by Larkin Warren

Eight of us were wed that summer of 1981. Each of the four engagements had come about during the previous bone-crackingly cold New Hampshire winter, although I’d like to believe that all the troth-pledging was more about love and joy than the need for warmth in icy weather.

We lived then in a university community, where marriage itself was subject to flinty-eyed skepticism—three of us eight to-be-marrieds were divorced, with kids in tow and wedding albums long lost in an attic or cellar. Nevertheless, as mud season passed and the lilacs appeared, we all prepared to take a plunge that seemed to grow ever more traditional as the days went by. Gathering on weekends, we ate pints of strawberries, pounds of brie, drank more Champagne than was customary on a teacher’s salary, agonized over venues and budgets, and complained, of course, about our parents—because what’s a march towards a wedding without that?

Coincidentally, another couple, first-timers both, planned a similar event. Prince Charles and Lady Diana’s wedding would be larger, certainly, than all four of ours combined; her engagement ring big as a Volkswagon headlight, the invitation list and seating chart more complicated than the annual gathering of the UN General Assembly. We guessed that Diana’s and Charles’ whole coping-with-the-parents thing resembled rolling a large power mower over a hornets’ nest. We tried to envision the monogrammed thank-you notes, the writer’s cramp. “Ha!” somebody grumped. “Not likely she’s writing them herself!”

Whether Royalists, Fenians, or flat-out cynics, we refused to begrudge them the royal circus and the related hoopla. We were all determined not to be cynical that summer. They were in love, we were in love—and when you’re sufficiently love-addled, Frank Sinatra is forever crooning in the background, every sunset is peach perfection, and it’s an easy if somewhat wacky leap to emotional kinship with the future King and Queen of England.

By the day of the royal wedding, our own four weddings had been achieved. All our kids were in embarrassment recovery and all the wedding-cake tops (two organic from a local farm store, one eight-layered from a fancy caterer, one Mom-made) were stashed in fridge freezers, to be thawed and eaten at the first anniversaries. And so it was that on July 29, each new married couple, bleary-eyed and feeling more than a little sheepish, rose at dawn, fired up the coffee and joined teams of gushing TV network anchors and the billion other guests at the Spencer/Windsor wedding.

Feminism, pragmatism, and reality checks notwithstanding, it was difficult at first not to think in fairy tale terms as the veiled girl, swathed in an acre of virginal silk, arrived in the golden coach, glanced shyly up at her prince, and Bach rang throughout the cathedral; we were, after all, the first generation of Disney-movie kids, brought up on princes, princesses, and happily ever after, even if Ms magazine and Our Bodies Ourselves sat on the bookshelf next to a Virginia Woolf novel and somebody’s dissertation on the various psychoses in Grimms’ fairy tales.

It did occur to me, however, that if we dropped a nickel into the piggy bank every time a commentator actually used the words “fairy tale,” we might make a sizable dent in my son’s tuition savings account. “Why doesn’t he just grab her and kiss her?” asked said son with a medium measure of disgust, having witnessed many other silly grownups do precisely that for weeks.

A month or so later, my husband’s parents returned from a vacation trip to the UK with gold-trimmed souvenir royal wedding cups, one for my sister-in-law, one for me. I kept mine on the kitchen counter for a while, ceremoniously using it whenever I drank tea, silently begging forgiveness of my paternal grandmother, who’d secretly funneled her pension money to the Irish Republican Army. My sister-in-law used hers briefly as well, then stowed it away for safety after her two kids were born.

By the time little princes Wills and Harry were making shiny appearances in People magazine, our Summer of ‘81 group numbered three babies, two divorces, a few rounds of infertility treatments and a couple of complicated midlife career adjustments. At that point—pre-internet, pre-social media, pre-cell-phone cams in every hand around the world—we didn’t know about the mistress, the affairs, the drama worthy of Bizet’s Carmen. We didn’t know that Diana had flung herself down a flight of stairs in a bid for Charles’ attention, although one or two of us might’ve understood. I surveyed my own castle—eggy dishes in the sink, two dogs who ate shoes as if they were kibble, the husband who worked all hours, and the moody adolescent who painted Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon album cover on his bedroom wall—the entire bedroom wall. “A lady in waiting would be nice,” I muttered.

