by Meredith Resnick

I am six. I am standing on the cement pool deck behind our brick apartment building in Yonkers. A sticky day in August. My body is wet. The pool is blue. The sky is gray. It is a weekday. All the mothers are lined up on woven beach chairs in a row that spans the chain link fence. All the mothers except my mother. There is a break between her and the other mothers. No chairs, no towels, just gray cement.

I stand in front of her in a pink bathing suit. My ribs stick out like a xylophone. I cradle my fingers between my ribs. She tells me to stop. You look insecure, she says, and lights a cigarette. I don’t know what insecure means but I stop. I shiver. She has called me out of the pool to put on a t-shirt to wear in the water because you can get a sunburn on overcast days. This is before we know that t-shirts in the water can make a sunburn worse. This is before we know a lot of things. Before I know a lot of things.

My mother hides behind large sunglasses. She wears a black and white bathing suit. She smokes. She pulls a towel over her squishy thighs. She hates her cellulite. She hates her body. She flicks ashes into a Fresca can and slides the lipstick-marked butt after it. I hear it sizzle. She lights another. I slip the t-shirt over my wet hair, over my pink shoulders. Good, she says. I can’t tell if she is looking at me.

My feet slap the cement. I’m back at the pool. I squat on the steps in the shallow end then let my body glide through the water until my feet no longer stretch for the bottom. The water holds me. It wants to hold me. It teaches me to swim. This part is easy. I float. I touch the bottom. I buoy to the surface. I hold my breath.

One year ago I knew without knowing that I must teach myself to swim. I don’t know what that meant until years later and I am an adult. I don’t know what a lot of things mean until years later. There is a large gap in my knowledge of things that a daughter should understand.

I learn to swim by gulping air and holding my breath. I look like other children splashing in the water, trying to learn.

My mother does not look like other mothers sitting on the deck.

For a reason I don’t understand, I am afraid she will abandon me. This happens when I’m in the water, always when I’m skimming the bottom of the pool, furthest from the surface, from her. I force myself to count. To not panic. One to ten. Ten to twenty. The longer I wait the more my panic grows. I am frantic. I burst from shallow depths in my t-shirt and search for her. Scan the long line of mothers. But she is not like other mothers. She sits alone in the corner, with her cigarettes, after the gap and I forget, I always forget.

When I wave she waves back, a limp hand in my direction. She blows smoke into the summer air.

As if on cue the other mothers rise from their chaises and lower into the pool like some synchronized dance they all know. In the water, all around me, mothers with black hair and brown hair and blond hair or hair tucked beneath flower bathing caps pull their children in slow circles around their thighs, even the kids bigger than me. Through my chlorine-stung eyes, mother and child are one.

Except.

This time I look for the red hair and the orange tip of the lit cigarette. I push up the edge of the pool and run to her, then run back to the edge and scoop the water up with my hands and dumped it over my head. I don’t know why or what I am doing. My mother blows more smoke. She laughs. She laughs so hard I think she might cry. She laughs so hard she tells me to stop. I don’t stop. I wave to her. Silly excited waving. Simmer-down excited.

“Enough already,” she says, cigarette between her teeth. I stop. I stand there. I want to hug her. I don’t hug her. She doesn’t like me to touch her. I turn and jump into the water and swim in this vast sea, warm water touching every part of me except what is beneath the t-shirt. That part feels cold. That I want to wrap my arms around her too tight, and sit too close, and touch her arm or leg is normal. This must mean there is something wrong with me or with my body where the t-shirt touches. She is the mother; there is nothing wrong with her. But I don’t know that yet. There is so much I don’t yet know.

I peel off my t-shirt. I will get another sunburn. I let the water hold all of me.

***

I am thirty-three. I am meticulous about birth control. About preparing my diaphragm. When I use the foams, creams, and jellies, and the doughy sponges that never stay put. I lay in bed and watch my husband don the prophylactics, the Trojans that stick like glue, wrapped in the knowledge that as two mature responsible adults who are learning to grow together, we will know when it is time, when it is right, to grow our family.

