Resonant Imaging By Cynthia Stock

I recognized the radiology tech, a gray-haired woman named Danielle. A ponytail, looking as apathetic as Danielle could look after a long day, limped down her back. Lufkin, Amarillo, and North Dallas complicated her lilting drawl. She didn’t recognize me, but I remembered her.

Shortly before I retired, I transported a critically ill patient to Danielle’s subterranean world. The MRI room reminded me of the Chilean miners, trapped for days without light or contact with the “real” world, struggling to stay sane while facing off with death in a very small space. My patient, fully equipped with a ventilator and nine life sustaining IV infusions, required two ICU staff members and one respiratory therapist to travel to MRI. When we arrived, Danielle’s face collapsed into a web of wrinkles.

“I don’t think we have enough MRI safe pumps for all those drips,” she said.

I knew the patient’s blood pressure hardly tolerated a quick change to fresh IV tubing, much less a complete stop of one of the drips. “Let me call the doc.” I don’t remember which one. None of the doctors either experienced or understood the logistics of taking an ICU patient to another universe far, far away from critical care for a diagnostic that ultimately, would not, could not, alter the plan of care. After a terse risk-benefit analysis and an explanation of the equipment dilemma, the doctor canceled the order.

“I’m so sorry,” Danielle said, resigned. Her head nodded, side-to-side. I remembered using that gesture to voice my own frustration with job responsibilities. Her body expressed regret more clearly than any words.

“Not your problem. Thanks for trying.”

Danielle helped push the patient and his mechanical paraphernalia down the hall to the elevators, something some of the younger techs would never do. Danielle and I, almost the same age, found ourselves conjoined by a dated work ethic.

Facing my own MRI, I slipped into my “health-compromised” persona. Danielle explained things about the MRI as if I had no medical knowledge. That was okay by me. I laughed at the irony of MS, not a master’s degree, although I had one, but Multiple Sclerosis. The acronyms gave me two separate identities, neither complete. My first symptom of MS appeared in the early 70s.

Fresh from nursing school I remembered all the landmarks I memorized for my anatomy class. Mixing some sterile saline in a vial of the white powder of some antibiotic, I bumped the plunger of the syringe against my wrist. It felt numb. I finished giving the drug to the patient. Then I traced from my inner wrist up to my elbow and mapped the roadway of my radial nerve. No feeling, cause unknown. Just as mysteriously, the feeling came back.

I didn’t interrupt Danielle’s explanation of the procedure, didn’t ask if she remembered me or our day of futile labor. The almost saccharine sweetness of her voice grated, but then it soothed. Or maybe it was the Xanax I’d managed to sneak before a tech led me though the labyrinth of the radiology maze. I was almost ready for the forty-five-minute claustrophobia challenge.

I often I wrestled with feelings of invisibility, except when it came to my career. I didn’t often tell people I was a nurse. At the gym, I didn’t want to hear about poor nursing care in such and such hospital or offer information in conflict with doctors who practiced medicine by recipe rather than individualized care. I only allowed my family the luxury of free nursing-medical advice. For my MRI, I didn’t want to be the retired nurse in MRI Room 2. You remember her, she took her job way too seriously. Such a control freak. I wanted to be the frightened, anxious person who loved to workout, read, write, hold her husband’s hand, and dote on her two new kittens.

Danielle secured my head in a padded support as if it were a precious piece of art in need of safety and stability. Six ceiling rectangles boasted a beach scene complete with striped beach chairs and cherry red umbrellas. I weighed the benefits of wine versus margaritas at the beach, while Danielle admired my ample veins, poked my hand, and inserted an IV. So far, so good.

“I’m gonna flush it with a little saline,” she said.

A jolt of cold shot from my hand towards my elbow.

“Do you know what we’re looking for today?”

I knew what I was hoping for, no new white spots highlighting a most unpredictable, aggravating disease. “They want to see if my lesions are stable.” Since I’ve had to stop taking my Tecfidera. I remembered losing seventy pounds in six months and then losing sensation as if I’d had what in the old days was called a pudendal block. Dammit, since retirement I can’t afford the drug that enabled me to work at the bedside for forty years. I didn’t say what I felt, nor did I mention the meningioma nestled like a pearl in the oyster of my frontal lobe. Anger can kill you just as easily as any disease.

Sixty-seven-year old backs become ardent protesters with immobility on a flat surface. Danielle eased a triangular pillow under my knees. My back stopped complaining. When she snapped the plastic cage over my head to keep it perfectly still, I ordered myself not to open my eyes again until the test was over. I’d done that once. Through the plastic matrix I saw an infinity of ivory plastic looming inches away from the length of my entire body. It closed in on me and spawned an adrenalin rush so potent I started screaming. “Let me out. I can’t do this.” Not this time. I had to get this done.

Danielle’s voice changed into a something hollow and distant. The table shuddered and moved by inches. “We’re gonna get started.”

I clutched the call bell, my panic button. It was soft, round, no bigger than a plum, but knowing my body slid through the gullet of a heartless, automaton, it became my lifeline.

I wanted to shout at the sounds. First a riveter. Then a jackhammer. A soprano wasp nesting in my ear. The thunderous NUNUNUNUNUN. I wondered about damage to my hearing. The sounds shattered any sense of time. The bane of my MS existence, bladder urgency, remained at bay.

Unlike other techs who occasionally chatted over the intercom, Danielle remained quiet. So quiet, I imagined the worst, a national crisis requiring all employees to go to designated posts as part of a disaster plan. A bomb threat that cleared the building and left the helpless and entombed. My favorite, a zombie apocalypse where the only safe place to hide was an MRI machine. A new story line for The Walking Dead. After a brief hum, the riveting started again.

I made it through the MRI. Danielle helped me sit up. My head spun for half a second. Danielle held my arm for support when I jumped off the table and headed for the dressing room. Danielle never recognized me. However, when she grabbed me, for the first time I noticed she wore a compression sleeve on one arm. The well-worn seam suggested Danielle had worn it for a long time. With retirement, I saw things differently. With retirement, I saw different things.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

File Under: Magnetic Resonance Imaging MRI; Volumetric Imaging Rate; Resonant Healthcare Imaging

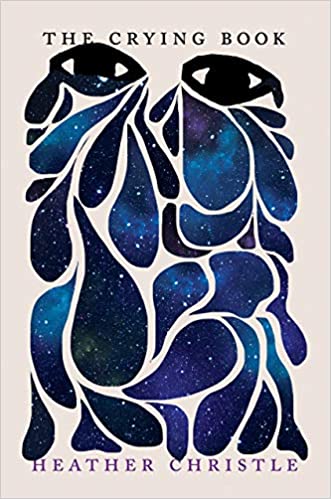

A book about tears? Sign us up! Some have called this the Bluets of crying and we tend to agree. This book is unexpected and as much a cultural survey of tears as a lyrical meditation on why we cry.

Pick up a copy at Bookshop.org or Amazon.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~