My second-grade classmate Roz’s small digits pranced on the piano fingerboard. I heard light raindrops and a singing wind. Effortlessly she lifted her left hand up and over her right hand to sound three high notes before bringing it back down to play a chord. Roz had been taking piano lessons since nursery school and I was jealous. The music launched a magic carpet ride. I imagined tinkling brooks, shimmering streams, chiming bells.

She made it look so easy.

If only I could play the piano like that. “Can I take piano?” I begged my mother. “Please.”

“You realize you have to practice. Every day you have to practice. Thirty minutes, forty minutes.”

Oh yes, I understood. Piano was something you need to work at, Miss Simon my new teacher explained. Each week she inspected my fingernails. “Keep them short.” I tried not to stare at the hairs growing out of the mole above her lip. Instead, I looked down at the pink spot on my left hand, the clue I’d used when younger to tell left from right.

“Keep your elbows raised,” she instructed. “Your hands must be in the correct position. Remember your fingering.”

I looked at the sheet music she handed me to practice. My first solo. I’d been looking forward to this moment. I’d imagined it many times, being handed music that referenced a waterfall, shimmering stars, or fairies dancing on rose petals. But the title of the piece was, The March of the Brigadier General. The illustration showed a man on a horse, and I felt betrayed. Somehow Miss Simon didn’t visualize me as a girl who loved pretty things that flew and fluttered daintily in the sky or danced about in slippers and a filmy lace dress. No, I was a heavy boring lug marching hut two three four down a fortified road flanked by identical soldiers. Is that what I was, a soldier? Not really a girl, but a boy in disguise.

I was never a tomboy. Always a girly girl. The girl who played dress-up wearing grandmother’s cast-off hats with beaded veils and white gloves. Alone or talking to our beagle, I would pretend I was an actress, a southern belle, someone’s long lost aunt. But I was a bossy girl. A girl who yelled when she didn’t get her way like in the poem, “There once was a girl who had a little curl right in the middle of her forehead. And when she was good she was very very good and when she was bad she was horrid.”

As a very small child I’d hide behind my mother’s skirt when strangers came to visit. The older I grew, however, the more I wanted to be heard. Noticed.

The language of music was supposed to be one of my strengths. (I’d been told I’d inherited my great-grandmother’s beautiful singing voice.) But when I looked at the symbols on the sheet music pages, my fingers resisted playing the tune. I’d heard The March of the Brigadier General, courtesy of Miss Simon several times. Jaunty, is how she described it. “Practice those staccato notes,” she’d said. A march into battle, complete with the carnage in Southeast Asia featured each night on the evening news, did not strike me as a cheery piece.

I was too much of a coward to tell Miss Simon or my parents that I simply did not want to play the abominable March of the Brigadier General. Three weeks in a row I left my sheet music at home. It sat inside the piano bench unpracticed. It wasn’t an ugly piece of music. It had a number of grace notes and a descant. Perhaps if it had been titled, Parade of the Gypsies or the Procession of the Unicorns, I might have visualized it differently. But the idea of a pompous military man astride a horse was repugnant.

Just before my piano lesson, which I took at school while classmates were at recess, we had snack. And I remember that day we had pink lemonade and cookies. The lemonade was full of pulp, very sour, and I threw it up. I vomited because I was so worried about telling Miss Simon I’d forgotten my music again that I doubted she’d believe me.

Instead of being guided by the interior self I’d imagined, the one who was eager to speak her mind, I fell back on old habits. Too afraid to say the wrong thing, I stayed silent. A demure little girl, who eventually told her mother, “Actually I want to stop studying piano with Miss Simon. I don’t like her. I don’t think she likes me.” This was said with my sincere belief that certainly if she assigned me such an ugly piece of sheet music when she gave such pretty music to my classmate, she held me in low regard.

Now I look back and think, probably she gave me that music because she wanted me to practice the staccato technique, learn to be more percussive with my hands. And why did I think those were masculine traits? I’d already begun to dribble a basketball and loved ping pong, but I decided I didn’t like the rat a tat beat of the drum in this particular piece of music which justified my refusel to practice.

My piano lessons were suspended, until my mother found another piano teacher, a college student with braces on her teeth whom I visited on Saturdays. This new teacher gave me choices when selecting my music and encouraged me to write my own compositions. By sixth grade I’d become infatuated with singing. Planning to use my knowledge of the keyboard for rehearsing voice parts in choir pieces, I looked forward to joining Glee Club the following year.

*

My parent’s voices were hushed and nervous. “There’s something important we need to talk about,” they said. “It has to do with Mr. Gleason the music teacher.” They were speaking about the Glee Club Director. My Glee Club. “There’s been something published in the newspaper. Names. An incident in the men’s room of a restaurant.”

I was confused. Were they explaining that men were sometimes physically attracted to each other? Women too? Were the roles of masculine and feminine not as clear-cut as I thought they were?

The arrest occurred, they told me, because the activity occurred in a public place and sex is private. I tried to imagine two men kissing. One would need to be the leader and one the follower. I visualized two men waltzing, one of the dancers guiding the other into a graceful turn and immediately thought of the discarded piano solo from three years earlier, “The March of the Brigadier General.” Maybe the Brigadier General was not just a boring soldier, solely focused on marching into battle, Maybe, he was thinking about gracefully dancing, baking bread, or building a house; a complex human.

I began to ask myself, why I’d ever thought low tones were stronger, or high tones light and sweet. Loud. Soft. Slow. Fast. Music could become anything I wanted to imagine.

My mind opened to all the possibilities. Perhaps I could play that piece of music.

I pulled out all the sheet music in the piano bench and started searching.

***

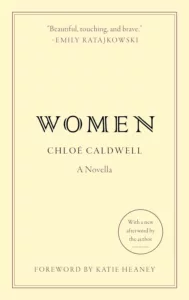

Looking for your next book to read? Consider this…

Women, the exhilarating novella by Chloe Caldwell, is being reissued just in time to become your steamy summer read. The Los Angeles Review of books calls Caldwell “One of the most endearing and exciting writers of a generation.” Cheryl Strayed says ‘Her prose has a reckless beauty that feels to me like magic.” With a new afterward by the author, this reissue is one not to be missed.