By Alli Blair Snyder

“What do you eat for breakfast on the morning of your son’s death?”

Sarcasm flirted with the tip of my tongue as I was carefully wheeled into a steel elevator. My nostrils flared in protest, but I knew it was better if I kept my mouth shut. Sobs kept erupting when I opened it. We spun and the metal doors slid inward, revealing a gaunt and grey-faced gargoyle. Except the gargoyle was a hospital patient, and she was glaring back at me. “Sallow.” I tasted the word in my mouth for its accuracy. That’s how I looked. My husband and his mother stood like statues behind me. Who would we become from here?

My skin hung from my bones in a lifeless sag. My arms in my lap bore the track marks of non-existent veins and the many painful attempts to dig around for them; blood seeped in red blossoms through the white bandages. My boney hands clutched a worn journal in my lap. I assessed my outfit in the elevator door reflection; I was wearing a baggy blue sweater my dad got from the Walmart up the road and a pair of Eric’s sweatpants. I don’t even remember if I put them on, or if someone else did. My body had been prodded, exposed, and moved around like a science project for the past week. I looked up at the sign on the wall of the elevator exclaiming, “Joy to the World!” My glare hardened to stone.

I ran my hand along the back of my neck and pushed away the errant nips of hair leftover from the haircut; I realized I hadn’t showered since before then. After we finally got out of the first hospital Monday night, Eric took me for ice cream and haircuts to calm down after the scary weekend we had. I didn’t even care how it looked. I just slapped a sparkly headband back on and we went home to cuddle, relieved. We didn’t realize we were in the eye of the storm.

Assessing my reflection during the elevator ride, what crossed my mind is how a woman puts on mascara on the morning of her husband’s funeral. I’ve always wondered how someone could have the strength to lift their arm to carefully swipe a wand over their eyelashes and pull on something as trivial as stockings before they bury the love of their life. I saw myself wearing that same sparkly headband from my haircut and a sheer pink Chapstick, despite my hollow appearance otherwise. Remember the alien from ET when they try to make him look like a human? I kind of looked like that. Half human playing dress-up.

But I guess I do understand now, how you can still get dressed on the day your life has imploded. We look for normalcy, even in the middle of tragedy. On the worst days of our lives, the gears keep turning. We hold on to the small things, the ordinary things, the things that feel like home. Mascara, stockings, headbands, Chapstick. Things that remind us that somewhere, normal and peaceful days existed. And that maybe they would exist again. Right before they wheeled me into the elevator, Eric and I decided against a funeral but agreed on cremation; then we handed the little bundle back to the nurse. They said he was perfect, over and over again. At the first hospital, when I was in so much pain, I couldn’t see straight, and at this one. And now we’ll never see him again. That’s the disaster I found myself in during that elevator ride. I grabbed at normalcy in my sparkly headband, pink Chapstick, and wondering what I should have for breakfast.

I imagine she wasn’t trying to be flippant with her question about what we should eat, my mother-in-law. She’s all business, all the time. Practical as salt, as she would tell you a hundred times over opening Christmas presents. Always toothpaste or a calendar. I guessed it was morning, so she was asking what we should have for breakfast. That made sense. I am normally grateful for her no-nonsense efficient energy, but I didn’t respond to her, sarcastic or otherwise. There was something lurking at the edge of my brain that I was trying desperately to shove away, so I just watched myself in my reflection thinking about how we got here.

I arrived at this hospital on a Tuesday by rickety ambulance, with a catheter taped to my leg and fear running a marathon in my heart. The ambulance worker kept telling me I was going to have to name him Todd if he delivered him mid-drive; my awkward laugh turned into hysterics and he had to stab me with another needle. We didn’t have a name for him yet. We talked about naming him at the first hospital, but they said he was perfect, they said I was fine, they sent us home for ice cream and haircuts. When the ambulance arrived, I was wheeled straight to a room and hooked up to every machine available to stop my uterus from doing her job entirely too early. My parents and my sister came to decorate my room with a little Christmas tree and twinkling colored lights. I said they didn’t have to, but they said it made things feel homier. Normal. Human. By what the doctors said to us last night, I calculated that this day on the elevator was a Sunday. Last night when I pushed him from me, Eric shouted excitedly, “December 20! That’s a great birthday!” The doctor mercilessly pushing on my stomach to pull out my placenta quickly responded, “Actually, 11:59pm. December 19.” Our wedding day was just over a month ago. It seemed like another decade.

Eric and his mother continued to respect my outward silence during our metal enclosed descent. We hit the first level with a jolt, and the gargoyle disappeared to reveal a whirlwind of brightness and busy. Nurses, visitors, hospital workers all whisked around a blue circular atrium; voices and footsteps were echoing at me from all sides. Every person seemed totally unaware that the world just ended. I guessed it was just my world, then. I looked back over my shoulder at Eric’s face as he pushed me forward. He looked like I felt. Dead inside. Not even human. I tilted my face upward to the beams of light cutting through the glass above. I noticed dust floating through the air catching the sun. It looked beautiful for a moment. But I flicked the thought away; nothing was beautiful to me anymore. It was just dirt.

