It began with the books. During the years when I was breaking up with my husband, I struck up a friendship with a librarian for a rare books and manuscripts collection. I don’t know how we began talking about it, but somehow, I got wind of the collection of books about witchcraft.

I had been thinking about witches. Don’t we mainly imagine them as persecuted women? Burned at the stake? Offered impossible choices like the ducking stool where you were drowned and innocent or alive and guilty? Women who understood plants and herbs. Women who refused to follow the rules. But I began to wonder if the worst part of the witch trials was that perhaps that these women were desperate. Perhaps the love that they once had for their husbands had ebbed away. Perhaps they did pray to the devil, work spells, curse whoever hurt them, because they felt that God was not listening and had abandoned them.

I’m not sentimental about the printed book. I’ll happily read on a screen as much as a page, but there was something about this particular archive. When you enter a rare book collection, the ritual is part of it. First, the shedding of belongings – no bag, no ink pens, nowhere where you could secrete a page. The seat at a leather desk with slips of paper to bookmark passages and weighted snakes to hold the books open.

I had never felt more witch-like in my whole life than those years when I was getting divorced. We lived in an American suburban house with blue shutters in a quiet neighborhood. It’s easier to write about anything else than it is to write about those days. When I say that I felt witch-like, what I mean is that I felt pursued by lawyers and mediators and courtrooms, as if a stern face was peering down asking: Does she deserve her children?

We go through life innocently enough until something happens to make us think otherwise. I had always thought that divorce courts were completely fair, or maybe I had absorbed so much propaganda from men’s rights groups that I actually thought that courts side more with mothers. That’s not really the case. After I divorced, I found more and more women come to me asking me for my advice – how to survive it, was it worth it? In most cases, children were involved. They would say to me: I love my children,but all that extra I do, all the work for children and home that I absorb for your husband – most of the time, no one thanks me for that, or even recognizes it.

But those days in the archive, I was not divorced yet but trying to lose myself in leather-bound tomes that smelled of earth and ink. All of the books were written by men. They were brought out on a trolley, some of them placed carefully in white cardboard boxes or folders. When I touched the leather of their covers and spines, I wondered how many women had handled them, or if the volumes were more used to being held by men. Are objects just things? Could love or hate pass from a human hand to paper?

One of the books on the trolley was printed in the 1500s: The discoverie of witchcraft by Reginald Scot. An English country gentleman, why would Scot write a treatise arguing that witchcraft could not exist? Was it because his life was defined by women? His mother who cared for him from infancy when his father died. Then there were his two wives, the latter who saved him from debtor’s shame, and his daughters. Was he actually protecting the women in his life? It is neither a witch nor devil but glorious God that maketh the thunder, writes Scot.

