A note from Angela: Gayle Brandeis is a person I cherish, not only because she is an amazing and brilliant and generous human, but also because she and I share a bond I would not wish on anyone. I had the opportunity to talk with Gayle about The Art of Misdiagnosis, surviving my mother’s suicide at the Coachella Review and that important book remains on my list of books I would read again. Gayle has just released a book of poetry and Manifest-Station alum Alma Luz Villaneuva took time to speak to her about it. This is their conversation. Enjoy.

Introduction:

Alma Luz Villanueva and Gayle Brandeis first met in 1999 when Gayle entered the MFA Program in Creative Writing at Antioch University, Los Angeles. Alma became her mentor, and later, when Gayle returned to Antioch as faculty, they became colleagues; through all of it, they have formed a deep, nourishing, forever friendship. When Alma’s novel Song of The Golden Scorpion, came out in 2014, the two of them discussed it here; now they have come together here again to discuss Gayle’s new novel-in-poems, Many Restless Concerns: The Victims of Countess Bathory Speak in Chorus (A Testimony), in which Gayle gives voice to the hundreds of girls and women killed by Countess Erzsébet Báthory of Hungary between 1585 and 1609. The ghosts of these girls and women speak in chorus, compelling us to bear witness to the violence enacted against them, and to share their quest for justice—not only for themselves, but for all girls and women to come. A lyrical, polyphonic protest against silence, Many Restless Concerns speaks to today’s upswell of voices claiming their own worth.

Alma Luz Villaneuva: I was very moved by your testimonies, these so alive voices, these murdered/tortured girls women, centuries later, within your book, Gayle. First of all, what inspired you to hear these voices? How did they come to you? I often receive a dream from a character, announcing their arrival. And these voices arrive four centuries later, so alive, each one. Also, how did Countess Bathory come to your attention?

Gayle Brandeis: Thank you so much! When I was pregnant with my youngest son, my daughter, who was almost 16 at the time, was fascinated by notorious women of history, and asked me to buy several books about women pirates and other outlaws. I was idly thumbing through one of these when I found a chapter about Countess Bathory, who I somehow had never heard of before. I was chilled by the fact that she had killed hundreds of girls and women–stories say up to 650–and I found myself haunted by this. Who were all these silenced girls and women? I started to dig deeper, and found there was much written about Bathory, herself, but I couldn’t find anything that put her victims at the center of the narrative. Eventually I started to be haunted by their voices, a ghostly chorus of them–they visited me in a sort of waking dream–and knew I’d have to try to capture them on the page, maybe even bring them some much belated justice in the process.

What voices have you been dreaming lately?

ALV: My current novel in progress which has become a ‘magical realism’ journey, which includes Quetzalcoatl, a Mexican deity that’s both God/Goddess, female/male- I love that. I love her/his voice, I’m listening. In our email exchange you mentioned that writing these voices, these women and girls, came to you when you were pregnant, but the violence you would have to undertake and enter was too much while pregnant. I understand completely, as a once pregnant poet/writer. Our body, mind, spirit, is tuned to creation, not torture and murder. And so, when you finally were able to write these voices what was your experience of being inside their bodies, listening to their voices. As my Yaqui Mamacita used to say to me, “Tienes coraje, niña…You have courage, child.” Tienes coraje, Gayle- these voices coming through you, their spirit bodies.

GB: I am so excited to read your book in progress! *You* have so much courage, dear Alma–you inspire me unendingly. Thank you for all of your kind words.

And yes, I realized this was definitely not a healthy book for me to be writing while pregnant–I didn’t want the baby to absorb the agony of all the torture and murder I was reading and writing about, although sometimes I do wonder if my early foray into this book helped prepare me emotionally for my mom’s suicide one week after I gave birth. My creative energies shifted after her death–I needed to write about her, about our relationship; I needed to try to make sense of our past together and the brutal way she ended her life. The memoir that came out of this, The Art of Misdiagnosis, was the most necessary and difficult book I’d ever written, and when I was done with it, I felt so lost as a writer. I didn’t think it was possible to write anything that could ever feel as meaningful as the memoir had. Then these ghosts started to whisper to me again, so I decided to look at the early pages I had written, and got sucked right back into the project. It ultimately felt like the right book to throw myself into after my memoir–I was ready to step out of my own story into a grief bigger than my own (for somehow it felt right to continue to write about grief. And to continue to break silences. I had broken so many within me for my memoir, and this project was a chance to break historical silences).

