On a studio set a television camera scans onto a heavy-set Liberian – a professor at Northwestern University. Judy Woodruff asks him to “elaborate upon the internal ramifications of the situation in Liberia.” She means the slaughter. The professor, an exile himself says he has not been back to Liberia in twelve years. He doesn’t finish his response before I am back in Rateema.

We arrived late because our Landrover got mired in jungle mud. One minute we were on dry land, and in the next door deep in mud. Fearing mambas and scorpions I did little more than fret and watch John, our driver, hack off branches of palms with his machete and force them under the rear wheels. John drove us into Rateema in bare feet. His blue shirt and rolled-up trousers, his arms and face and hair were caked with red mud. He looked like a cake iced by a couple of children fooling around in their mother’s kitchen.

We were tired and hot. John drove into a clearing to park – there was no road – no one ever leaves or comes to Rateema other than on foot or by dug-out. Thatched huts were sited on top of tiny little hills. Each family occupied one little hummock completely cleared of brush – a distraction to pythons and mambas. The short bush grass around the huts shone with jungle dew. The sight was welcome, as jungle so oppresses me. It is impermeable. John had pointed that out as we bumped and reeled over the track of a path here and there. Through the jungle growth as mangled as wet hair, I could see paths black as night. John said the people never veer from them. They have been kept up for centuries.

The village chief and his advisors were already standing and waiting for us in the central clearing of the village. They could hear us coming from miles away. John went off to clean up and arrange to stay at another hut. Sally, the health worker and a Liberian, and I, sat on two string chairs while the villagers strolled over and squatted on the ground watching us as if we were a ball game, and especially me.

The time was six p.m. I turned on my short-wave radio. Dozens of eyes watched me pull the aerial out. When voices spluttered on the radio children, mostly boys, leaned back as if a baseball was batted to them. The others watched. I listened to the news summary and turned it off.

Sally talked about our work and translated. Women had gathered around, their eyes glistening over Sally’s green and while batik boubou. They smiled and pointed at it and back to each other giggling. There was no look of envy in their eyes. They were short people. The goats nibbling at the grass around the Chief’s house were also short-legged, like the cows.

As we talked about the project which was supposed to have brought a vaccination program to the village but had not, the sun sank behind the jungle somewhere. It was my job to find out why so we set the next day’s program and the Chief’s second wife brought us food: something heavy with fish in it. We ate and thanked the Chief.

He spoke a little English. He was middle-aged and kind and wanted to show me his house. In the rear, the kitchen was outdoors- protected from weather by a thick roof of thatch. Each of his two wives had her own partition, exactly alike. A huge pot sat in each hearth over a half-dozen rocks. From the eaves of the thatch hung gourds and clay pots suspended from plaited grass hangers. One wife was old, the other young. Both beamed at each other and me as I smiled and exchanged greetings in Twi. There is a certain language of kitchen pride among women. I caressed one’s pot (not daring to be any more partial than their mutual husband) smiling and nodding at them. I was pleased to be back in a kitchen. They smiled back their teeth perfect as a comb.

Sally says the Chief wants me to sleep at his hut. I accept for there is no other acceptable protocol; he knows I represent resources for his people and I know he’s a politician. I know too that I cannot myself distribute the sugar and candles brought for his wives and daughters and just give him the small carton. There was no point in bringing batteries or kerosene. This village in Eastern Liberia is so remote, even by African standards, that not even lanterns had found their way here.

Next to the latrine protected by a flimsy grass screen I took a quick shower by the light of my flashlight. In the dark the village children cannot peer so easily at this strange white female body in their midst.

In the Chief’s bedroom I lit a candle and lay down. Someone tapped at the door. It was the Chief again, urgently pointing at the window’s open shutters. It is stuffy in the room but the Chief looks worried and strides over to close the shutters with a hand-made hook.

“Country devils missus” he waves at the jungle beyond the window.

