The afternoon I returned home from taking Paul to college, I stepped out of the car and stretched my creaking limbs with a groan. After seven hours of travelling, I felt at least a hundred and six years old, and even though Paul had done the driving up to school, we had been crammed into the front seat with the entirety of his belongings filling up the rest of the car, leaving not a molecule of daylight. I took stock of the dry grass, and hesitated before climbing the three stairs to the front door. There was a stranger in the house – Paul’s absence – and I was not yet ready to confront it. To my left, I saw what appeared to be a pile of mud on the ground in front of the kitchen window. Late August heat seared my bare shoulders as I walked across the strip of lawn to investigate. Sunscreen had been the last thing on my mind at 6 am that morning, as I packed my son, with his bedding, photographs, and a garbage bag full of sneakers, into my car to move him away from home forever.

Year after year, robins built their nest in the juniper tree which stood dead center in front of the house, and which was growing so tall it seemed to bisect the structure into two distinct halves. When I went downstairs each morning to start my coffee, and the kitchen window had been left open overnight, I startled the birds and they in turn startled me with a flapping noise that was always unsettling for a moment, so close was it to my ears.

I did not remember the night before as distinctly windy, though I had lain awake, trying not to focus on the enormity of the day ahead. My boy was leaving for college. He’s ready, and so am I. In two more years, it would be Kelly’s turn. I needed to wake up in six hours, now four, now two. But at some point, something had unmoored the nest from its perch, and there it was, flipped onto the strip of lawn, slightly flattened due to its tumble to earth. Shards of eggshell were scattered in a small radius on the undergrowth but one unscathed egg sat close by in sky-blue perfection, balanced on a myrtle leaf. I turned over the nest, whose center basket retained its curve, and patted down the grass and mud on the underside. I put the egg inside, and rested the whole apparatus on the top step by the door, in the corner.

I regarded this archaeological finding as more than a little absurd, and laughed out loud. It could be that the fallen nest had been there for weeks but in the last month, I had barely looked up, so focused was I on getting Paul ready, on my new responsibilities at the hospital, and on Kelly’s breakup with the wealthy boy from Ames. There was no way of knowing; some signs can only be read by the willing.

During the year that my husband Dan thought about leaving me, and then finally did, the disturbance honed my senses and I became superstitious. Not about ladders or black cats, although I did avoid the panther cage when I accompanied Paul’s sixth grade class to the zoo. Rather, I assigned power to whatever was littered in my path, as if my surroundings offered a puzzle of encoded messages, and none of the pieces could be ignored.

I believed that a dried leaf that floated around my feet nudged me with a message (decay is also beautiful?), or that my grandmother’s topaz that sat in my jewelry case suddenly caught the light and my eye, with ancestral wisdom I had to decipher. I began to collect charms which I wore on a chain around my neck. A seahorse, which only swims forward; a sun, which glows behind rainclouds, the cross from my baptism, to remind me of the child I had once been. But despite my attempts at sorcery, soon Dan moved in with Laura, a grad student in town, whom he loved as much as he had loved me when I, too, was twenty six. The talismans that dangled around my neck seemed like pathetic attempts at optimism. So, I removed them, and everything became what they had been before: A dead leaf, a rock in a box, a bunch of gold charms.

My son had been gone for exactly eight hours but my house was already changed. The emptiness consumed the quiet rooms, which seemed to honor Paul’s departure by manifesting a respectful stillness. Baxter, our mutt, did not spring up to me in his usual way, but rather took his time, loped towards me, not wanting to seem too cheerful in case I was in a state of full-on despair. I slipped the sandals off my feet and joined him on the kitchen floor.

“Bax, Bax, Bax,” I said. “You okay, boy? ‘Cos I am.”

I ran my fingers along his neck and curved around, scratching vigorously around his ears. I had dreaded getting this dog, a blatant attempt to buy my children’s happiness after the divorce. But like any adopted baby, I fell hard for him, and could not imagine life without his good cheer and even keel. It was Baxter who pitched our family into balance, and sometimes I believed he was a better, more capable, and certainly more patient parent than I.

