I am wandering around inside The Quadracci Pavilion building of the Milwaukee Art Museum, the building that’s shaped like a giant cruise ship run aground. Or maybe it’s supposed to be shaped like a bird with its wings outstretched or, possibly, a beached whale, its bones bleached by the sun. I am far from home in a lakeside city loved by tourists but I am not on vacation. Instead, I have driven from southern Minnesota to Milwaukee, a drive that normally takes 5 hours but yesterday took me eleven in sleet and snow, so that I can visit my daughter. So I can bring her home.

Yesterday, as I drove the ice-covered roads, I saw car after car after semi after truck in the ditch, and was witness to an accident. I called my daughter along the way with updates, letting her know I was still coming. Letting her know I’d be there soon. But travel was slow. Too slow, it turned out. The last time I called, telling my daughter that I’d be just a little longer, she sobbed that they wouldn’t let me in late. They didn’t have adequate staffing. I missed visiting hours by 15 minutes. They would not let me see her, they would not let me in.

Had she looked out the window of her hospital-like room, she would have seen me looking up for her as I drove my Jeep to my hotel just one block away. So close yet so far. I parked my Jeep in a nearby ramp, wiped away my tears, pasted on a smile so I could present myself at the front desk. Checked in to my hotel. Found my way to the elevator. Made my way up to my room. After eleven hours on the road, bumping and sliding along, with my daughter just out of my reach every mile of the way, my body was sick from motion and emotion. Quaking in my legs. Queasy in my gut. Grieving in my heart. I set down my suitcase and the bag of things I’d packed to bring for my daughter – the soft purple quilt I made for her high school graduation, a book, her favorite lipsticks, some art supplies, a warm sweater – and then, too exhausted to get to a chair or the bed, I laid my body down on the floor.

The next morning, the treatment center staff made an exception to the “no guests at mealtime” rule because I had traveled so far, and they allowed me to join my daughter for breakfast. Arms full with my coffee and to-go breakfast and my daughter’s quilt and things, I was buzzed in and rode the elevator to reception. I signed in, was met by a staff member and told they would not let me bring in my daughter’s quilt because it’s not store bought – regulations of some sort – so I leave it in the locker with my coat, my purse, my phone. Another elevator ride. And there she was. My daughter not looking like herself. Hair buzzed short. Eyes with dark circles. Her olive skin sallow. More like a lost little girl than a woman of nearly 20 years who two months previous was traveling the world, who one week ago was attending college and living on her own.

I pulled her into my arms and kissed the top of her head. She smiled some, but cried, too. She was hesitant. Quiet when she talked. Unsure of her responses. She is not doing well. Sick. Mentally ill. Eating disorder. All sorts of words are used to describe what is going on with her but I don’t see diagnoses, I see my daughter and I can see that she is not herself. Unless this shell of herself is a new normal for her. I don’t know. I will love her no matter what state she is in – physical or mental – but now she is in a mental state that is not a good one and a physical state that is hours away and all I want to do is bring her home.

We had breakfast together. Me food from Starbucks. She a dietician-planned meal on a compartmentalized tray. She was eating fine until I brought something up that made her sad, caused her to stop. Somehow I said something else, trying my best to make it all better, and she started eating again. She finished almost all of her meal. I did, too. Then I was allowed to sit in on a meeting with her dietician and therapist. They are kind and I can tell that my daughter likes them. I wanted to talk about a plan to get her treatment closer to home so my husband and I can see her, support her, help her. But as we talked, it was made clear that this is where my daughter needs to be, that I would not be taking her home.

Meeting done, it was time for my daughter to go to programming. And time for me to leave but I did not know where to go. I took the elevator down to the mail floor. Walked out the glass doors then down the block, into the hotel. I took the elevator up to my room, dropped off Rose’s quilt, rode the elevator back down, stepped out into the cold, cold, air and started walking because I did not know what else to do. I did not know where to go.

I tried to open the door of a historic church so I could sit inside, rest and get warm – visiting churches during our travels is something my daughter and I like to do – but the door was locked. So I started walking again. I did not know what else to do. Soon I could see the lake not far away. How far had I gone? A mile? More? I saw the art museum, its great ship or bird or whale body beached there. I decided to go there.

I walk into the labyrinthian galleries of art hoping for respite but immediately I want leave. To get out of there and go see my daughter and take her home. But visiting hours aren’t until 4:30. Hours from now. And I can’t take her home. I am wandering in the neverland of parenting a young adult who makes choices of her own. Why can’t I still be the mom who can make the decisions for my daughter who is struggling?

But I’m not. So I am here, here in the belly of the whale or the bowels of the ship or stuck in the gullet of a giant bird. There is beauty all around me but I cannot enjoy it. There are sculptures by Degas, Russell, Rodin. There are paintings by O’Keeffe, Renoir, Monet. Photographs. Pottery. Furniture. Art from long, long ago and art from recent years. My daughter would love this place. If things were different and she was here, she would wander the galleries with me, comment on the pieces of art that she adores.

I wander amongst the sculptures and paintings, wending my way through another of the art-filled rooms when I hear a low thrumming. The noise fills my ears, ebbs and flows like water lapping on a shore. Puzzled, I look around, wondering about the source. Is it the heating system thrumming in the background? That doesn’t seem right. Museums are always so quiet.

I think about what a great semester my daughter was having; she had just switched her major from Chemistry to Studio Art. She has always been an artist at heart. Just yesterday she was a little girl smiling, laughing, pointing at artwork alongside her little brother as we walked through the galleries of the museum near our home.

I continue to wander around the museum, that low and constant sound buzzing in my ears all the while I am thinking thinking of how my daughter has withdrawn from college so she can get better. Thinking of her bravery in knowing she needed help and finding it. Thinking of the struggles she’s had these past three years. Thinking of how I do not get to drive her home.

I stop in a room, the art swirling around me. The humming continues and it is only now that I have stopped that I feel the vibrations in my throat, radiating down to my heart. I am the source of the noise. I, who so often sing and hum to bring myself joy and comfort, have been moaning deep and low, a keening hum.

I begin to walk again, still humming deep and low, and notice paintings of children with their innocent smiles and portraits of mothers and daughters together. These strong young women with bright eyes and steady gazes seem to look out of their gilded frames, right at me, as though to say, “She will get through this. You will get through this.” What do they know of my daughter and her struggles? What do they know of the ache in my heart?

I’m not sure I believe them, these women captured in paint on canvas, but, as I head back outside into the cold and start the walk back to see my daughter, I decide that I must believe them, that I must cling to the hope that, yes, some day my daughter will get better. That some day she will make it back home.

***

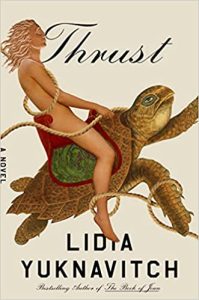

Have you ordered Thrust yet?

“Blistering and visionary . . . This is the author’s best yet.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

***

I send you supportive hugs virtually and hope your daughter is doing better. Mental illness is difficult to have, navigate and understand. Faith, hope and love…and listening to our loved ones is helpful, I have found. I’ve experienced it from both sides…i have depression and anxiety myself and o also have other family members who navigate their lives with more serious metal illness. We need more services for the community…not only financially but socially.

I hope you are doing okay. My thoughts are with you…and you may want to consider NAMI as a resource.