Long ago a friend handed me a book called Five Sisters: memoirs by five 19th-century Russian anarchists whose fierce idealism, at the cost of tremendous personal sacrifice and a certain cold-blooded willingness to commit murder, helped bring about the assassination of Tsar Alexander I in 1881. It was full of photos of these young women, dark-eyed and intense, with masses of dark hair. “They remind me of you,” my friend said. I was young, but no revolutionary—I couldn’t even watch violent movies. Still their single-minded, fearless gaze, conveying pure refusal, struck a chord. Even more: all that hair.

In 1958, my mother had made me cut my hair. I was twelve, about to enter seventh grade and, said my mother, to be grown up. I had gotten my period and begun wearing a bra, and she was following the rules of her time, place, and class, which decreed that becoming a woman meant cutting your little-girl long hair short.

I resisted—I liked my shoulder-length hair, straight but with a slight wave, and very thick—but she was determined that I be properly inducted into womanhood. She dragged me to what was then called the beauty parlor, where a peroxided stylist gave me what was known as a bubble cut, and I joined the ladies of the hair roller brigade under the dryer.

I was so miserable, hating my new bubble head, that behind my back my mother asked my friends to tell me it looked great. (They did in front of her but ratted her out later.) The worst of it was that I couldn’t grow my hair back and have what I had before, since after that cut it stopped being straight and became bushy and unmanageable. I had been inducted not only into womanhood but into a long struggle with pincurls, rollers, and hair spray, and later straighteners and French braids, none of which could tame it. I didn’t know that this change in texture was due to normal hormonal changes of puberty and would have manifested eventually anyway, so it felt doubly unfair.

In college, I learned from Glamour magazine that now, in the liberated sixties, a “girl” no longer had to cut her beautiful long hair when she joined the workforce, as long as she kept it perfectly polished and groomed. My hair was long again but it was too late. Hairdressers didn’t know what to do with it. Over the years I went from long to short to long again, always trying to make it behave against its nature. I fought my hair for decades.

In cutting it off, my mother was obeying the precepts of a faith practiced by women of a striving immigrant middle class. She revered Eugenia Sheppard, an enormously influential fashion columnist for the New York Herald Tribune, and her temple was Loehmann’s, a famous discount store where the labels were ripped out but discerning shoppers recognized quality brands by the linings. Her scripture was the laws dictating how a woman should be and dress and look in the 1950s and early sixties.

My parents, children of Russian Jewish immigrants, had made it out of Brooklyn into a spanking-new Long Island suburb, and like many others at the time, my mother wanted more than anything to be American. “Immigrants emulated what they considered to be upper class,” social historian Carole Turbin told me. My mother’s rules “related to class and assimilation, wanting to be a lady and be respectable.” A lady dressed formally (a dress, nylons, and in the summer, white gloves) when she went into the city; never left the house without makeup on; wore a girdle so her backside didn’t jiggle; and kept her hair cut and controlled. During a family road trip around 1960, we were stuck in Lincoln, Nebraska, for a few hours, wandering around downtown while my father took the car to be fixed. My mother fretted the whole time because she and I were wearing shorts, which according to her creed were inappropriate for a city street. How you dressed was who you were—not that you chose your clothes to express who you were, but that by following the rules you defined yourself as existing within specific boundaries. Parading through a city in shorts put us outside those limits.

She pressured me relentlessly to match her notion of how I should be. We fought over clothes she wanted me to wear: a lemon-yellow spring coat; a silk party dress whose bodice she had altered to be so tight that sitting down was uncomfortable. When I tried to refuse that coat she got really angry, and I think now that she was frightened by what might become of me if I didn’t fit the template. Like the Russian anarchists, I was rejecting rigid social constraints. But unlike them I had no philosophy pointing me toward an alternative vision.

My mother had sewn me beautiful dresses when I was little, and probably to imitate her, as little girls do, I started sewing on her basement machine, beginning with simple gathered skirts and progressing to complicated outfits. Like her too, I knitted. In college I knitted an entire dress while reading Jacobean drama from a textbook large enough to lie open on my lap. After college I got married, as so many girls did, largely because I didn’t know what else to do with myself. Living in Chicago the next winter, I went to Marshall Field every Saturday to join the yarn department knitting circle whose instructor helped me knit a tweed suit with cardigan jacket and pleated miniskirt. I still wear that jacket but every time I put it on I think of those afternoons when I could have been doing something else, and feel a vague discomfort.