I rested my forearm, and then my head, on his side. “You know, it was time.” I stood up, still stroking his fur. “You’re getting gray around the edges, my friend,” I said. “Welcome to the club.”

There was a note on the counter from Kelly. Mom, I’m doing the 7-3 today. Tom wants to see me (!!!). Call me! Love, K.

It pained me to think that after her summer of heartbreak, she would run back to Tom as soon as he beckoned. He was a junior who lived a half an hour away, and he had succumbed, cruelly, to the charms of another girl in June. It had been tortuous for me, as I felt somewhat responsible for their romance in the first place. Tom’s father was an orthopedic surgeon in the hospital where I taught nursing. I had taken Kelly to the university Christmas party last year in lieu of Keith, the man who had been squiring me around but was not much up for the office holiday bash.

She had worn a black camisole dress with rhinestone spaghetti straps, and silver heels she bought online. I marveled at the ease with which my daughter glided across the room, not to mention the salt-covered, ice-slicked parking lot. Tom noticed her, of course, and they got together a few weeks later on New Year’s Eve. I did not care for his father, who still swaggered like the star quarterback, and was known to have skillful hands and an eye for my students, but not much of a healing demeanor. It should not have colored my feelings for the son.

I picked up the phone and dialed Kelly at Bank Street Grill, where she was a waitress. She would be nearing the end of her shift, dead on her feet, wavy hair beginning to unravel from her clip, still smiling at customers.

“Hi sweetie,” I said. “Long day?”

“Totally. We’ve been really busy. Did you get Paul settled?”

“Yes. Alex was there, his roommate. He seems great. They have a kitchen.”

“Are you sad, Mom?”

“Don’t worry about me, Kel. He’s ready and that’s what counts.”

“We’ll see him in a few weeks, right?”

“Very soon. Honey…Tom?”

“I know, I know. But I’m excited.”

“You’ve been great lately.”

“Don’t worry, Mom. Gotta go. I’ll see you in an hour. Love you!”

Don’t worry? I held her like a baby for hours this summer, felt her hair soak my fingertips from the heat and exertion of her sobs. For days, she had not left the house, despite platoons of ponytailed friends and soccer teammates who came by on bikes and in cars to get her back into the sunshine. Despite my promising her a hundred times that her heart was still whole. That no boy, or man, or person, could rob her of her soul and that it, too, was intact.

I poured coffee from the pitcher in the refrigerator, splashed in a drop of milk, and grabbed ice cubes from the freezer. Water condensed quickly around the glass and I gripped it as if it could steady me from what might be imminent in Paul’s room. The familiar faces on the wall greeted me. Usain Bolt, the 1998 Bulls. Inside the closet, I gazed at the empty space. I sat on the bed and remembered assembling it from printed instructions, learning the finer points of an Allen key screwdriver, shocking even myself with my ability to do things without Dan.

My brain scanned my body for sadness and regret, but it came back blank. For months, people began to treat Paul’s leaving as if it were his and my simultaneous demise. But I felt great satisfaction at raising a good man. I also felt one step closer to my own release. My friends and I – parents I’ve known since Paul started kindergarten, from the auction committee and the Little League candy bar drive – all found ourselves in the place that every mother and father does eventually, with kids moving away and for the most part, trying to prove they no longer needed us. It was sad, yes; tragic, no. We had worked hard and prepared them well. We, too, would be released.

I hesitated and looked blankly around the room. The ceramic mug he made when he was three or four still sat on the desk which was otherwise cleared of his entire schoolboy history. He had not packed it, and although it did not much surprise me that a college freshman would not be sentimental about a pre-school clay project, I was nevertheless surprised to see it left behind. I had thrown it away once, long ago, after the handle cracked off. Paul had dug it out of the trash, and brandished it before me, shedding angry tears, crying, “This is my CUP!”