My interior universe already knows no sign, time, or alarm clock exists. I don’t long for a baby who melts into me, who captures my hair between her fingers. I long to be the type of woman who does. I don’t fantasize about a real baby I can love, or dream of pregnancy the way some women do. I never stuck a pillow beneath my dress as a child and pretended I was pregnant. But I do now, as an adult.

I act “as if.”

I act.

I try.

I am trying.

I wonder if there is something wrong with me.

I am seven. My mother and I are in the den on the couch. Raindrops ping the air conditioner perched on the windowsill. It is morning. It is Christmas vacation. It is going to be a boring day. On her side, face creased into the pillow, my mother lights a cigarette. Her doughy legs fold into an L; the fetal position. Freckles, our miniature poodle, crawls into their right angle.

“Can we get a Christmas tree?”

“We are Jewish,” my mother says. Smoke streams into the air.

“Can we get a crèche?” It is a serious word. I understand serious words. I say I will take care of the baby Jesus all year, and that he can be a child for my Barbie doll. They will live in the crèche. My mother says Barbie doesn’t have a husband, is too young to have a baby, and that even if Joseph were the father, it wouldn’t be nice to leave Mary out and besides, the Baby Jesus doesn’t look like a Barbie would be his mother.

The girl who lives next door has a cross over the side of her bed at pillow height. In the middle of the night when she’s scared, Jesus makes her feel safe. It’s her secret with Jesus. This cross is made of wood and Jesus is nailed to it. The nails stick out of his palms, their flat tops painted red. His face is so sad. I wonder what Jesus was like as a boy. Did he like milk? Did he get scared? When I get scared I crawl into my parents’ bed. Fear and safety are how I feel close to them.

“I touch his feet every night. Want to touch them?”

“No,” I say.

“Because you’re Jewish?”

“Because he looks so sad.” Because he looks like my mother.

“He’s not sad,” she says, hands on hips.

I don’t answer. She leads me into the living room. Beneath the Christmas tree is a crèche. My friend hands me the baby. “That’s the same Jesus,” she says. “In case you didn’t know.”

“I know.” I cradle him in my palm.

I ask my mother to tell me the story of how I was born. We are on the high riser, in the den.

She lights a cigarette.

“I missed my period.”

I slide my foot across the cushion. I want to touch my mother in such a way so she doesn’t notice. It will be my secret. So slowly, like my foot is the medium from the Ouija board I got for my birthday. I move against my will but every bit my will, toward my mother’s leg.

“We brought you home and I put you in an infant seat, propped a bottle against a balled-up receiving blanket, and watched you drink it from across the room.”

I hate when she tells me about her period. And when she says she never held me. That she hated feeding me. Was afraid she’d drop me.

I look down into my lap then I look at her, smile. “But are you glad you had me?”

I don’t know that this is not a question all children ask.

My parents are older than other parents. I am only in second grade but I’ve already vowed to never be that old when I become a mother. In real life, my parents are not so much old, they just seem old—she is 42 when I am born in 1961, and my father is about to turn 44. I know my father always with gray hair, a bad back, and perpetual cancer that warrants lengthy hospital stays, and my mother with wrinkled skin, few teeth save for her silver bridges, and leg cramps that leave her toes curled like fists. My sister is 21 years older than me, and my brother 18 years older, and look more like the parents of kids my age. “That lady,” friends say, pointing to my mother, “looks like a grandmother.”

My mother exhales smoke. “I would never have an abortion.”

I have looked up this word. This word is in the grown-up dictionary, not in my children’s illustrated dictionary. I have checked.

“But you were our change of life baby. A great big surprise.”

She moves. The dog scurries. I can’t get my foot to touch her leg fast enough before she sits up.

