by Beatrice Weber

I am a mother of ten Hasidic children, and I couldn’t protect many of them from the virus. The community they live in has flouted restrictions—and while I know my children are at risk, my hands are tied.

In mid-March 2020, my 7-year-old son, my youngest child, and one of three who lives with me told me he knows why this virus happened. “Oh?” I asked. I was in bed, sleep teasing me, hoping he’d get tired, too, and go to his room. “My teacher told me it is because we don’t say enough blessings. He said that if we say 100 blessings a day it will go away.”

My son is innocent. Like kids his age, he is impressionable. He was one and half years old when I left my abusive marriage, six years ago with four of my ten children. He attends a yeshiva and visits his father, a rabbi in Monsey, New York, every second weekend for Shabbos. I am fiercely protective of him, but when he is not with me, I cannot control what he is taught or what happens to him.

Sleep now a distant memory, I caressed his face and assured him that the virus is not his fault and cannot be undone with blessings. “We need to be careful, and we will be okay.”

But the next day, I was not so sure we would be okay. On my way to work, I see a message that had been making its rounds on WhatsApp groups. In pink letters, adorned with lilac flowers and green leaves, the virtual flyer, titled “Unique Protection,” stated that rabbis encourage women to upgrade their head covering from wigs to kerchiefs (more pious), and in this merit, we will be saved.

I closed my phone and continued walking. I spotted a Yiddish notice on a lamppost stating that the contagion is a punishment for schmoozing during prayers. We must be quiet, and this disease will go away. Quiet, I thought—the one thing I fail miserably at.

For many years, I had prayed daily, fervently. “God, please help me to become a ‘Kosher woman who does the will of her husband,’” I would plead, quoting the words of the Talmud. Please help me to do this. I want to be a good wife to my husband. I prayed and trusted that things would get better in my marriage. But it did not.

I was expected to be a meek, obedient wife. When I would try to voice an opinion, my husband would shut me down and get the children to mock me, until, finally, I broke.

It was seven years ago on Passover eve, before the first Seder when I left. My parents, older children, and the rabbis vehemently opposed me leaving. When my parents found out, they worked with the rabbis to try and take away my younger children. The six I left behind were lost and confused. They were angry at me for abandoning them. They couldn’t fathom the idea that I would leave. I was their mother who had always been there for them. And I left with a heavy heart, the most excruciating decisions I ever made.

I eventually received a Jewish Get from the rabbis and custody and a divorce in family court, but the feelings of betrayal never left me. Betrayal by my own family and my own God.

I felt lost and bereft, and I searched for another way to live.

Before Passover last year, a month into quarantine, my son pled with me to let him go to his father for the Seders. “I want to be there with my nephews,” he said. I assured my son that his nephews won’t be at his father’s Seder, since it is not safe to travel now. But I was not convinced of my own words. I had heard the rumors and seen the flouting of coronavirus restrictions. I knew that his father would risk infection—for himself and his children—to host a proper Seder with our grandchildren from New Jersey, against all guidelines. And I was not wrong – he did indeed invite our children and grandchildren and

Quarantined in my house, I lead a Seder with three of my children, joyfully singing the traditional songs and searching for the hidden matzoh, the afikomen. The sirens outside wailed, reminding me of the predicament we were in. The deaths in my former community mounted, peaking over Passover.

My friend who runs a nonprofit supporting young orphans in the community told me of the huge increase in requests for services. Families lost grandparents and parents, and communities lost rabbis, leaders, and congregants.

This became very real to me. The virus had infiltrated the community. And while I was hopeful that my children’s father and their community would take it seriously because the sheer numbers of infected and the dead pointed to a danger that required action, I was also skeptical because I knew what I would have done a decade ago. Instead of following the guidelines, I would have encouraged my sons to gather and study and covered for the men’s prayer gatherings. My belief that God would save us was so strong, I may have been compelled to trade my wig for a kerchief.

My skepticism was well-founded. By September, the second wave had reached the Haredi Jewish community in Brooklyn. My son’s yeshiva opened its doors while ostensibly following the rules that had been put in place to prevent the spread of the virus. One day I found myself in front of the dark grey building. My son’s teacher had called to ask me to pick him up. He had come down with a strep throat the week before, and he was still not feeling well.

I hesitated before entering the building. Though I am a mother of six boys, I have rarely ventured into the all-boys’ yeshiva building. It was considered immodest and unacceptable for a woman to walk the hallways—and besides, I never had a reason to.

There is another reason I hesitated: I no longer follow the strict dress code of my former community. On that day, I wore my curly bob and black slacks instead of the black mid-thigh skirt and beige tights expected of me. I had never gone near the yeshiva without my hair covered and a skirt over my knees, but I had no time to go home and change. My son wasn’t feeling well, and I was going to pick him up. He needed me.

I peered into the classroom over the teacher’s head and saw the children gathered, with no sign of any social distancing or facial covering.

I suspected that the guidelines were not being followed but seeing this blatant violation of the rules horrified me. What was I supposed to do now with my son? He was required to attend yeshiva, whether it felt safe to me or not. If I chose to keep him home, my ex-husband would use it as leverage and surely come after me for custody. I was torn between doing what was expected of me by my ex-husband and the community my son still belonged to or following my maternal instincts.

I chose the latter, filing complaints with the city and state health departments. I pulled my son from yeshiva, knowing I risked a potential battle with my ex who might take me to family court, a serendipitous reason why he should be granted custody of my son.

Weeks later, a judge in family court ordered my son to return to school, disregarding the flagrant violations. I comply, worried for my son’s health but also fearful of losing custody.

But for now, for then, I am still in charge. I do what I can protect my younger children, but what about my older ones. Who will protect them?

I don’t hear much from them. Since I left the marriage six years ago, there has been limited communication and it has tragically stripped me of any real relationship with them. They are angry that I left. I ruined their lives, they say. They went from being the children of highly respected parents to the children of divorce, shamed in the community. No one will want to marry them. They are damaged goods.

I don’t blame them; my heart bleeds but I could no longer sacrifice myself and my sanity.

Should I have stayed?

I have seven grandchildren whom I haven’t seen in years. I yearn to see and hold them. My children, too. I ache to be part of their lives and know how they are faring in these challenging times. But I am scared to call.

Will my daughter hang up on me like she did when I last called?

Will my son yell at me? I am too fearful, too vulnerable— so I sit at home and worry.

I worry that my children and grandchildren may not be okay. I am angry at a system that encourages them to ignore public health guidelines and rules meant to protect them. But I also envy them. I envy their faith and the unshakable belief that God will protect them.

But who will protect the rest of us?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

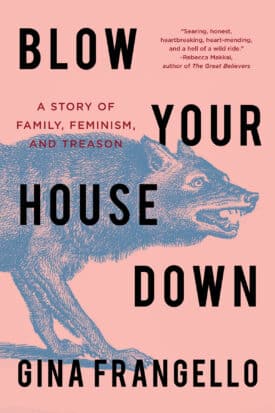

Blow Your House Down is a powerful testimony about the ways our culture seeks to cage women in traditional narratives of self-sacrifice and erasure. Frangello uses her personal story to examine the place of women in contemporary society: the violence they experience, the rage they suppress, the ways their bodies often reveal what they cannot say aloud, and finally, what it means to transgress “being good” in order to reclaim your own life.

Pick up a copy at Bookshop.org or Amazon.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~