I rose to pick it up, felt its smooth painted yellow sides, rough at the broken points, and looked inside. There was a pen cap, some paper clips, a blue cloth patch of some sort and a small bright orange shell. I removed it and wiped off the dust with the pad of my thumb. It was about the size of a nickel, unscarred and whole. A living thing had inhabited this shell in some far-flung sea. Then it floated to shore and was plucked off the sand by a boy. We were landlocked by over a thousand miles, had been to a half dozen beaches over the years, but I had no idea where it came from. I stuck it in my pocket.

I walked out and towards the bedroom, and gazed at the pile of books that sat, ever waiting for me, punishing but welcoming just the same. Now, I might have time for them. I looked up at the shelves stacked high with novels that held not only their own stories but the ancillary ones: where I was in my life on this earth when I read them. There were books from my honeymoon, and ones I had plowed through when I was on bed rest while pregnant with Kelly. Books that I read, or tried to, when I worked overnights as a young nurse, my eyes lacquered with fatigue. Others I had carried through airports, on vacation with the kids.

I picked one up and shuffled quickly through the pages, as if the smell of coffee and black tobacco would float towards me again, as it had while I read it in a cafe in Paris. I took myself there the first summer after our divorce when I had to give up my children to their father for two weeks. I recalled the agony, the bewilderment, the pointlessness of my attempt at escape. The stub of my boarding pass floated to the floor and I retrieved it: Carolyn Schepis, seat 46B. I stuck it back between the pages and as I reshelved the book, I heard the squeak of the front door.

It was Keith, whom I referred to at times as my boyfriend. He had begun to make noises about moving in together but as much as I liked sharing a bed with him when I was in the mood, the idea of committing to his laundry and general caretaking gave me the sensation of a hand gripping my throat. He too was divorced, and we had been together, or something like it, for a year.

“Carolyn?” he called. Always a question.

“Up here Keith,” I replied as I headed for the stairs, still barefoot. Keith stood in the foyer, holding forth a bag that looked like lunch, and when he saw me, he shut the door behind him. As he did, a mass of sticky heat from outdoors lumbered into the house, dissipating quickly in the air conditioning. He was in his coaching clothes, shorts, a gray T-shirt, fresh from pre-season practice with his high school soccer team. His smile betrayed more than a drop of sympathy which I tried to ignore by beaming back to him, widening my eyes gratefully at the appearance of both him, and food.

“I’m just seeing if you’re okay,” he said, wrapping a moist arm around me, and kissing me fully on the lips.

“You’re so sweet.” I continued, “Everyone keeps asking me that. I think I’m not supposed to be.” I looked in the bag. Chips. Good. “But I’m okay.”

“Where’d you find the nest?” Keith asked.

“Out front,” I said.

“Can I at least take you to dinner tonight?” Keith asked. “To celebrate? Or not…”

“Can I let you know?” I replied, grimacing. “I’m pretty tired. Kelly’s getting back together with Tom.”

“She’ll have to learn somehow,” said Keith. “Let me pick you up at 6.”

“Come by at 7. Now, I need a nap. And a shower.”

“Do you need company?” he asked, “’Cos I could use some.”

“Nice try,” I answered. Ridiculous to think I would be in the mood, and he knew it.

“I’m kidding,” Keith said, sheepishly.

“You are not,” I said. “See you later. Thanks for the lunch. I don’t deserve you.”

“No,” he said, “You don’t. But I keep hoping you will.”

I closed the door behind Keith and in the kitchen, opened the bag of potato chips. It was cool inside the house, and in my tank top, I almost needed a sweater. I chewed on half of the ham sandwich, with mustard only, just how I liked it, and left the second half uneaten. I went upstairs and while getting undressed, I noticed gold tips on the leaves of the sugar maples that lined the back fence. Late August always seemed incongruous, how the trees just knew their time for turning, as if on cue.

After my shower, I heard Kelly come inside.

