By Laraine Herring

My mother could have remained in Bay Ridge, taking the R train into Lower Manhattan to work at the Stock Exchange. She could have not met my father, who could have passed Spanish at Wake Forest and graduated there instead of transferring to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where they did not require two years of Spanish for a History major, where he did meet my mother, who was the first female accepted into the graduate school of mathematics at Chapel Hill, at an uncharacteristic football game where she’d gone with her roommate as an out for her blind date. But if she had remained working at the Stock Exchange riding the R train this would not have happened.

My father would have married a woman named Betty, not Elinor. I’m reasonably confident of this because when he died we found drawings Betty had made for him of his face, his golf swing, his eyes, and she called the house a lot and tried to make friends with my mother. She stopped calling once we moved from North Carolina to Arizona, but I still have one of the pictures she drew in a box in my closet. She could have been my mother, but there’s a reasonable chance she is dead now, or at the very least married to someone who never quite measured up to my father, but who nonetheless was a decent man. Betty could be writing this piece too. She would start with: I might have married Glenn…and I don’t know what she would have written next because I don’t know her. But I have her picture.

My father could have died with the polio in 1949 like he was supposed to. Like everyone did. Like the boy who was in the iron lung next to his who died in the night, my father talking to him in the dark, not realizing he had gone. The boy’s name was Charlie, and the two times my father spoke of him, he trailed off into ellipses.

Charlie could have lived like my father lived. He could have broken out of the iron lung and not imprinted my father with his death in the night. It is hard for a boy of eight to carry the death of a boy of seven in the dark. That’s a weight that lingers, like the bitter of chocolate.

My father could have died in 1976 after his heart attack like he was supposed to. Like the doctors said he would. Like maybe he would have, except one round of doctors had already told him in 1949 he should have died and he told them he was not going to die and so he had a script for what to do the next time he heard that.

I could have died in 2017 of colon cancer, but I didn’t. I knew how to tell the doctors no because my father told them no twice. Even when he died, he told them no. He pulled out his tubes in unconscious urgency. He clawed at his oxygen. It was his time for dying, and he was telling them no to the saving.

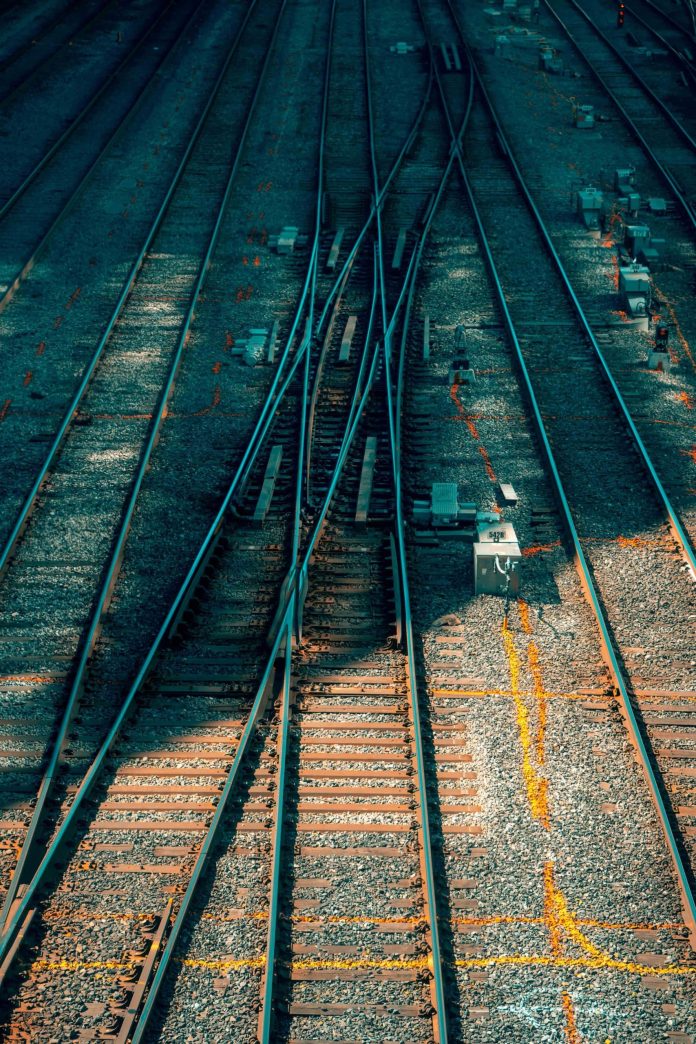

If my father hadn’t died in 1987, I would have gone to Oregon. I had a scholarship to William and Mary and I was desperate to get out of the desert and into the green. But I graduated from high school in 1986 and I knew I couldn’t go because my father was dying and so I didn’t go, but every time I visit the Northwest I see my shadow in the train and I see a possible life where I wouldn’t have met my husband, who is a born and bred Northern Arizona man, a man who becomes sad in the rain. Too much sun makes me sad, but not my husband, and somewhere between 1986 and now I realized that every choice I make may not give me everything I want. Every choice is many choices. I can visit the trees and the water and the damp, but I slept with many wrong people before I met my husband and I know what right feels like now, even if it’s in the desert.

If I hadn’t lived with the abuser in 1988 after my father died, I wouldn’t have had my heart smashed open to an empathy I didn’t know was possible. Or I might have died there. Other women do. I walked out of their graveyard.

If my father’s family had not been Southern Baptist we might have remained in the will and could be living in North Carolina by the Atlantic in the family home. We could have an altar of sand dollars on the dining table, gathered over years of morning walks at low tide. I might wear navy and forgo white after Labor Day and know how to can peaches. But probably not.

If I had stayed in Phoenix in 2003 instead of moving to Prescott—I had to get out of the haunting heat-sun—I wouldn’t have met my husband. I left Phoenix because a tree fell on my house and then I had a dream that echoed the dream I had when we first moved to Phoenix in 1981—I will die in this place if I don’t leave—and so I was gone in a month. This is the only time in my life I made a decision of that magnitude so quickly.

That’s not true. I told the oncologist I would not do chemotherapy and radiation even quicker. They pushed it like a desperate realtor hawking swampland in Florida but I said no. I come from a long line of people who told the doctors no. They were exasperated and fired me as a patient. This was OK because I am not patient.

If I hadn’t told my doctors no, I wouldn’t have met the psychic in Encinitas the year after my surgery who handed me a rose quartz and looked me straight like only the real psychics can do and said, “It must have been so hard for you to fight for your body’s intuition.” And I cried in the middle of the psychic fair, watching the Pacific breeze blowing her psychedelic psychic skirt around her legs. She was the first person to recognize that—the first person to let me recognize that—yes, yes, I had to fight to say no. I had to fight. The wrong choice was easier. The wrong choice was covered by insurance. My wrong choices—every single one of them—were the easier decisions. The ones that cost me my voice.

“I didn’t know how hard it would be,” I told her. Harder than cancer. Harder than surgery. The refusal to walk the pre-written cancer-journey-story filleted me. “If I did chemo, I would die,” I said. And she held my hands and let me cry and the ocean carried my salt away like she always does.

If my mother had stayed in Bay Ridge riding the R train, I wouldn’t be with her today, riding the R train, returning to Bay Ridge to eat pizza at Lucas, which is now the Brooklyn Firefly, because it was where they went for pizza when she was a girl, back when she wasn’t allowed in the special math and science high school because it was only for boys, back when my father was learning how to walk again and Betty was drawing his picture and I was waiting somewhere velvet-dark until I found the woman who was strong enough to bear all of me.

Upcoming events with Jen

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

THE ALEKSANDER SCHOLARSHIP FUND