by Roz Weisberg

At Rachel’s first funeral for her father’s Uncle Milton, her mother leaned over and whispered, “Promise me when I die you won’t put your father on top of me. I’ll come back to haunt you.” Rachel nodded yes. She was ten. Ten years later, Rachel arranged the open casket, lavish spray of roses and lilies, and the details to make her mother look like a version of her alive self for the open casket. A hundred and fifty people moved from the chapel to the graveside where her mother’s coffin was lowered into the ground. Standing at attention, Rachel waited for her mother to scream from below reminding her of the consequences of breaking her promise.

Ten years and three months later, a closed casket, a modest spray of roses, a condensed twenty-minute graveside service where Rachel’s friends who never met her parents attended the burial of her father. Two groundskeepers wore blue jumpsuits and stood at the head and foot of the casket guiding it into another box as if it were a part of a Russian nesting doll set. The park insisted on the extra concrete box to protect the earth and preserve the casket, but Rachel thought it made it easier to mow the lawn. A third groundskeeper plunged the shovel into the mound of dirt. The rabbi recited the Kaddish, but Rachel could only hear the ringing of her mother’s shrill voice, “I told you not to put your father on top of me, I get claustrophobic.”

The rabbi’s words morphed together as he stepped up to Rachel in his black fedora and tore the pinned black ribbon over her heart. He stepped aside. When Rachel didn’t react, he cleared his throat and spoke her name. She didn’t quite hear him, her ears had been plugged for days, but followed his gesture. Stepping toward the graveside, the crisp air and bright bleached sunlight reminded her that it would soon be daylight savings though she wasn’t sure when the clocks were supposed to be turned back. She peered into the grave at the white concrete slab before taking the shovel and scooping up a blade’s worth of dirt. Steadying the wooden handle, she guided it over the hole, and with a last inhale gave her mother one last beat to air her discontent. Nothing. She flipped the shovel over; the rocks of dirt exploded and scattered against the cement. She plunged the shovel back into the dirt and returned to the white plastic folding chair.

The rabbi squinted, transfixed by something moving through the thin gathering. A hunched over old man in gray slacks shuffled up to the grave. His blazer too big, the arms to long. His small bald head sat on his shoulders as if he had no neck. Without turning around, he grabbed the shovel and scooped up some dirt, but the weight made him unsteady. One of the groundskeepers stepped out from behind the mound as the man coughed up and swallowed phlegm in the back of his throat and hoisted the shovel. It slipped from his grip, toppling into the grave. Before the old man fell forward, the groundskeeper pulled him back. The old man fell backwards on the groundskeeper.

Everyone gasped, their bodies jolted, the flimsy chairs legs gave out, and the first row collapsed like a row of dominos. The rabbi watched, frozen at the lectern. Rachel landed on her side. The other groundskeeper spoke into a walkie-talkie while another moved to help people stand up, dust themselves off and reset their chairs. The rabbi found his voice. “Is everyone alright?”

Rachel looked at the old man as she stood up. “Excuse me? Who are you?”

“Excuse you. Who the hell are you?” The groundskeeper had helped the old man stand.

It sounded as if the old man were speaking underwater. Rachel closed her eyes and took an audible breath, “This is Bernie Sussman’s funeral. My mother was Shirley.” Her own voice sound muted.

At the base of the hill a golf cart pulled up between the mourner’s cars. The driver in his blue suit got out and trekked up the hill.

“This is Stanley Leven’s funeral. Stanley was my wife’s second cousin. She couldn’t come, this hill woulda killed her.”

The man from the golf cart stepped up and introduced himself as the director.

“I’m here for Stanley’s funeral. Where the hell is Stanley?” The old man noticed the groundskeeper for the first time.

“I’m not sure sir. Why don’t I give you a ride and we can let these people continue their service?” The groundskeeper passed the old man’s arm to the director.

“Now, wait a minute. Let me think.” He tilted his head downward “Sussman you say?” He shook his head back and forth as if reading through an imaginary rolodex. “No, I don’t think I knew any Sussmans.” He tried pulling his arm away. “Must be the wrong funeral.” The old man took a last look in the hole, “That doesn’t look good.” He grabbed the director’s arm as if it were the bar on a walker and they waddled down the hill.

Rachel stepped to where the old man had stood and looked down. A groundskeeper grabbed a rake and maneuvered its teeth to pull up the shovel. Somehow, the metal edge of the shovel had chipped and cracked the concrete slab. A groundskeeper mumbled into his radio. Another golf cart arrived, another director climbed the hill.

The rabbi suggested he finish the service and offered final condolences, thanking the attendees. The mourners lingered as the director and groundskeepers conferred in a huddle. Rachel joined, glancing into to pit. The director explained, he’d never seen concrete crack like that, but he’d called for a replacement. Rachel was free to wait, but they weren’t sure how long it might take.