But only recently did I seriously ask myself why I did all that sewing and knitting. For I had no vocation for making clothing. I didn’t even particularly enjoy it. What I did have a vocation for—though nobody noticed, including me—was writing. My very first published work, around age 13, was a letter to American Girl magazine responding to a story they had printed. I had studied the published letters and deliberately imitated their gushy tone and quirky comment at the end. It worked, although now I ask myself why I didn’t just write in my own voice. Probably it never occurred to me that any voice I might have was worth listening to. But I date the origin of my writing career before that, to the moment I “flew up” (as the transition was called) from the Brownies to the Girl Scouts and decided that the writing badge was the only one I wanted. While I was too impatient (and still am) to be really skillful working with my hands, I have no trouble rewriting a sentence fifty times to make it perfect. So why did I spend all those hours at a sewing machine instead of a typewriter?

I want to say, because she cut my hair. Because in my mind hair, clothes, and the Russian anarchists are mixed up together. They’re all about identity.

*****

“If you are a Black woman, hair is serious business. Your hair is considered by many the definitive statement about who you are, who you think you are, and who you want to be,” writes novelist Marita Golden. And in different ways, hair was and is about identity for women of all skin colors. Empress Elisabeth of Austria (1837–98) was renowned for her extraordinary beauty and above all for the thick chestnut hair that fell below her knees. “If I were to have my hair cut short in order to get rid of an unnecessary weight,” she confided to Constantin Christomanos, who tutored her in Greek during the two or three hours required each day for her hairdresser to construct her heavy crown of braids, “the people would fall upon me like wolves”—as though her hair were what made her their empress.

A teenager I know created an Instagram self-portrait that began with a photo of her magnificent Afro puff. “I love my hair,” she explained. “That’s who I am.” Philosopher and novelist Rebecca Newberger Goldstein writes, “As a child I already knew that I possessed long hair that was trapped inside a short cut. I also figured out, as I got older, that I was a freethinker trapped within Orthodox Judaism, a feminist trapped in paternalism, a novelist trapped in the rules of my own rigorous academic discipline. My hair’s struggles have been my struggles.” Some women liberate themselves by cutting long hair short. Google “cutting my hair freed me” and you find many testimonials to this effect. But I say, with poet Honor Moore, “My power resides in the length and thickness of my hair, and I will never give it up.”

Many cultures see hair as a conduit of energy with magical and spiritual potency: thus Samson’s oath to God not to cut his hair gave him extrahuman power until Delilah tricked him and had it cut off. Marita Golden notes that for Black women, hair “is an expression of our souls.” Kelissa McDonald, a Rastafarian, told Allure, “For me, locs are almost an extension of my crown chakra energy. They act as antennas, you know? My hair helps me to discern the intentions of people, actually.” Melissa Oakes, a member of the Mohawk tribe, explained that her hair was waist-length because indigenous people “are the roots of this land, so these are our receptors that are connecting us with the land. It’s an old saying: The longer your hair, the closer connection you have to the earth.” No wonder twelve-year-old me didn’t want a haircut.

Empress Elisabeth also complained to Christomanos, “I am afraid that my mind escapes through the hair and onto the fingers of my hairdresser. Hence my headache afterwards.” I know exactly what she meant. I’ve always had the notion that my hair is so thick and unruly because I think so much. But unlike Elisabeth, I got headaches because my thinking energy stayed stuck inside my head. In any case, cutting the hair interrupts that life force, as happened to Samson—and, I would say, to me in that beauty parlor, just as the sexual and psychic energy of womanhood was waking up.

In her pioneering feminist book The Female Eunuch, whose central claim is that women have been effectively castrated, Germaine Greer defines castration as “the suppression and deflection of Energy.” In exactly this way cutting my hair severed my connection with my own identity and deflected the energy that could have been focused on writing into those hours at the sewing machine. My mother tried in myriad ways to force me into the mold of the perfect fifties female, but this one is the wound that left a scar. Unable even to imagine what I might choose to do, I fell back on what the culture and my mother were telling me I ought to be doing. While writing this essay I read and heard numerous stories of traumatic haircuts inflicted by mothers on daughters, motivated largely by wanting the daughter to fit into the cultural constraints required of females—the girdle we all wore.