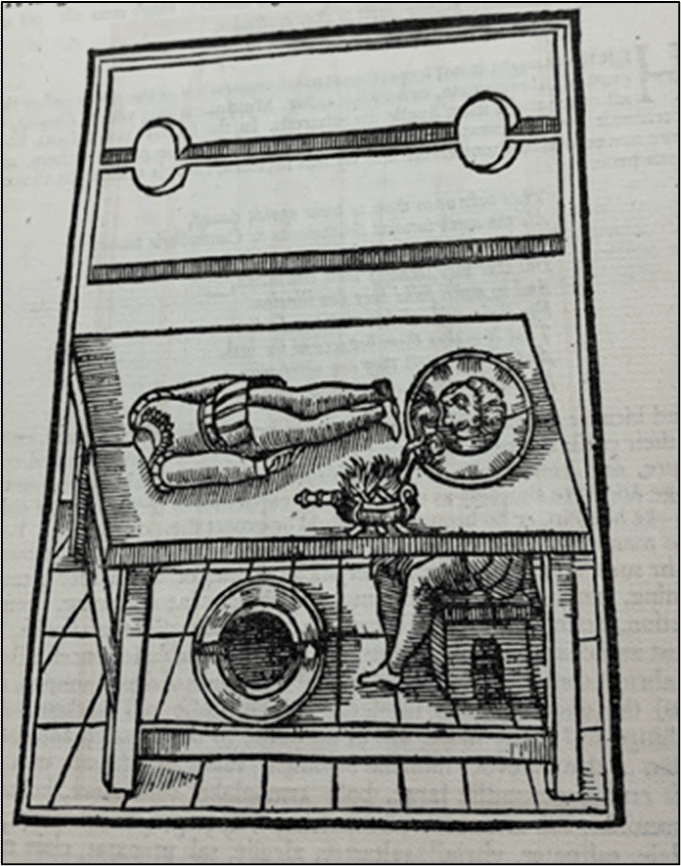

In The discoverie, Scot works through the superstitions about witches logically, impassionately, but he also seems to take great pleasure in exactly what he explores and describes the rituals and stories in great detail. Often Scot seems to mock the believers in his narrative, like one man who told the story of the witch’s bridle. The man complained of how a witch would come to him every year and slip the witch’s bridle over his head, at which he would transform into a horse. Scot tells how the storyteller complained to an old man of how the witch would ride him hard all night as far as the witch’s ball, where the witches would strip and dance naked around bonfire. Scot seems to recognize that the tall tale is actually an instruction for controlling and disciplining women. Bridle the woman before she bridles you. Violate the woman before she violates you. Each story Scot tells only to show its folly and yet the stories themselves are compelling. Like for example, a drawing of the ritual where one could supposedly remove their head. Scot labels it: To cut off one’s head, and to laie it on a platter which the jugglers call the decollation of John Baptist. What order is to be observed with great admiration, read page 198.

Scot still admires the finery, the fakery and deception. Under the table the rest of the man’s body is revealed to remind us of the illusion, but the illusion is compelling.

Later on, Scot lists the names of demons, detailing beliefs about each one. How vividly these characters leap from the page:

Raum or Roam is a great earl, seen as a crowe, but he putteth on human shape at the commandment of the exorcist. He knows things present, past and to come and reconcileth freends and foes. Gamigin is a great marquesse in the forme of a little horsse, when he taketh human shape, he speaketh with a hoarse voice, disputing of all the liberall sciences; he bringeth also to passe, that the soules, which are drowned at sea, or who dwell in purgatorie, shall take aierie bodies, and evidentlie appeare and answer to interrogatories at the conjurors command.

With his love of detail and his logical denials, perhaps what Scot is saying is that it’s fine to indulge in horrifying stories of debauchery and evil, as long as we don’t use it as an excuse to enact evil in real life. When the old women accused of witchcraft are utterlie insensible and unable to saie for themselves, and much less to bring such matters to passe, as they are accused of, writes Scot, who will not lament to see the extremitie used against them?We have our own witches – women who like the witches of old cannot live in the boxes they are put in. Women who are shamed and doubted in public, regardless of who is wrong or right. I could not live in the box I had been put in. Night after night sleeping alone while my ex-husband stayed up late and slept in the spare room, except if he wanted perfunctory sex.

The only thing that Scot finds magic in is love. For if the fascination or witchcraft be brought to passe or provoked by the desire, by the wishing and coveting of anie beautifull shape or favor, the venome is strained through the eies, though it be from a far, and the imagination of a beautifull form resteth in the the hart of the lover, and kindleth the fier wherewith it is afflicted.

Maybe romantic love could be a kind of magic, but when I was reading this book, I still did not have it, did not feel it in my life. Maybe though its opposite – an anti-love – could be true: a kind of venom or bad spell to make a person sick and exhausted. I knew very clearly that I wanted something else, and though I didn’t know it then, I was going to find it. Because though divorce is a series of witch trials, this time neither did I drown or burn, but I did survive, and a new magic was waiting for me.

***

The ManifestStation publishes content on various social media platforms many have sworn off. We do so for one reason: our understanding of the power of words. Our content is about what it means to be human, to be flawed, to be empathetic. In refusing to silence our writers on any platform, we also refuse to give in to those who would create an echo chamber of division, derision, and hate. Continue to follow us where you feel most comfortable, and we will continue to put the writing we believe in into the world.

***

Our friends at Corporeal Writing are reinventing the writing workshop one body at a time.

Check out their current online labs, and tell them we sent you!

***

Inaction is not an option,

be ready to stand up for those who need you