The clip on television airs only still photographs, no video, of a young man – a boy really – wearing only his underpants in a ditch raising his arms screaming for his life. Several rifles are aimed casually at him from adults in military camouflage. The voice over reports that the boy was slaughtered along with hundreds of others as Samuel Doe and Prince Johnson battle for the capital city. I know why he has taken off his clothes, but the commentator, the Liberian professor, doesn’t say it. Faced with slaughter the clothes state that he has parents with at least a little money to save him.

In the morning we were busy interviewing villagers and taking notes. I promise nothing to the Chief and his notables as we say goodbye but we realize he expects us to do something, anything for Reteema.

We drive onto another village, which is larger and is holding market day. We are expected for a meeting with village representatives. Sally and I crowd into an already packed tin-roofed meeting house. The village, we had been told, had been “difficult” to work with. Politics. A young man pushes his way through the open door and shoves a youngster from his seat and with no introduction or excuse starts ranting to us and the assembly. The crowd tries to hush him up, but he continues. Sally looks alarmed. A few minutes later as I sit mutely, briefcase on lap, the crowd is getting noisier and noisier the tempo rising alarmingly. Sally pleads with me to leave.

We jump in the Landrover, John already at the wheel, and drive off, fast. In the right rear view mirror I can see the crowd pouring onto the track and starting to hit each other.

“Sally, tell me about Country Devils” I ask her.

“I can’t” she says. “It’s primitive stuff of country people and I’m not primitive. I don’t believe these things.” Her lips slam shut. She looks annoyed and frightened. I turn around to gaze at the endless pot-holed track with the jungle on both sides. It’s the same view out of both sides of the vehicle, miles upon miles. But I too, am glad we left the village.

John drives on through the jungle. He wants us to reach the provincial capital by nightfall even though there is no electricity there either but at least certain comforts and the sea. The air is sticky so he turns on the air conditioner. All of a sudden he became chauffer-like. He asks if the AC is too high or too low. “It’s fine, John” I say.

Suddenly two women just ahead of us run out of the jungle their head clothes unraveled. They are frantically headed towards us so John slows down but the women keep running past us as if we didn’t exist. This in an area where vehicles are rare as snow. As we pass them their faces are distraught and horrified. I keep watching them as John drives on. One of the women’s pagne – her skirt – is falling off but she keeps on running. I have never seen two adult women in Africa run so fast and in such fear.

John eyes them in the rearview mirror. “Country devils” he mutters.

“Sally” I ask again, “I think I better know something about the ‘Country Devils’ if we are going to get anywhere with this project.” She looks at me, her face too is apprehensive. She seems to be elsewhere. John slides a glance at me, his hands on the wheel. It’s a glance that knows that I know something already that I shouldn’t know.

“What happened to those women back there damn it!” I look Sally straight in the eye. “Something happened. What is it?”

“Alright,” says Sally, “but you mustn’t tell anyone you heard it from me.” She touches John’s shoulder. John nods back to her.

“Country Devils are creatures in the forest. I don’t believe this primitive nonsense of course. I went to university…but since you insist…” I nodded. “They exist only to harass the women. That’s why we have so much trouble in that last village” she says. “The Country Devils came into town while we were there at the meeting.”

“They came into town while WE were there? How do you know?” I demanded.

“Don’t you remember that man who upset the meeting?”

“Yes.”

“He was telling them in Twi that the Country Devils didn’t want the meeting and they were waiting at the edge of the village, behind the market place, for us to go. They were trying to scare the village.”

The story is long.

Country Devils are devils They wear hideous masks. They scream and appear any time of day or night. They scream a scream no one should ever hear. The women are scared to death of them. If a Country Devil comes to a village, he makes a dreadful cry and all the women run to their houses and lock the doors and cower inside. The Country Devil dances around the houses peaking in through the reeds, and mocks them trying to make them look at him. He says to them – oooh go ahead and look at me – I can see youooo – hoo. But if they do they will never have children and if they are pregnant they will lose their child before it is born. The country women are terrified of them. The devils are very powerful. The women are completely controlled by them.