Secretly I worry that my lack of desire to have a baby, to be pregnant, to carry a child indicate something fundamentally wrong with me. I’m afraid I’ve inherited my mother’s lack of baby desire and maternal instinct. That in some odd twist my own mothering instinct was tweaked in her womb. It seeps from my pores, a disease that takes generations to cure. But mine is not the generation for such miracles. Babies, with hands like rose petals and toes like creamy pebbles, are natural. My lack of maternal instinct—or maybe it is my mother herself?— is not.

***

The year my husband I adopt our daughters—two sisters, Russian, who are ten and thirteen when they come to us—I find the mirror I’d given my mother on her birthday long ago. She is eighty now. I’m thirty-eight. I’m packing her things. She can no longer live alone. Dementia has changed her. Softened her. She gazes at me sometimes.

But now my mother sleeps and I hold the frame. The metal warms in my fingers. The green patina features a slender silhouette, a metal woman peering back at herself in the mirror. I’d chosen this mirror for reasons I did not understand until now. To hold my mother’s gaze was like trying to balancing a gyroscope on the tip of your finger at the bottom of the ocean. This embellishment, this expressionless woman, was the face I’d memorized. It was all I ever saw because it was all she showed me.

For some there is the urge to develop. To move beyond. But for me, developing means deepening. My body remembers. It has become a kind of appendix that has collected the bits and pieces of my girlhood. Its captured the outlying events that inform but don’t define the story arc of me. What has deepened me has also wounded me, and the person who wouldn’t touch me may well have also loved me in their very particular way. These footnotes and asterisks about someone else also comprise the main narrative of mine, and sometimes it can be difficult to explain and understand. How could your mother have been like that? You’re nothing like that. I didn’t inherited my mother’s lack of desire or her inability to love. I am still trying to understand why that feels like a transgression.

So what happened; what really happened? It all happened. I won’t say that I raised myself. But, rather, that something larger than myself, than my mother, than any of us whispered in my ear to keep going. I never feel alone and yet, in many ways, I always feel alone.

And that is okay.

I am okay.

When you become a mother you become acquainted with the rights others take in telling you what motherhood is or, rather, what it should be. This goes for daughterhood, too. These are binaries, though, eithers and ors that appoint shame and pity to the ones who cannot give, and the others who don’t have something to receive. This fault line demands not a choice of one or the other but, rather, falling backwards into the depths and darkness. That is where you become. From this you emerge. This is what I’ve learned. To find myself there, no longer unseen.

Meredith Gordon Resnick’s* work appears in the Washington Post, JAMA, Psychology Today, Lilith, Los Angeles Times, Newsweek, Motherwell, Literary Mama, and the Santa Monica Review. Meredith is creator of the Shame Recovery Project, work devoted to healing the unwarranted shame of sexual (and other) traumas, and founder of The Writer’s [Inner] Journey, an award-winning site about the intersection of writing, creativity and depth. She is co-author of All the Love: Healing Your Heart and Finding Meaning After Pregnancy Loss.

*Her work also appears under Meredith Gordon and Meredith Resnick.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

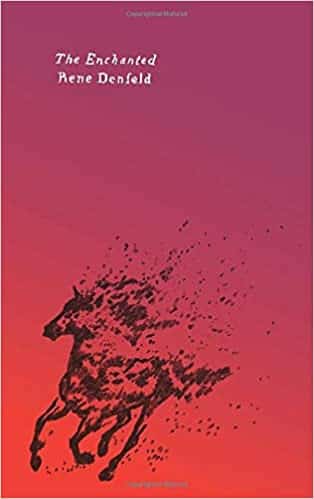

Margaret Attwood swooned over The Child Finder and The Butterfly Girl, but Enchanted is the novel that we keep going back to. The world of Enchanted is magical, mysterious, and perilous. The place itself is an old stone prison and the story is raw and beautiful. We are big fans of Rene Denfeld. Her advocacy and her creativity are inspiring. Check out our Rene Denfeld Archive.

Order the book from Amazon or Bookshop.org

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anti-racist resources, because silence is not an option

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Wow, Meredith, thank you for such a generous, visceral piece. I am in your debt.