Time kept passing. Parents aged and died. Kids grew up, friends moved away. Somebody’s son flunked out of college, another joined the Navy, a daughter eloped. Soon, we were all linked only by Christmas cards with ever-changing zip codes. Somewhere in there, the UK fairytale went all to hell.

On the last day of August 1997, the Princess of Wales and two others in her car died in an automobile crash whose grisliness was surpassed only by its agonizing stupidity: the drunk limo driver, the frenzied pack of paparazzi, the dying woman pinned like a butterfly in a shadow box.

A week later, I once again rose at dawn, heading for the television and feeling grim. For breakfast, I ate an entire box of Peek Frean lemon biscuits (with the “by Royal appointment” seal on the box), and drank Earl Grey in the gold-trimmed wedding cup. I don’t even like Earl Grey, and I had no doubt my IRA Granny spun in her grave. There again was the cathedral and the soaring music. Some of the faces were recognizable, all of them were older. “I thought I’d feel like an idiot watching this,” said my husband, who joined my vigil late and under protest. “But I don’t. I’m actually sad.” We both agreed that Sir Elton John could’ve used a couple of second thoughts.

That afternoon, my sister-in-law called, tired and teary. “I stumbled all over the place in the cellar this morning,” she said, “hunting for that damn teacup. Scraped my shins on every toy my kids have ever owned.”

I told her about her brother’s unexpected sadness, about my lemon-biscuit breakfast. We tried to figure out what it was that we were feeling, why someone and something that had absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with us seemed, suddenly, to have everything to do with us. For her, a mother of very young children, it was the unimaginable sorrow of two boys walking behind their mother’s coffin. For me, it seemed somehow about the sun-burnished wedding summer, the strawberries and champagne, the blind hope and optimism, and the friends whose lives and loves we had shared. We’d made promises. Mostly, we’d kept them “The odd thing is, I think I feel grateful,” I said.

“Me, too,” she said. “For the junk in the cellar. The dirty laundry. Even the old Barney videos.”

How often, in the frayed ribbon of a lifetime, do lovers and friends, husbands and wives, parents and kids, do wrong, disappoint, betray, yet somehow manage to start over? What’s the score now, as we pass another anniversary and roll however clumsily towards the next? My son, when he was little, had a term for the number of stars in the sky: “infinity many.”

“Most of all,” said my sister-in-law that long ago morning, in a very soft voice, “I’m just thankful for my completely ordinary life.”

Larkin Warren lives in northern NH. She has collaborated on six-and-a-half memoirs, is writing one of her own, and her poetry’s been published in Mississpipi Review, Ohio Review, Yankee magazine, Slow Motion Review (NYU), Quarterly West and others, She is currently owned by a mini Aussie shepherd rescued from a NYC kill shelter. Her poetry chapbook, Old Sheets, was published by Alice James books (Farmington, Maine) in the previous century. Her essays have appeared in New York Times magazine, NYTimes op-ed page, AARP magazine, Esquire, Good Housekeeping, Glamour, Salon, and others.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

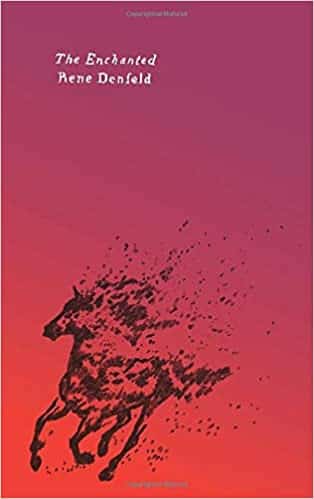

Margaret Attwood swooned over The Child Finder and The Butterfly Girl, but Enchanted is the novel that we keep going back to. The world of Enchanted is magical, mysterious, and perilous. The place itself is an old stone prison and the story is raw and beautiful. We are big fans of Rene Denfeld. Her advocacy and her creativity are inspiring. Check out our Rene Denfeld Archive.

Order the book from Amazon or Bookshop.org

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~