“Mom!” she cried. “That nest! You know it’s good luck to find a robin’s nest with whole eggs?”

She walked into my room as I was buttoning up my jeans.

“You should bring it inside,” she said excitedly.

“I’ll leave it out on the porch for now,” I said. “I’ll call Flanders, maybe they can pick it up or tell me what to do.” The nature center was a mile away, and could probably offer some quick advice.

“Yeah, you’re probably right.” She plunked down on my bed and curled up like a tired, satisfied kitten. “Do you have any laundry?” she asked. “I need to wash my restaurant shirt for tomorrow.”

“Sure, honey,” I answered, gathering my dirty clothes from the morning, and stopping to kiss her on the cheek as if she were a napping baby. “I’m doing a load now. Bring it downstairs.”

After she dressed for her reunion with Tom, I met her in the kitchen. She was fresh, her cheeks were lightly shimmered. She had done battle with her thick curls for years, had attacked them with all manner of flattening iron, conditioning salve and straightening paste. My hair is thin and barely holds a wave, and so I genuinely envied her mane, even though saying so had me branded as patronizing and, as her mother, I had no credibility anyway. Lately, though she seemed to have embraced her wild hairstyle, which was distinct in our flaxen-blonde town.

“I wish you wouldn’t,” I said.

“Mom,” she groaned. “He said he was sorry.”

“But he cheated on you, Kelly. You can’t get in the habit of thinking that’s okay,” I insisted.

“He made a mistake. We all do.” Kelly took a can of seltzer from the refrigerator and plunked it on the counter in front of me, popping it open with the aplomb of a veteran bartender.

I wanted to add, “And his father is such a creep,” but I held my tongue, knowing that it would be unfair to pass such judgment onto his son. It was, in fact, awkward to see Tom’s father in the hospital corridors, and I assumed he was doing perpetual reconnaissance on the fledgling nurses, especially the petite, busty ones. I felt sorry for his wife.

“Mom, you just hate men,” Kelly said, matter-of-fact.

“Kelly! I don’t either,” I said, recoiling somewhat from the sharp sting of her words. “What a horrible thing to say!” We fought rarely, and when we did, it wore me out for days. I scrambled for a reply. “You don’t deserve a cheater.”

“I’m sixteen, Mom,” Kelly exclaimed, hands extended before her, palms upturned. She looked at me and gulped from the soda can. “Not forty-four. Which should be considered young, but which you have redefined as “Time to give up.”

“Kelly,” I said limply.

“Look at how you treat Keith,” said Kelly. “Why do you even bother?”

“That’s really none of your business.” The unspoken words soured in my mouth. I cursed the rulebook that I wanted to tear up again and again, the one where it says a spurned spouse is not allowed to disparage the ex—ever, under any circumstances—to the children.

“Mom, so my heart broke. And we’re getting back together. It’s good and I’m happy.” I stared at her and she continued, “He screwed up. Who doesn’t?”

“It doesn’t mean you have to be waiting at the bus stop as soon as he wants to see you…” I began to feel something close to embarrassment, so I stopped.

“I’ll be home by 12. Promise. I have to be at work at 6 in the morning.” Kelly leaned over and pecked me on the forehead, and I stood to walk her to the door. Confidence lightened her bearing, it was impossible not to see that. “Don’t forget to put my uniform in the dryer! Thanks, Mom!”

My daughter disappeared into the early evening sun, which pooled on the walkway between the hedges. Above it, a wall of heat and light formed, thick and blinding.

Keith picked me up for dinner in town, and afterwards, I promised my favors for some other time. As we said goodnight, I asked him about Kelly’s accusation – there was no other word for it. I was not angry, but rather mystified.

“You don’t think I hate men, do you?” I asked. Moths congregated with loud flapping all around the porch light. One sat large and still on the door, a deep celadon green.

“Why do you ask that?” he said, tucking a lock of hair behind my ear, twirling it for a second around his finger.

“Kelly said that,” I answered.

