By Katherine Flannery Dering

I spent days getting up early and clicking on various websites, eager to get my COVID shot appointment. And then, one morning, a friend sent me an email saying he and his wife had reserved a spot at a nearby CVS. I clicked on his link and got a spot two days later. I’ve now had one shot, and the second one is coming up soon.

I wasn’t always so eager to get a shot.

One afternoon back in 1960, my brother Johnny and I shimmied up the two trees in our backyard to escape a shot. They were a pair of plane trees about twenty or thirty feet tall, with pale, splotchy bark and a full summer complement of big, fluttery leaves. We’d climbed them many times before, so we made short work of getting fifteen or so feet up. I found a secure crook and waited, my arms around the trunk. Maybe they’d give up and the doctor would leave. It was a warm, clear day; I could barely make out my brother, hidden in the leaves of his tree. But through a break in the branches, I could see off to the Davids’ house a half mile up the road. I held my breath, hoping to disappear into the canopy.

It was eerily quiet. Our house was on a new road that had been created from a farmer’s field several years before. Behind us was a big cornfield. Across the main road that came up from the village were about twenty acres planted in wheat—my other secret hideout. I liked to sneak into the field and tromp down some wheat out in the middle and lie down there and look up into the sky. People raised dairy cattle and goats just beyond the David’s house, and there was usually some mooing and bleating from the herds. But a hoof and mouth disease epidemic had just rampaged through the area, and all the remaining livestock were put down, to make sure it didn’t spread. The quiet was ominous.

“Katherine, Johnny,” my mother’s voice suddenly called. And then I saw a man’s brown leather shoes below me. The shoes’ owner moved, and a bald head and dark coat appeared through the leaves and moved along above the shoes. “Zay ran zees way,” a man’s voice said in a thick French accent. “Zay must be here in some plaze.”

Three of the little kids—our younger siblings—were raking the area with their bare little feet. Did they think we were hidden in the grass? Like mice, they were always everywhere, opening my dresser drawers, drawing pictures with my Tinkerbell lipsticks and spilling the nail polish. It was Patrick who looked up. “They’re up there. They’re in the trees.”

A woman’s black flats and a seersucker, plaid dress appeared. Dark hair in a French twist. My mother’s voice had that “Don’t tempt me!” sound. “Come down this instant. You’re embarrassing me.”

We’d been living in Switzerland for a year now and the English-speaking doctor my mother had found had already given the little kids their shots. She’d probably negotiated a group discount. “Doctors are busy people. He can’t hang around all day. And I’m not paying for a second visit for you two.”

We gave up. Climbing down, I lost my grip for a moment and slid, gaining a big sliver in the palm of one had. I shook the hand and winced. Patrick smirked; he’d gotten one on us older ones. I felt like a condemned man in front of a firing squad. I knew that the inoculation would pinch, and that my arm would throb for days. A typhoid booster was a thing to be reckoned with. But what was worse was that I knew what was coming, and I couldn’t stop it.

***

In 1960, Europe and the World Health Organization were still battling the lingering health problems that followed in the poverty and rubble after WWII. Students at my school, the International School of Geneva, had to be tested each year for Tuberculosis—serum injected into the delicate skin on the inside of your forearm, covered with a bandage, and then checked by a WHO nurse who came back to inspect the site a few days later. If the skin bubbled up to a certain size, you were sent for a chest x-ray. I passed.

Before we moved to Geneva from Detroit, which was our real home, most of us kids had all been vaccinated or revaccinated for smallpox, typhoid and tetanus. My little sister Monica, who was now almost three, hadn’t had the small pox vaccination yet, because she had problems with eczema, and her pediatrician didn’t think it wise. But now there had been a small pox scare somewhere and she had to be vaccinated in order for us to return to the U. S. that summer for home leave. The twins, who had been born in Switzerland and were now six months old, also had to be vaccinated before the trip home. The rest of us needed various boosters.

The small pox procedure looked pretty barbaric to me. The doctor sliced a little cut on the babies’ thighs and slathered on some sort of goop, then bandaged it. They screamed, of course. That’s when Johnny and I ran out of the house and up the trees.

***

And now, sixty years later, another terrible disease to try to prevent. The Typhoid vaccination back then involved three shots and a booster every so often after that. It was a Typhoid booster that Johnny and I needed that day. The COVID-19 vaccination in 2021 is only two shots, although it sounds like we may also need annual boosters for a while. Unlike in 1960, though, I’m not running away from this vaccination. Quite the opposite. Before I secured an appointment, I had spent days getting up early and clicking on various websites, eager to get my COVID shot, eager to be released from the jail of sheltering in place.

The first shot was easy-peezy. The drug store was set up for an assembly line. I arrived fifteen minutes before my assigned time and checked in at a desk just inside the door. I was then sent to a line that snaked down a long aisle toward the back of the store, where the pharmacy had been set up for a crowd. The other over-65ers and I waited our turn standing six feet apart, on big red circles arranged to keep us socially distanced along an aisle that displayed Depends and other “adult incontinence” supplies. The shot itself took a few seconds—a quick jab and I was sent to a chair nearby, where the CVS employee/ ringmaster set a timer to go off in fifteen minutes, by which time I would show signs of an allergic reaction, if I was going to get one. Timers were going off every minute or two. “You’re done. Next,” the ringmaster would say. I had no after-effects to speak of, then or the next day.

***

Now I am in suspense again, like when I was 12, sitting up in that tree, knowing I would eventually have to come down. I’d have to let the doctor give me that shot. And now I have to do something similar. I’ve heard that more than half the people who receive the Moderna or Pfizer vaccines have a very unpleasant reaction to the second dose—body aches, fever, chills, sometimes even vomiting and diarrhea. My baby sister Julia, who wasn’t even born yet in 1960, said she had no problem with hers. And my brother Johnny, who’s a doctor now and got his second shot weeks ago, also had no problem. But there’s still a big part of me that wants to hide up a tree somewhere. I’m tempted to not take it. But then what? Hide from the world forever?

I came down from the tree that day. And in another week, I will go get my second shot. And this time, I know I am very lucky to have the opportunity.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

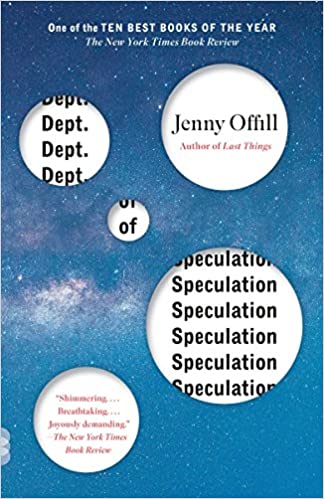

Although each of Jenny Offill’s books is great, this is the one we come back to, both to reread and to gift. Funny and thoughtful and true, this little gem moves through the feelings of a betrayed woman in a series of observations. The writing is beautiful, and the structure is intelligent and moving, and well worth a read.

Order the book from Amazon or Bookshop.org

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~