***

My mother’s girdle mostly lived in a drawer because it was so uncomfortable she rarely wore it. But she never stopped trying to justify flouting the girdle rule, and her rationalizations never quite satisfied her. Probably this was why she never made me wear one. But for years I wore a mental girdle. The Russian anarchists went beyond refusing the limits that bound women in their time; they tried to destroy the stifling social order that oppressed everyone, in order to create a new society. I think I also perceived in them, dimly, a determination to achieve an authentic identity. And today I understand as well that refusal isn’t enough: one must go beyond that. For me it took years. When I saw their photos and felt that kinship, I was still at the beginning of an evolution. I had managed to flout my mother’s expectations, getting divorced, living alone, and working freelance. The moment I left my husband, I started to write. It didn’t end the headaches, but it got some of that stuck energy out of my head. I discovered that writing is when I feel most essentially myself. But it took my hair a while to catch up.

***

Unruly, wild hair disturbs people, especially on a woman’s head; thus Medusa was a monster who had to be slain by a hero. So the only thing most hairdressers I handed my hair over to could find to do with it was cut it off, so short that it couldn’t curl much—until I found Rose, a hairdresser unafraid of curls. I was still in thrall to the idea that my hair could only be managed if kept fairly short, but it now curled as it pleased all over my head.

In spring 2019, I let it get longer than usual because I was too busy to go for a cut. But it looked ok. Time passed and it still looked fine, so I let it slide a few weeks more. Then I asked Rose about keeping it long. “What you want is a curly shag,” she said, and gave me one. It looked fantastic. Just as important, it felt fantastic. I went home and let it grow some more.

Several inches later it dawned on me that I had my original hair back—my heavy, unruly mop—and that I loved it. I loved the feel of it—not just its weight, but the visceral sense that weight gave me that I was completely me again. Representative Ayana Pressley perfectly describes that experience in her video revealing that she has alopecia. About five years before, she says, “I got these Senegalese twists, and I feel like I met myself fully for the first time. I looked in the mirror and I said, ‘Oh, there I am!'” For me it was mystical: I felt solider, stronger, braver, that I had attained a deeper level of being me. And it still looked really good. I saw that my tough curly hair only worked when it could be itself, and I had freed it to do that. It was a revelation to discover how happy I was to have it back, even though it took quarts of shampoo to get clean and half a day to dry. Rose’s cut was so excellent that my hair usually looked good no matter what I did with it. And if it didn’t, I didn’t care.

That, at least, was my theoretical position. Then the coronavirus put it to the test. The lockdown hit just before I was due for a cut. The hair salons closed. So for a while I had more hair than I ever bargained for. I retrieved hairstyles from my past: pony tail! French braids! Twists! What’s now called a “messy bun”—the only kind I could ever make, lucky for me it’s now an actual style. I unearthed my hoard of old barrettes and went to buy more, only to discover that they’ve mostly given way to clips. Ok, I got clips. And I found antique barrettes on eBay.

Then my partner and I needed masks, but masks were still hard to find. I never sew anymore, except for occasional utilitarian repairs, but I still have fabric scraps left over from garments I made long ago—not to mention my mother’s sewing cabinet, a neat little piece of furniture dating back at least to the 1940s that still contains some of her sewing leftovers. So I rifled through everything and came up with enough fabric and old bits of ribbon and ancient packets of seam binding to make two masks. True to form, I was impatient, so they looked rather slapdash, but they did the job. I took a certain satisfaction in retrieving those old skills, plus the whole process resurrected a weird feeling of connection to my mother—the past returning into the present, but on my terms.

When the salons reopened, I returned to Rose with still more hair and told her how much I loved it. So we kept it long, and I went home and watched it grow more, until its weight pulled barrettes out of place and and gave me a headache. Eventually we settled on shoulder length, manageable though not particularly neat. I no longer mind it sticking out wildly, though. The imperative to look “good” has slipped still further away, and I’m left with just the satisfaction of having my hair back—and owning myself.

***

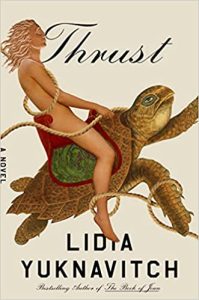

Have you ordered Thrust?

“Blistering and visionary . . . This is the author’s best yet.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

***

Great essay. I was 11 in 1958, so grew up in the same ambiance. I, too cut my hair short and sewed and crocheted. My short hair fit the image of a businesswoman, too. I, too, sewed masks in 2020-2021 – about 200 of them! I’m retired now and had thought I’d go back to my late 60’s elbow-length hair. Unfortunately, at my current age, my hair is too thin and weak to grow long.

This is a fascinating read. I have my own hair journey, which is similar, but different. As a 3rd grader, I asked for a short haircut bc I wanted to look like those ladies in the Salon books. With all the curlers! My plan backfired when I ended up with a short haircut and I looked like a boy. I never cut my hair so short after that.