by Barbara Krasner

An elderly man in a plaid shirt and dark-rimmed glasses walked up to me after the meeting of the Museum Committee. He said, “I knew your grandparents. I went to their store all the time for ham sandwiches.”

“Are you sure?” I asked.

He had to be wrong. Max and Eva Krasner would never touch ham, let alone serve it. Maybe a helper in the store did it for them, although the helpers would have been my father and his brothers.

The man broadened his smile, likely recalling the taste of the sandwich. “Your grandmother was Eva, right?”

“Yes, I never knew her though. She died years before I was born.”

Maybe it was the ham that did it. Eva Zuckerkandel Krasner was the daughter of a kosher butcher. This man’s memory was playing tricks. Maybe he got his sandwiches somewhere else in the neighborhood. But as our conversation continued, he said he crossed Ridge Road from Queen of Peace Roman Catholic Church to my grandparents’ general store in North Arlington. Publicly, I had to accept the compliment that my grandmother made a great piggy sandwich, but privately, I was plagued by the question: Why would a kosher butcher’s daughter comply with such a treyf (non-kosher) request?

To answer the question, I started with what I already knew. In 1920, my grandparents moved northeast across the Passaic River from their flat on Van Buren Street in bustling Newark to a lot at the intersection of Ridge Road and Sunset Avenue in North Arlington, where a sewerage system had not yet been introduced. Perhaps Max and Eva thought this dorf resembled a shtetl. For Max that meant a village near Minsk and for Eva that meant her hamlet in the southeast corner of Austria-Hungary known as Galicia. Max immigrated to Newark in 1899 and eventually set himself up as a grocer. It was as a grocer he chose to present his best self (while he still had hair) on a matchmaker’s post card. Eva immigrated to New York City in 1913 and somehow was introduced to Max. She had other suitors, but Max had a business, a store. This she found attractive, and why not? She was a kosher butcher’s daughter, the eldest child.

In 1920, Max and Eva, along with their one-year old (my father), settled into their corner lot. They had an apartment behind the store front. They numbered among the very few Jewish families here at the confluence of Bergen and Hudson counties and midway between Newark and Jersey City. My grandmother, who had a head for business, must have figured their general store could make a buck in this burgeoning burg, what with the store on the main street and rentable apartments above the store.

In 1920, the cornerstone to Queen of Peace was laid on Ridge Road at the intersection with Sunset Avenue. Max and Eva would have looked out their store front windows to see stacks of lumber and bricks piled up on mounds of dirt just waiting for cranes to put these materials and the spire in place. In 1925 the church’s grammar school opened. The high school saw its first graduates in 1934.

My grandmother laid out a pot of something to simmer on the stove for my father—and later my two uncles and aunt. Eva would only cook kosher food—hot dogs, stews, soups—on the private family residence side of the door that separated it from the store. But as the Krasner kids ate their kosher meats bought from Prince Street in Newark’s Third District, the Queen of Peace kids popped across the street to get sandwiches. Ham sandwiches.

A kosher butcher’s daughter making ham sandwiches. I imagine she washed her hands constantly to make sure she minimized contact with treyf. I also imagine she thought it was a necessary sacrifice she had to make for the business. Catholic customers want ham, and kids’ money came from the parents, and if the kids were satisfied, the parents might patronize the store more. Generally, my grandfather ran the grocery and my grandmother ran dry goods. Making ham sandwiches had to be a shrewd business decision. I am guessing the sandwiches were made with white bread, certainly not on Jewish rye. I’m also guessing my grandmother would have a “ham” knife and “ham” slicer. There would be milchadik (dairy) utensils, fleyshadik (meat) utensils, and treyf utensils. She would never intentionally violate the traditions. No, ham was business and it’s not like she herself was eating it. What one does at home was sacred. What one does in a public space was something else.

There could be no question that the proximity of this large church and the volume of parishioners had to be taken into consideration in my grandparents’ business. My father had always intimated that the church ran the town, especially when it turned down his request for a parking lot and he was forced out of a twenty-year supermarket business because he could no longer compete.

Ham sandwiches began to make sense, practical dollars and cents. By making ham sandwiches, Eva Krasner showed she could be counted on in the community. She was one of them—a North Arlingtonian, not a Jewish immigrant outcast. She spoke English as did Max with barely a trace of an accent, I’d been told.

A Jew who would make ham sandwiches protected herself against antisemitism and stuck to her vision of buying land throughout the area.

A Jew who would make ham sandwiches eased the way for her kids to make friends outside the tribe.

A kosher butcher’s daughter who made ham sandwiches knew how diplomacy worked. She knew the way of the world.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

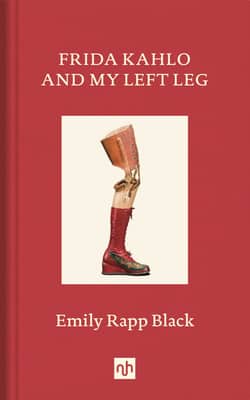

You know it’s an amazing year to be a reader when Emily Rapp Black has another book coming. Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg is remarkable. In this book, Emily gives us a look into how Frida Kahlo influenced her own understanding of what it means to be creative and to be disabled. Like much of her writing, this book also gives us a look into moving on (or passed or through) when it feels like everything is gone.

Pick up a copy at Bookshop.org or Amazon and let us know what you think!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Are you ready to take your writing to the next level?

Two of our favorite writing resources are launching new opportunities for working on your craft. Circe Consulting was formed when Emily Rapp Black and Gina Frangello decided to collaborate on a writing space. Corporeal Writing is under the direction of Lidia Yuknavitch. Both believe in the importance of listening to the stories your body tells. If you sign up for a course, tell them The ManifestStation sent you!

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~