I felt hands on my arms, and I dropped my face back down to ground level. “Hi babe, are you hungry?” It was my mom. My dad stood behind her with trays of food.

She crouched in front of me smiling; I ached for her smile to be real. But it wasn’t. She was looking for normalcy too. People try to feed you when your world ends. It makes sense, even broken half-humans need to eat. I pictured her making pancakes for me when I was little, to remind me and my siblings that everything would be okay. “Nothing can be bad when you’re having pancakes,” she would say. I knew she was being strong for us, and I knew she was being strong for me in this moment too. I thought that its probably just what moms do.

“I’m not a mom anymore.”

There it was. The thing I was keeping at bay, the thing my mind was dancing around with all of these other thoughts. Human brains are funny, that way. They do what is needed to keep us safe, but they can’t always protect us. The thought fluttered across the front of my brain when I wasn’t paying attention like an errant, unassuming butterfly before I could stop it. And it morphed into a bomb.

My chest exploded and my breathing became heaves. I looked down and my hands began to clutch at my stomach, pulling at my sweater. I was empty. He was gone. The bloodied bandages on my hands and forearms caught my eye and I grabbed them with opposite hands to rip them off. I relished in the sudden sting on my skin as hot, salty tears filled my vision. A wild animal was letting out a guttural scream, and as I looked around, I realized the noise was coming from me. I thrashed in my chair and tried to push myself up with the handles to run a thousand miles away from this hospital where my baby died, and my world ended. I whipped my head frantically looking for Eric so he could come with me. I wasn’t going anywhere without Finn’s dad.

My face became suddenly engulfed with pink pillowy cotton and I got a nose-full of coconut-lime. I was eye level with the freckles on my mom’s chest. She always smells like this; I bought the same lotion in Key West. It smelled like home. I felt her compress my arms to my sides firmly. I stopped struggling and sobbed into her as my tears soaked through her top. I heard concerned murmurs over my head and Eric’s hardened response to whoever rushed over during the scene I made; always protective of his wounded-animal half-human of a wife. My mom interrupted them and calmly asked, “Could you please point us in the direction of the chapel? My daughter just lost her child.”

As I sat in the chapel eating in silence, I had my answer. On the morning of your son’s death, you apparently eat blueberry yogurt. The colors from the stained-glass windows threw pictures all over the quiet room. I felt like I was moving in slow motion, and I could feel my mom watching me and waiting. She had one hand on my wheelchair and one hand holding my journal for me. Barely swallowing down the yogurt around the knot in my throat, I looked up at her. She smiled, again, the same pained one. I finally spoke without a wave of sobs. “Mom, I don’t know how I will ever be happy again. I can’t picture myself smiling or laughing. I can’t picture Eric happy again either. I don’t understand it. I don’t feel normal. I’m not me anymore. He died, and I think I died too.”

She took a deep breath, and told me, “Alli you will feel normal again someday. And by that, I mean you will feel human. You might be different after this. It will take a long time, moment by moment. You will feel joy and you will feel grief. Sometimes at the same time. You will smile. You will laugh. Eric will too. It’s okay to lose a piece of yourself in this, but it will show you who you are. Al, I promise, you will rise again. And when the next hard thing happens, you will rise from that too.”

I asked her immediately, “But how?” She said, “With us. And with hope.”

Eric said we should name him Finnick, our favorite character in the Hunger Games. I almost said, “No, not that name,” but it caught in my throat. I wanted that name so badly. I had dreamed about that name. I loved it. Eric loved it too, I could see it in the golden flecks of his green eyes when he explained that it comes from the name Phoenix. A rising from the ashes. He said that from this traumatic experience (my body going into labor four months early) Finn was going to rise from it, and everything would be okay.

Finn. I wanted to yell it after little toddler scuddles and scream it across a soccer field and write it on birthday cards and text it to him furiously when he was home late. “FINNICK MICHAEL SNYDER, where the hell are you??” I wanted to use it in all the small, ordinary, human ways. I wanted to say it out loud for a lifetime, his lifetime, and my heart was ripped open at the thought that I wouldn’t. But this little human was meant to be named Finn; for the short time that he was here, and forever after that. Instead of whispering it to him as I put him to sleep, I now have it tattooed on my arm where his head would have rested. Five days before Christmas, five feet from me, he lived for five minutes – and then he was gone.

The sun kept rising in the sky and the world kept spinning. It is clear to me now that a rising was to come. We thought it would be Finn’s. But, and I wouldn’t realize this for a long time (just like my mom said) – it would be mine. My rising. Our rising. My husband’s, and our family’s. Everything my mom said in that little chapel – it turned into a bit of a prophecy. Even down to her ending it with hope. A few months ago, I found out I was pregnant again. We waited nearly five years to try to get pregnant after losing Finn. Without knowing what my mom said that day, Eric suggested that we name this baby Hope. It was perfect, just like they told me Finn was. And then we lost her too.

