough, that it would turn back time. The nurses faces melted and morphed into demonic faces.

You seem bemused as the events of the past few days are relayed to you, like you are listening to funny anecdotes about strangers. By Sunday, still in the ICU, your dad says you are ready for visitors. He adds us to the list of family allowed in to the hospital room. If we weren’t family before, we are now. Your sisters keep telling us how Jacob had saved your life. For all the times you have complained about them, I think they idolize you. You are their big brother and they are glad to have you back.

Jacob and I plan our trip to Riverside Community Hospital. Remembering the cheeseburger, I call the nurses’ station to get their okay. We drive through Jack in the Box. Jacob of course knew just what you’d want. When we arrive, you are sitting up in the hospital bed, and your sisters are around you. Your pink hair is disheveled. They have assigned you a “watcher”, someone to be with you in the room at all times, making sure you don’t try to hurt yourself again.

You are elated by the cheeseburger & root beer. Jacob sits across from you and you talk as though nothing has happened. You want to know what’s been going on outside, what your friends have been up to.

When I ask you – we all ask you – if you are going to try this again, you tells us that you are taking it “twenty-four hours in a day”; a puzzling response. It sounds equivocal, but we accept it.

After a little while of sitting and watching these friends, I pull out the book I’ve compiled and carefully bound: Letters to Skyler from Fellow Writers.

In the past twenty-four hours, I have called upon friends and strangers, all writers, to send notes of encouragement and hope — depressed writers, suicidal writers, writers who have suffered through suicide loss. Jacob thought it was a dumb idea but as he watched you page through it, the look on your face, he later said that it was, in fact, a good thing.

They move you from ICU to a regular hospital room, then from there to a mental health facility for adults, because while you’re still only a junior in high school, you are eighteen. I am told that it is a section 5150 hold, aka the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, followed by a 5350, an involuntary hold for those with a mental disorder who are a danger to themselves or others. These are not unfamiliar terms. Jacob’s uncle, my husband’s brother, also struggled with many of the same issues that haunt you.

There, Jacob tells me, you took up smoking, and kept a journal: “Diary of Mad Man.” Though your dad didn’t want you to have any contact with your friends, we encouraged Jacob to call you, which he did. When the high school released you for the year, we were glad, so close to the end of the school year, and with your ex-girlfriend there, we weren’t sure what you’d do.

When you finally go home, as promised, I give you my old typewriter. I bring you enough ink & correction tape to last the rest of high school.

Over the summer, things get better. You read a lot, and even write. This makes me happy. Old out-of-state friends come to see you. You took a trip to Venice beach. I am glad when you accept our invitation to go with us on our family vacation to San Diego. You bring your roller blades, Hawaiian shirt, and the Nixon mask. When we talk about the future, you give me hope.

Everything is fine now.

Summer passes. It is time for you to register for senior year. On a Monday morning, Freshman registration, when I registered Bradley, Jacob tells me you registered early. In fact, you tell Jacob you shouldn’t have registered at all.

Wednesday night, you go to the drive-in with your dad and sisters. Late that night, you pull the cans to the curb for trash night, say goodnight,I love you, to your dad.

Thursday morning, August 25, 2016, is the official registration day for seniors. Jacob and Bradley are sleeping in and I am speaking with a landscaper on my front lawn, discussing tree removal and grading and water-wise gardening.

Then, my phone rings. I let it go to voicemail. It rings again.

It is your dad. “He’s gone.”

I don’t have words to describe how it feels to hear those words. He tells me you have hung yourself in the bedroom closet sometime during the night.

Playing in the background, The Grateful Dead: “If I Had the World to Give”, on loop, the same song playing over and over and over.

There in my front yard, in front of this stranger who hugs me and holds me as I curse and cry, I fall apart.

At that moment, I can’t imagine going in the house and waking Jacob to tell him. But I do.

Your dad tells me that when the coroner and sheriff arrived, they found no foul play; of course not. None of us had any doubts. It was awful to think of them using your lifeless finger to unlock your phone, search for “clues.” Of course, we immediately drive to your house. Jacob and I sat on either side of your dad on the couch, arms over his shoulders, the three of us sobbing. If you had been there — you were there? — we would have been a sight.

Sometime during that final night, we learn that you had messaged Penny in Seattle: “Are you awake?” No response. That was the last word from you to anyone.

Later, Penny messages the instructions you had messaged her. She honored your wishes to send it to Jacob, “should I lose this battle.” Penny kept her promise. It detailed who should get what, including that Jacob should get some of your ashes: “Put them in a pipe and smoke it or I will haunt your ass.”

In the days following your death, I learn that together you and Jacob have tried LSD, sitting on that same rocky outcropping where he found you that night.

When your dad reads the note, it is only then that we all realize that you have been planning this all summer. All of your friends seemed to feel your death was “inevitable”. They knew the end was coming. Jacob knew. But they kept your secrets. I want to hug them. I want to slap them. I want to stare at that clock until the hands spin back to before.

Your dad says that Jacob can smoke your ashes, but only if he wants to, and only in your bedroom, with him, while telling him stories about you.

Instead, Jacob orders a pendant — an eagle, to match your dangling sterling silver earrings. The day before your death, we learn that you’ve lost one of them, walking through our neighborhood. In the days after, we walk for hours, scouring every glint in the dust. Later, we learn that the mortuary has misplaced the other. This is a blow. This feels like metaphor.

The last time we see you alive, we are driving past, headed elsewhere, always in a hurry. Jacob stuck his head out the window and shouted. You waved goodbye. The next morning, you were gone.

Now, Jacob carries a small piece of you around his neck. You went to his graduation — wherever he goes, there you’ll be.

The other night, I asked Jacob if he still thinks about you. He says every day. That you come to him in his dreams every night.

Your dad thanks me, because he thinks those letters gave you two one last summer.

I thought words could save you. But maybe, in some small way, these words are saving me.

We are proud to have founded the Aleksander Fund. To learn more or to donate please click here. To sign up for On being Human Tuscany Sep 5-18, 2018 please email je*******************@***il.com.

Oh, this is so beautiful. Thank you.

This is very important and real. Thank you for your enlightened perspective on this subject.

Thank you.

My Lydia 23 took her life . it will be 2 years January 20th 2018 this pain is so unbearable. I can’t wait to die to be out of this pain