“Is that what happened to the two women out of the jungle back there?” I asked.

“Yes” she says.

John laughs. He says “of course, a Country Devil scared them so much they dropped their pots and ran home.” He chuckles to himself. He sounds so indifferent.

“I never want to hear a Country Devil scream” says Sally. Her eyes are terrified.

Later at a supper grilled over a fire at a small hostel, Sally, without a man around, tells me more.

By the time she was through I am informed and unnerved. My brain tells me Country Devils are nothing more than men in homemade masks, members of the Po secret society, known in Liberia for centuries designed to control women. But women too have their secret society, but it is not aimed at terrifying men, rather to protect themselves and children. The “devils” are men you see every day. They go off in the bush where they have hidden their masks and outfits and they come out and scare the women – and anyone in their way. They are the bogeymen of the politicians. Where the country is so poor that even sugar is to vied over and where cash hardly exists for regular transactions, the “devils” come in handy for scare tactics. Is this the Liberian version of storm-troopers I wondered.

In Liberia an Americanize name means you are on top (Doe, Watson, Tubman). If African, then on the bottom.

My presence and even Sally’s had already set up the system for competition. If the right party couldn’t get the goodies our project offered, then no one would. That was the work of the Country Devils in the village we had been hounded out of.

“What would happen if I, a white foreign woman, ran into a Country Devil?” I asked Sally.

She looked at me as if I was crazy.

“You would be killed like any other women” she said.

“Do you really believe that? You? Sally a modern woman?”

She looked at me over the candle and very quietly she said “I would not have gone on this trip alone. With you it was alright.”

“Well, I hope I run into one” I said. “He wouldn’t scare me for a single minute.”

Sally said nothing. We both went to sleep, sharing a room. But I wondered what a

Country Devil looked like and made sure the shutters were tight.

A week later I left Liberia after a long hard overland trip back to the capital. We had trouble with bandits. At a crude barrier in the jungle, John shoved his foot on the pedal and broke through it. They didn’t shoot at us. We didn’t stop until we reached Monrovia.

I could tell there was trouble coming and soon. In Monrovia a huge tent next to my hotel was holding nightly revival meetings. They were presided over by a blond former television evangelist from America. He preached in English but that didn’t stop him from raking in thousands of dollars from the local Liberians. The air in Monrovia felt as heavy as silt.

As my airplane landed in Ghana to take on passengers en route to Geneva I looked out of the window and saw open terrain and a few frangipani trees dotting the airport terminal. This was the world I knew. It had sky and sunlight and air. For the first time in weeks I felt relief.

I never went back to Liberia even though I made friends there: the kind of Liberians who had opportunities to leave but did not. After all it is their country they kept insisting. They would make it go right somehow, eventually. No, they didn’t think they were in that much danger. The current dictator would go and things would get better. The real Liberians would take over from the oligarchy of Americo-Liberians.

They are dead now. The kind of death in which a jeep at night splatters the gate and the windows and the children inside – all of them. The kind of screams to you never ever want to hear.

The professor and Judy Woodruff are still talking. “Why don’t you tell them like it is?” I hiss at the screen “you devil you.”

***

Looking for your next book to read? Consider this…

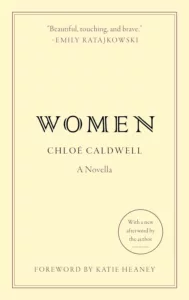

Women, the exhilarating novella by Chloe Caldwell, is being reissued just in time to become your steamy summer read. The Los Angeles Review of books calls Caldwell “One of the most endearing and exciting writers of a generation.” Cheryl Strayed says ‘Her prose has a reckless beauty that feels to me like magic.” With a new afterward by the author, this reissue is one not to be missed.

***

Our friends at Corporeal Writing continue to offer some of the best programming for writers, thinkers, humans. This summer they are offering Midsummer Nights Film Club: What Movies Teach Us About Narrative. Great films and a sliding scale to allow everyone the opportunity to participate. The conversation will be stellar! Tell them we sent you!