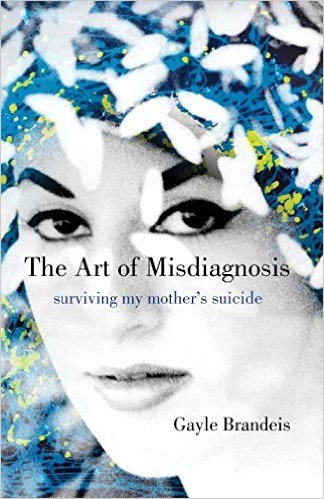

The Art of Misdiagnosis is out this week, buy it here, or at your favorite independent bookseller.

By Angela M Giles

Gayle Brandeis is an amazing writer of poetry and prose and I have been waiting for this book from the moment she announced the project. Although I truly enjoy her writing and look forward to whatever she publishes, Gayle and I share a strange commonality that made me especially keen to read this- we both lost a parent to suicide. Our losses occurred under very circumstances to be sure, but she and I experience a type of grief that is still a bit shadowy in our culture, and it is a grief that is wildly complex. I was curious to see how she was approaching the subject and what she would make of the story of her mother’s suicide and of her own survival in the face of it. It’s a complicated emotional space to be sure, and in this book Gayle navigates it with grace and clarity and honesty. This is an important work, and not just in terms of grief literature. You can also read it for a discussion of family dynamics, or a discussion of mental illness…just read it.

I asked Gayle about her mother and what she would say to her if she could give her a copy of the book. What would she want her mother to understand about why she felt the need to write their story? This is her response:

“I would first say Thank you. Thank you for supporting my writing since I was a little girl, even though you never wanted me to write about you. Thank you for giving me a love of books, a love of art, for giving me the knowledge that books and art can be a container for our inner lives. I would say I know that reading this book will be hard for you, but I hope you will come to understand why I had to write it. Writing is the way I make sense of myself, make sense of my world. If I hadn’t written this book, I would be in much rougher shape. This book has given me so much. It’s returned my faith in myself, in my own strength. And it’s brought me back to you. It truly has. If I hadn’t written this book, I wouldn’t feel as close to you as I do now, perhaps closer than I ever have, other than when I was very, very young. It’s helped me appreciate you so deeply, helped me see what a creative badass you truly were. Our relationship was such a complicated one, but writing this helped me get back to a place of simple, profound love for you. When I hand you this book, I’m handing you my heart. I hope you will receive it in that spirit. I hope you can tell that, at its core, this book is the truest love letter to you I could ever write.”

Thank you, Gayle, for sharing this love letter with the rest of us.

Excerpt from The Art of Misdiagnosis:

Dear Mom,

My therapist suggested I write to you. She thought it might help me find some clarity, help me understand how I am feeling about everything. It’s good advice—I often don’t know what I know until I write it down.

I wish I knew where to begin.

I suppose I could just write

WHY?

in giant letters smack in the middle of the page and leave it at that. I could be more specific: “Why did you kill yourself?” But even that would be too easy. Besides, I have too many other questions. Questions about our family’s relationship with illness. Questions about our family’s relationship with silence. Questions about your own relationship with your family. Questions, questions, so very many questions. Questions you’ll never be able to answer.

It’s always been hard to talk to you.

You gave me and Elizabeth an idyllic childhood in so many ways—I’ll forever be grateful for the freedom we had to play and create and explore, for the family vacations we took to places like Disney World and Washington, DC, for the way you exposed us to museums and concerts and good food, the way you drove us to figure skating and dance classes, the way you made us feel our possibilities were limitless. Once I hit thirteen, things fell apart, but I had a practically perfect childhood. Still, even then, I didn’t know how to talk to you.

I do know when that started. I was five years old. You had just eased your brown Chevy Impala into our spot in the communal parking garage under our apartment building in Evanston, Illinois, the spot you could glide straight into once the metal door clanked up on its track. The best spot, and it was ours. I suspected this made us the royalty of the building; I felt sad for all the other residents who had to back into tight spaces hemmed in by concrete pillars. You cultivated that feeling in us from the start—the sense that we were special, royal.

The garage was cool and smelled of leaded gasoline when I opened the back door; I took a deep breath, the scent as delicious to me as bread, and tried not to pay attention as you quietly got more and more upset. I wish I could remember what I had said to you; I remember everything from this moment except the words that set you off. They couldn’t have been too bad—I was always careful with my speech—but you yanked the green and white Wieboldt’s shopping bag off the floorboards, plucked Elizabeth from her car seat, and tore toward the door that led to the elevator.

“You never say anything unless it’s something mean about me,” you snarled. You had never spoken to me like that before. You had never said anything to indicate this is how you saw me: a girl who didn’t speak except to cut you down. I thought I had always been your special flower, your good, smart girl, but now I knew you had been harboring a secret grudge against me. Now I knew you saw me as the enemy.

I trailed behind you and felt something slide shut across the inside of my throat, heavy as a manhole cover. It took me years to pry it back open, years before I could speak freely again. Not that I ever could around you; I wanted to, Mom, I really did, but something shut down inside me when you were around, some vital gleaming part.

I think of Gaston Bachelard: “What is the source of our first suffering? It lies in the fact that we hesitated to speak. It was born the moment we accumulated silent things within us.” That moment in the garage was my moment, the moment I started to accumulate silent things. So many are still hoarded inside me, packed against my rib cage, settled in my gut.

It occurs to me now how strange it is that I felt silenced by you in a parking garage and you silenced yourself in a parking garage almost four decades later. Both of us in the bowels of apartment buildings, cutting words from our throats. I still have breath in my lungs—a gift I don’t want to squander, a gift you tossed away—but sometimes I can feel the weight of that manhole cover clank back into place. Maybe writing this letter will help remove it for good.

Excerpted from The Art of Misdiagnosis: Surviving My Mother’s Suicide by Gayle Brandeis (Beacon Press, 2017). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

If you are feeling suicidal, help is available. You can contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at: 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting CONNECT to 74174. The world needs you.

We are proud to have founded the Aleksander Fund. To learn more or to donate please click here. To sign up for On being Human Tuscany Sep 5-18, 2018 please email je*******************@***il.com.