I turned 21 on June 3rd and on June 8th we got married under a Southern live oak. We walked hand in hand at the end of our wedding night in between everyone that molded us, moved us, reared us to this. A few months after, we left north. When we left Texas for Pennsylvania, I never felt more sure home wasn’t in the South. Home, I thought, would only exist when we found a place we wanted to return.

We were friends, until one night at a bookstore we layed bare our similar dreams, revealing somewhere underneath our desire to escape. Eventually, we grew dependent on the stability we garnered together, falling in love while creating some sort of base. To what? We didn’t know.

A friend in college once threw up from heartache. Her partner of two years broke up with her over the phone while we were in the girl’s communal bathroom. She hung up, grabbed her stomach, and ran into a stall crying. She hurled liquid and loud wails in an attempt to extract the pain. Withdraws from something her body knew and craved. I always imagined that’s how I’d miss you.

…

In Pennsylvania, we found our apartment while driving through Pittsburgh’s Shadyside. We drove down Elmer, a street over from Walnut, the one with all the shops and restaurants, when I spotted a third-floor apartment with a sunroom that stuck out like a balcony. I dreamt of that sunroom quietly while we explored the neighborhood.

Down Walnut, we took a right on Negley, and a left on Elsworth where we drove alongside mansions. I imagined the ease of old money. I imagined us in the large grey victorian home with the blue swing hanging on a red maple. I imagined, for the first time in a long time, with a twinge of confidence; a belief in us.

When you called later, and they told us the sunroom apartment would come available during the month we needed it, it did something to my psyche, promoted an exaggerated optimism that simply leaving was the end of it, the solution to our past. I never considered leaving as temporary, as only an element of healing.

When we moved in, we gave most of our money to the restaurants on Walnut: margarita pizza at Mercurios Gelato & Pizza, the crab rangoons at Asian Fusion, the frozaccino at Coffee Tree Roasters, or the chocolate chip cookies at Rite Aid, just before midnight. On the weekends we ventured a few streets down to the underground French cafe with our favorite French toast for breakfast at noon; yours covered in syrup and walnuts, mine with strawberries and whipped cream. We witnessed our first real snowfall, the kind that insulated the city. Middle-of-the-night snowfall in Pittsburgh, void of any footprints, conceals a city once deindustrialized and makes it new.

…

We lived together for three years in Texas. First, in my childhood home after my parent’s divorce. My mom moved to Virginia and let us stay there for cheap, and, in exchange, we prepared the house to sell. I hated living in my childhood home; I felt stuck inside something I both loved and wanted to forget. The power of that contrast consumed me and so you worked hard to finish.

Later we moved into one of your mom’s rental houses. We didn’t pay any rent and we were roommates with your Aunt Nancy. Aunt Nancy and her pet bird, aside from the time she hit on my dad or the time she told us she liked listening to us laugh in the middle of the night, was a pleasant roommate.

When she moved out, your brother moved in and brought his three-month-old son, Jax.

Unable to afford daycare, he sat Jax on our bed that first morning and nearly every morning after until we left. I kept my eyes shut working to resist the weight next to me until his little hand brushed my face. I opened my eyes to his double chin hanging over me. I took note of the few hairs on his gigantic head, admired the eyelashes on his big brown eyes as he studied me, and in unison, we smirked at each other.

I closed my eyes and sank deeper into the blanket as he tugged.

When you got the call about the job in Pittsburgh and I got my college acceptance, we never hesitated. Getting out was the plan. We talked about adopting Jax only once, after the first time CPS got involved, but I recoiled at the thought of motherhood and secretly resented the way I loved him. We left north the day after Christmas, couldn’t even wait for the year to end.

…

There’s a picture your mom took on that Christmas Eve of me, Jax, and Jax’s mom. I had just changed Jax’s diaper, the last diaper of his I’d change for a long time. We were sitting on your mom’s red couch, his mom to my right and Jax on my lap. Jax and I are looking at a book together and his mom is looking at the camera. This image only stood out to me after her overdose. I imagined the picture in my head, I saw her body fading and only Jax and I were left.

…

The time between Christmas and New Year’s always feels unresolved. I sat on the passenger side of the U-Haul observing the town slowly creep behind us. The parks and restaurants that once faded to the backdrop of our life now stood out. My brain took a mental picture of a place I knew so well, a place I ached to leave, but a place now embedded with Jax’s short life; a foggy sense of obligation.

…

We walked like kids into our new sunroom apartment, entering a space we earned. I held the paper with the list of things to check off, and we scanned each room for imperfections, and though there were many, we found none. I dropped the paper and, with proper third-floor etiquette, forced you to pretend-jump with me.

Holding both your hands,

“We have our own apartment!”

and synchronizing to my repetitive sumo squat, you repeated the words from my mouth, “we have our own apartment!”

It took a couple of days for us to feel the relief of being miles from Texas. Settling into our new calm illuminated the reality of our previous chaos, the space Jax remained.

…

In this safe place we stayed, hearing news from home, your mom is now fostering Jax; parent’s rights legally terminated.

At what point, if at all, does our shield, the place we created for rest (rest existing as both essential and temporary), become hiding?

…

We watched families with fear and admiration, as though we were expecting. We did the math in our heads; your mom will turn 72 the year Jax turns 16.

We sat at the summit of Schenley Park hill, looking out above everything and silent together. Our limbs fixed to the bench, staring ahead.

“He’s already attached to my mom,” you said, not looking at me.

I veered my head further away,

“you’re right, he’s already attached to your mom,”

I said, repeating the words from your mouth.

Our words floated but never impeded my imagination. From then on whatever we did: eating pho in Squirrel Hill, grabbing a seat on the city bus, drinking taro bubble tea, reading in the sunroom, sitting still in Shenley Park; I imagined it all as existing in double, now and with a child.

…

We flew to Dallas one weekend to see a close friend, piling with other friends in her tiny sedan, staying out at rooftop bars, and eating 2:00 am ice cream. We slept on an air mattress in the living room she and her roommates shared. The next day in her car she asked us about Jax, “so are you guys going to end up adopting him?” she looked at me and I looked away. “Well, I don’t know, he’s really attached to his grandma.” I recognized the lie because of the rehearsed switfness of my answer. I looked down at my hands, opening them to release what I was holding on to. She watched me in silence, then put the car in drive.

I never anticipated the labor of the coming year. But in the car I knew; I never told you, this is when I opened my hands to a possibility; that home lay synonymous to a feeling I harbored for a person.

…

I fell ill to some sort of virus on the eve of my December graduation, exactly two years after we set off northeast. This was pre-pandemic, and I walked the stage with body aches. I see this now as a sort of birth, a morphing, the physical equivalent of a hammer to a nail, the building of something.

***

Wondering what to read next?

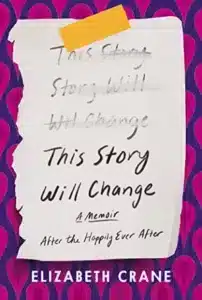

This is not your typical divorce memoir.

Elizabeth Crane’s marriage is ending after fifteen years. While the marriage wasn’t perfect, her husband’s announcement that it is over leaves her reeling, and this gem of a book is the result. Written with fierce grace, her book tells the story of the marriage, the beginning and the end, and gives the reader a glimpse into what comes next for Crane.

“Reading about another person’s pain should not be this enjoyable, but Crane’s writing, full of wit and charm, makes it so.”

—Kirkus (starred review)

***