Entering the experience of these girls and women was excruciating–it broke my heart and took my breath away again and again to not only learn what they endured, but to try to enter into their pain on the page (knowing what they endured is beyond anything I can comprehend with my own body, something I acknowledge within the book, when the ghosts tell the reader they won’t be able to comprehend the pain these girls and women experienced). These ghosts no longer have bodies, of course, but I imagined them still being able to access echoes of their physical trauma, as I write here:

“Your body remembers even when you no longer have a body

(some tender part of you still flinches)

(some immaterial nerves still flare)”

I should mention that Bathory’s story has been written about in a titillating way, and I didn’t want to do that, not in the least; I wanted to show the true human cost of the suffering she inflicted. I wanted to force us to confront the horror these girls and women faced, because I believe it’s important to look at inhumanity head on; If we don’t face it, it’s harder to stop it, to prevent it. And I want to use the book as a way to raise awareness of current horror–the devastating number of missing and murdered indigenous women–and to raise funds for organizations working to stop this present-day genocide.

ALV: I love the above quote, “Your body remembers even when you no longer have a body”…I think of the science based fact that our DNA memory/trauma is passed onto the family line, future human beings. These voices had that kind of alive echo for me; that their memories, traumas were being passed onto me, the reader, via their channel, you. Silenced no more; their spirits can now rest, move on to current lives, as in reincarnation, with joy (I hope). Writing these voices, their horrific experiences in the body, must have been a passing through the fire ritual for you as the channel, the writer. And after your mother’s suicide, the birth of your baby, the ritual of fire, that cleansing, so wise, and so hard. Yes, The Art of Misdiagnosis, your memoir, the relationship with your mother, an immense fire ritual, that cleansing.

In Santa Fe, New Mexico, there’s a yearly fire ritual, Zozobra, where a huge man figure is burned, wailing all the while. People bring divorce papers, painful letters, their own letters to pain and grief, and who knows what, to add to this fire. I imagined this man figure as The Patriarchy burning to dark ashes, all the pain from that centuries old false power structure. And in the Southwest the pain of native genocide is still felt strongly, and as you write the ongoing missing, murders, rapes of indigenous women. Those thousands of silent voices, their in the body experiences. The genocidal Femicide that continues globally; the millions of girls, women, boys trafficked globally. For those who are receptive, they come to us in dreams. I just included some in my novel in progress, and have a feeling they’re not done with me. As I also believe they aren’t done with you, amiga, gracias a la Diosa…the Goddess in all her guises.

And so, with the ritual of fire, that cleansing, in mind- what gifts did you receive in return as channel, writer and woman? *Again, I love your coraje, courage…

GB: Oh, thank you so much for sharing all of this–I loved hearing about the Zozobra ritual; your imagining of burning the Patriarchy to ash really hits home. May it be so! I’ve used fire to burn things that no longer serve me (and water to do the same, the Tashlich ritual of casting bread during the Jewish High Holy Days) and it’s always such a freeing ritual. This book definitely felt like a trial by fire, and did have a cleansing effect. It showed me I am stronger than I know, that I can face the world’s pain, give voice to the world’s pain, and still find joy on this beautiful, broken Earth. It helped me expand my creative envelope, which makes me want to keep stretching it, to keep finding new ways to approach my work. I agree–these silenced voices aren’t done with me yet, and I’m eager to see where they’ll take me. I envision this book being adapted into a theater piece–I love the idea of a real chorus giving voice to these ghosts–and have a few irons in the fire toward that end. We’ll see what happens! I would love to know more about the silenced voices entering your novel (and to reading them some day!)

ALV: A theatre piece of a chorus giving voice to these Spirits, wonderful. This makes me imagine them all in red (fire) costumes, speaking, witnessing their very brief lives- mostly girls from ten to fourteen, from what I’ve read. Which makes me wonder what Countess Bathory’s voice would sound like, say. Supposedly she had epilepsy as a young girl, with blood swiped on her lips, a cure. And she witnessed cruel punishments as a girl, the royal household. It makes me wonder what her girl voice would sound like, say. However, given the acutely alive voices of her victims, their horrific experiences flesh out the Countess vividly. And so, even briefly, to see/hear her voice as a girl here, for a moment. Briefly. I love that these voices expanded your creative envelope, to find new ways to approach your writing- exciting!