Keith took a deep breath. “She’s a preternaturally wise young lady.”

“Uh-oh,” I said.

“You don’t hate men,” Keith said. “You just don’t like that most of them love women and have no idea how to do that right.”

“That’s absurd,” I protested.

“That’s the truth,” he said, kissing me again. “Now hurry up inside.”

I undressed in the dark, listening for a noise, any noise. I went to Paul’s room, and lay across his bed in my summer night gown, grasping the still-strong scent of a teenage boy. I stared at the ceiling while tears flowed straight down my cheeks, pooled around my ears, soaked my neck and eventually the pillowcase under my head.

Around midnight, I heard Baxter welcome Kelly home with the gentle bark that informs me of my children’s arrival, and not the one he employs to warn me of something menacing or unfamiliar. The door creaked open, and I could hear the faint whisper of the kids on the front porch. There was a sudden quiet, during which I assumed they kissed each other goodnight.

Kelly’s shoes plunked on the floor. She tiptoed into my room. “Mom?” she said, “Mom?” Her voice raised in alarm.

“In here, sweetie,” I said, swinging my legs around to the floor where Paul had planted his size 13 feet every morning. Kelly walked in and sat down beside me.

“I think a raccoon or something got to the nest,” she said, and tears gathered in the corner of her eyes.

“It’s okay, honey,” I said. “What’s wrong? Did tonight go okay?” I took her head in both hands and tilted it up to face me.

“It was great, Mom. Really.” She was crying. Briefly, her expression showed relief. “Now it’s gone. It was going to bring you good luck.” She looked around, wiping her cheeks and then waved her hands towards the darkness

“The robin’s nest?” I asked. Kelly nodded. “It already did, honey. Now go to sleep. You have an early morning.” I stood and walked her to the bathroom, and myself to my own bed.

When she left for work at 5:45, the sky was just pale enough for me to see her bicycle whir to the stoplight and veer towards town.

Kelly had gathered the eggshells and put them back into the nest. There were a few scattered bits on the porch, but whatever had eaten it had swallowed the inside whole. The trough held the pile of fragments. They were so blue. Aegean, celestial, oceanic blue. I could not bear to think of the devastated mother robin. I wedged the nest into the dark interior of the juniper tree.

In the kitchen, I started my coffee and made my foray to the laundry room. Every morning my feet carried me there, unwittingly, to my children’s clothes. I folded them and put them in piles, which, with an ache of tenderness, I patted and pressed with my palm. With Paul gone, there would much less housework to do, at least until Thanksgiving. In six days, I would be back at the college, with a new school year of my own.

I opened the dryer, gripped the lint catcher, and peeled off the soft gray sheet. It was satisfying, as it always was. Something fell on the floor, bounced once, and landed square and whole. It was the orange shell from my jeans pocket, from the deepest ocean, from a beach somewhere, from a small boy’s hand. I went to Paul’s room and returned it to the cracked clay cup.

Marcia DeSanctis is the author of 100 Places in France Every Woman Should Go, a New York Times travel bestseller. She is a contributing writer at Travel + Leisure and Air Mail, and also wrote/has written for Vogue, BBC Travel, The New York Times, Creative Nonfiction, Tin House, Coachella Review, The Common, and many other publications. She has won five Lowell Thomas Awards from the Society of American Travel Writers, including one for Travel Journalist of the Year.

***

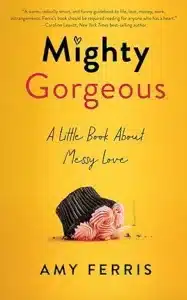

Wondering what to read next?

We are huge fans of messy stories. Uncomfortable stories. Stories of imperfection.

Life isn’t easy and in this gem of a book, Amy Ferris takes us on a tender and fierce journey with this collection of stories that gives us real answers to tough questions. This is a fantastic follow-up to Ferris’ Marrying George Clooney: Confessions of a Midlife Crisis and we are all in!

***