Rachel crossed her arms, the ringing in her ears echoed, “You promised me!”

The director tried to usher Rachel along, but she stood her ground. “I’ll go on my way as if nothing ever happened if you could reverse them. Put him in first and her on top.” She couldn’t gage the volume of her own voice though there some heads turned her way.

Her request was met with blank stares. The director mumbled into his radio and conferred with the groundskeepers before agreeing to the accommodation. Rachel turned to leave. Taking in the view of the paved LA River bed, her ears popped, the shrill ringing in her ear stopped as the groundskeepers lowered the crane and raised her mother’s concrete box.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

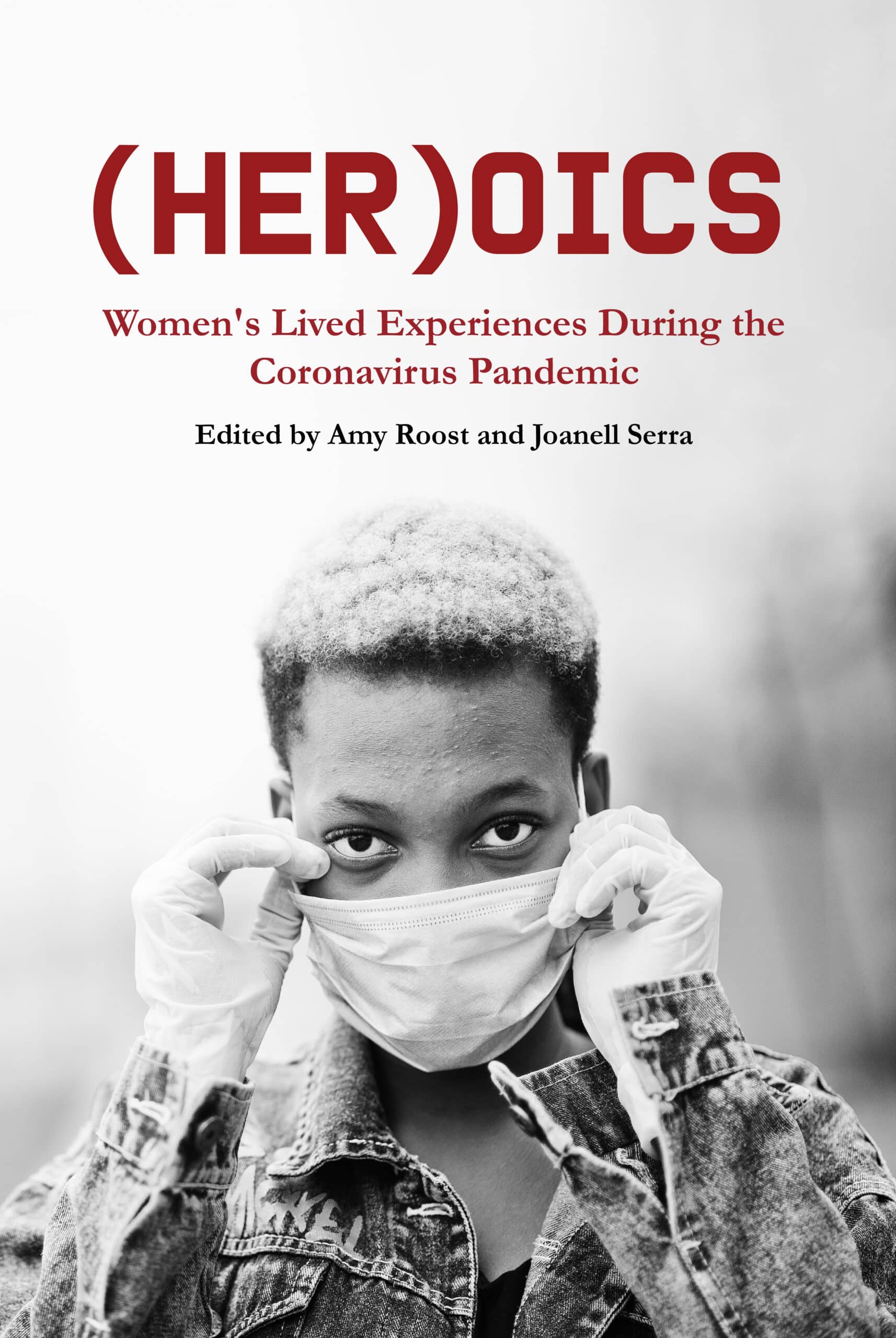

This past year has been remarkable, in the best and worst of ways. (Her)oics Anthology is a collection of essays by women about the lived pandemic experience. Documenting the experiences of women both on the front lines and in their private lives, this book is an important record of the power, strength and ingenuity of women.

Pick up a copy at Bookshop.org or Amazon.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~