As I journey with my characters, this novel in progress, we keep listening to the silenced voices, as well as to the joyful, singing voices. That balance keeps me going- this is my first all out ‘magical realism’ journey, novel, so I’m constantly surprised.

GB: Surprise is one of my very favorite parts of the writing journey–I love that your novel in progress is offering up so much surprise for you!

Your question about Countess Bathory’s girl voice is such a profound one, and one I’m not sure how to answer. I knew I had to include her in this narrative to some extent, since her actions led to the current state of these ghosts, but of course I wanted to center the narrative on the lives she impacted, the lives she ended, not her (just as some journalists are trying to do in this era of mass shootings, focusing on stories of the victims of gun violence instead of their killers, to avoid giving notoriety to perpetrators of these horrific acts.) That said, she is certainly a compelling and complicated figure, and her childhood does fascinate me. I’m not sure I can access her voice at this point, though. It reminds me of when I started writing my memoir–I was so angry at my mom, it was hard to see her with compassion (and a large part of the journey of my memoir was coming to that place of compassion.) I think I’m still too angry at Countess Bathory to be able to see her clearly, and I think that comes through when the ghosts say “The Lady knew what it was like to leave home at a young age, sent to live with the Nádasdys at twelve so she could learn the ways of the estate before her wedding two years hence.//Does that give you sympathy for her? Have it if you must, have sympathy for poor, poor, Erzsébet Báthory (who had sympathy for none but herself).” I do have some glimmerings of compassion for her, though, and when I think of her girl voice, I really only hear two words: “Help me.” No one did.

ALV: “Help me.” Bathory’s girl voice. “No one did.” Your response says it all, Gayle- punched me in the gut, where truth often lands. And I can hear her small girl voice whisper, “Help me.” As so many girls whisper, shout if they have the chance- the millions of trafficked girls, and boys- who hears them. The voice, your answer, chillingly true. The hundreds of girls she passed her pain onto- the chorus of voices in your book. At last they are heard, and of course I love the idea of a real chorus of voices speaking for them. I imagine their spirits joining those throats, voices. What that space will feel like as they speak their truths. Powerful stuff.

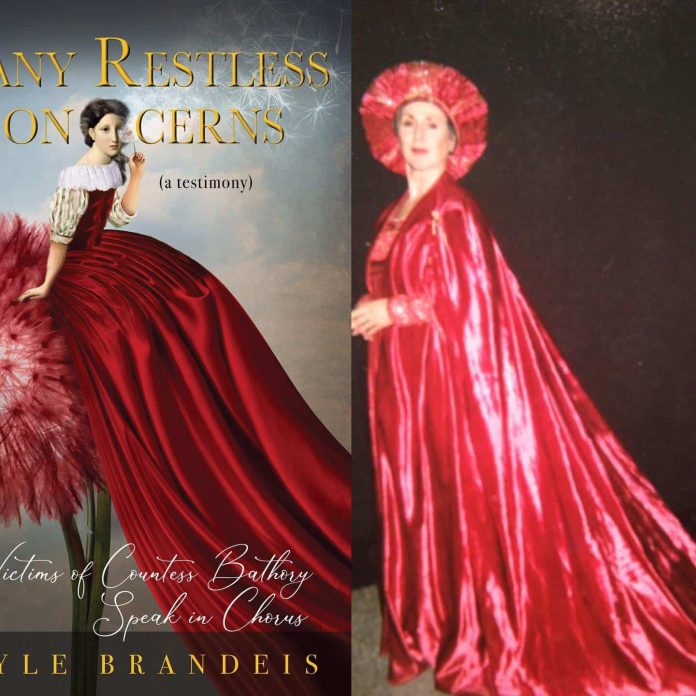

You speak of being angry with your mother; her suicide, your loss, your sorrow. As you felt anger with Countess Bathory; I felt waves of anger, and sorrow, reading the spirit’s alive voices. I’m wondering- do you imagine your mother taking part in the chorus of voices if she was still with us, now. I loved that photo of her in that stand in opera dress/costume, so magnificent. I can almost hear her- her body, her stance. I sense her intelligence, courage, strength in that stance. I also sense how proud of you she is, perhaps cheering you on page by page. I feel my Mamacita’s presence as I write- my joy, sorrow, rage, how it all transforms on the page. My body, every cell. Transformation. Your book, the voices, leads to this, transformation. Healing.