A miscarriage. A week later, Eric lost his job in the middle of a global pandemic. Another disaster. Different and also the same. I thought it was going to break me, but then I remembered. Here’s the thing about what it takes to rise from ashes – the roadmap of how you did it gets etched into your bones. We remember, not just our own capability of rising, but the rising of all who have come before us. And those who came before them. As humans, we are hardwired to get back up again. It’s in our blood. Even if it takes a long time, we find a way. To be human on this earth is to experience loss. To fully live is to relentlessly rise from the ashes.

As I write this, the morning sun is beaming through my windows. Tomorrow is Finn’s fifth birthday. It’s been a few months since we buried baby Hope. Our two rescue dogs are snoring lazily on the couch, and Eric flies by me to grab coffee before heading back to his work-from-home office upstairs for his new job. He kisses my head and flashes me a smile. My bangs are pulled back with a headband, and my favorite pink lip balm is swiped on my lips. On our Christmas tree hangs two little red stockings; one with an F and one with an H. The colors of the twinkling lights are bright. I notice little dust particles floating through the air and catching the light, and I think to myself how beautiful it looks, even if it is just dirt.

My joy feels different now; it sits in my heart next to my grief, like my mom said it would. Normal and peaceful days do exist again. Everything is settled in a way that sometimes makes me anxious, as if I’m waiting for the next disaster to come. But I remember that when it does, because inevitably it will, we will rise again. We will grab onto each other, and the little ways we find normalcy and pieces of home. We will pull out the map etched into our bones of how we did it before. We will rise a little bit every day, with our friends and families around us, and with hope in our hearts. We will string together ordinary things to remember we are human.

On the day Finn died, I wondered inside of a metal elevator who we would become. It feels like my answer is – fully human. Painfully broken-open and healed again. And again. Forever in healing. Existing in both joy and grief at the same time. Holding on to each other and the people who love us. Rising from the ashes like a phoenix and finding hope in all that we do. On the window in my hospital room, Eric wrote For Finn in marker, to remind me to keep going. That I could get through anything, even someone digging around in my arm with a needle, for our baby. Now we both have this tattooed to remind us the same thing. For Christmas this year, we are adding a new one to remember that we can rise from anything for the hope of our future. For Finn, with Hope.

This time of year can be painfully bittersweet; maybe this year even more than most. The twinkling holiday lights throw shadows around the places our loved ones would be; they can remind us, too, of the things we do have. Life has a way of being relentlessly beautiful, even when it’s hard to see it sometimes. It has a way of always coming back around, too. We rise, and we fall, and we rise again. As I look around my calm and ordinary home, I notice the shadows of my babies not here. I know I’m still a mom, and its painful and beautiful to acknowledge it. But the light lands on all the things I have in front of me, and what is to come. Joy and grief, together. Hope for the future. I glance above me, and my eye catches a piece of paper tacked above my desk. It’s a ripped-out page from my old journal, the one that I kept vigorously when I was pregnant with Finn. I wrote it the week before he died. It says, “You see, nothing lasts baby. Not the good, nor the bad. The world keeps spinning no matter what. The sun always rises, even on the darkest of nights. Just grab onto hope.”

I smile to myself, and the moment I read it, Eric yells down from upstairs, “Hey babe! What should we have for breakfast?”

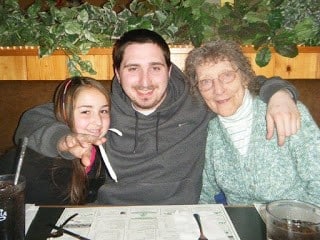

Alli Blair Snyder is a storyteller. When she isn’t writing about her grief or buried in a book, she is snuggled up with her rescue dogs and husband in their little Pennsylvania town. She is a writing professor and Ph.D. candidate in Leadership theory, focusing on shame and resilience. She is also a Medicine Woman and Mental Health Coach who fiercely advocates for becoming the expert of your own life. Find her on Instagram @allisonislivingbravely or on her website www.alliblairsnyder.com.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Megan Galbraith is a writer we keep our eye on, in part because she does amazing work with found objects, and in part because she is fearless in her writing. Her debut memoir-in-essays, The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book , is everything we hoped from this creative artist. Born in a charity hospital in Hell’s Kitchen four years before Governor Rockefeller legalized abortion in New York. Galbraith’s birth mother was sent away to The Guild of the Infant Saviour––a Catholic home for unwed mothers in Manhattan––to give birth in secret. On the eve of becoming a mother herself, Galbraith began a search for the truth about her past, which led to a realization of her two identities and three mothers.

This is a remarkable book. The writing is steller, the visual art is effective, and the story of what it means to be human as an adoptee is important.

Pick up a copy at Bookshop.org or Amazon and let us know what you think!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~