GB: So deeply grateful for your insight, your vision, dear Alma. I’ve had to sit with this question for a while, as you know. After my sister in law mentioned that the book cover reminded her of one of my mom’s opera photos, and I found the photo in question, I was blindsided by how similar the two are, how the red (a skirt in the cover, a cape in the photo of my mom) drapes in the exact same way to the lower right corner of each image. My breath stopped for a moment. I am still puzzling out the connection–both are powerful women who caused harm, although my mom did so on a much, much smaller scale; it’s likely I’ve made other subconscious connections between them, our stories, that I’ll need some time to excavate. But even so, yes, I do feel my mom’s pride in me–she was always so proud of me, even though I could feel her frustration with the fact that I was never as “successful” as she had wanted me to be–and I’m realizing in some ways, I’m carrying on the work she started. She wanted to give women voice, too. She started her organization, The National Organization for Financially Abused Women, to create a chorus of women’s voices to change divorce legislation (and even though the founding of it was based on the delusional belief that my father was hiding millions of dollars from her, the organization did real and important work in the world.) I think she would love to be part of the chorus of this book. I can hear and see her, too, dressed in red, lifting her voice with all her heart.

ALV: I simply love the final sentence of your response, “…lifting her voice with all her heart.” If you’ve made subconscious choices between your mother and Countess Bathory- the pain in your relationship, the pain of the voices you heard, brought to life on the page, what a strange gift of healing. And it seems all healing comes to us as a strange gift- nothing planned, nothing tidy. Healing comes to us with its own life force if/when we’re ready for transformation, to be healed, again. I imagine your mother’s presence in your imagination, body, memories, will always bring you strange gifts; as Mamacita’s presence has for me for sixty-three years.

I am so honored to have this exchange with you, amiga- our first exchange as student-teacher twenty years ago. I immediately saw your brilliance as I read your first novel, The Book of Dead Birds, which has since, of course, been published with so many deserved awards. Then we became friends, and then colleagues as you began teaching in the same MFA in creative writing program. How I loved seeing your shining face of light at our opening faculty meeting- how I loved our deep talks at our traditional Thursday night dinners, with piña coladas. And our humor together- graduation day, so many amazing writers, poets graduating. As we stood in line in our faculty graduation robes, we began to feel a bit wacky, threatening to do The Worm. Right there in our robes. I was crying with laughter, as you were. I love the ecstatic energy you carry and share, from your own being, to your writing. And so, to say it publicly, how grateful I am to know you, and always to read your work, all genres.

Okay, one more question- a brief answer will do. In Bali I walked into a courtyard with an immense eagle perched on steel, tethered by its leg/talon. A woman shaman, healer, walked out to greet me- I asked why the eagle wasn’t free. She asked me, “What is freedom, madam?” Over the years I’ve answered this question in many ways; there’s so many answers, of course. I would love to hear yours, even a sentence.

Mucho amor, amiga, milagros y piña coladas. And The Worm, always.

GB: I’m so honored and grateful to know you, too, my dear Alma, to have this conversation with you. What a gift. Whenever I see an eagle, I think of this question that was posed to you in Bali–in fact, it pops into my head quite often. And yes, there are so many answers, but what speaks to me right now is the very first poem I ever wrote when I was four years old, a poem called “Little Wind” that went “Blow, little wind/blow the trees, little wind/blow the seas, little wind/blow me until I am free, little wind.” I think I somehow knew even then that creativity can be like a wind that blows through us, that makes us free, and to this day, I never feel more free than when I allow that wind to blow through me, when I get out of my own way and allow the poem or story or essay or dance to barrel through, not worrying about how it will be received in the world, just giving it the space to roar.

Thank you again, amazing Alma. You have helped me be more free through your mentorship, your example, and I’m forever grateful for your presence in my life, your presence in the world. Thank you from the bottom of my heart.

Order Alma Luz Villaneuva’s work here.

Order Gayle Brandeis’ work here, including her latest Many Restless Concerns, The Victims of Countess Bathory Speak in Chorus.

Upcoming events with Jen

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THE ALEKSANDER SCHOLARSHIP FUND